Chapter 16

Deep Reinforcement Learning

"Reinforcement learning is the closest thing we have to a machine learning-based path to artificial general intelligence." — Richard Sutton

Chapter 16 of DLVR provides a comprehensive exploration of Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL), a powerful paradigm that combines reinforcement learning with deep learning to solve complex decision-making problems. The chapter begins by introducing the core concepts of reinforcement learning, including agents, environments, actions, rewards, and policies, within the framework of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). It delves into the exploration-exploitation trade-off, value functions, and the role of policies in guiding an agent's actions. The chapter then covers key DRL algorithms, starting with Deep Q-Networks (DQN), which use deep neural networks to estimate action-value functions, followed by policy gradient methods like REINFORCE that directly optimize the policy. The discussion extends to actor-critic methods, which combine the strengths of policy gradients and value-based methods for stable learning. Advanced topics such as multi-agent reinforcement learning, hierarchical RL, and model-based RL are also explored, emphasizing their potential to tackle complex, real-world problems. Throughout, practical implementation guidance is provided with Rust-based examples using tch-rs and burn, enabling readers to build, train, and evaluate DRL agents on various tasks, from simple grid worlds to more challenging environments like LunarLander.

16.1. Introduction to Deep Reinforcement Learning

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) represents a significant expansion of the capabilities of traditional Reinforcement Learning (RL) by integrating deep learning techniques into the RL framework. While traditional RL centers on the interaction between an agent and its environment—where the agent learns through trial and error to take actions that maximize a cumulative reward—it often relies on tabular methods or simple function approximations. These approaches work well in environments with relatively small state and action spaces, such as classic control problems like grid-worlds or cart-pole balancing, where the agent can feasibly explore and learn the value of each state-action pair.

The challenge for traditional RL arises in high-dimensional state spaces encountered in fields like robotics, computer vision, and autonomous driving. Here, the state of the environment might be represented by raw sensory data such as images, video frames, or lidar scans, leading to a vast number of potential states. In such complex settings, relying on tabular methods or basic function approximators is impractical due to the explosive growth in state space complexity. This is where DRL proves its value, extending the reach of RL into domains where deep learning can effectively handle complex, high-dimensional inputs.

Figure 1: Taxonomy of DRL models.

The taxonomy of DRL provides a structured way to categorize the diverse techniques used within the field. These categories include value-based methods, policy-based methods, actor-critic methods, model-free and model-based approaches, each serving different needs depending on the nature of the environment and the problem being addressed.

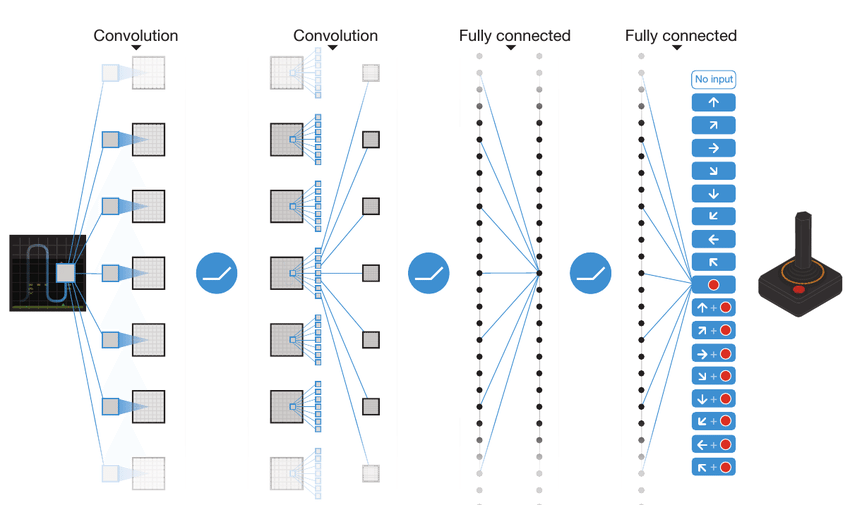

Value-Based Methods focus on estimating the action-value function $Q(s, a)$, which represents the expected cumulative reward for taking action aaa in state sss and following a given policy thereafter. The goal is to derive an optimal policy indirectly by learning the best actions through these value estimates. A prominent example is the Deep Q-Network (DQN), where a deep neural network (DNN) approximates the Q-function. DQN is effective for environments where the action space is discrete, such as playing Atari games. Value-based methods excel in environments where a clear mapping between states and action values can be learned and exploited.

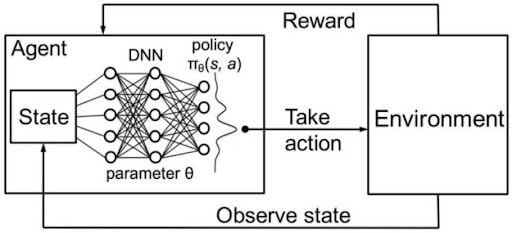

Policy-Based Methods take a different approach by directly learning a policy $\pi_{\theta}(a \mid s)$, parameterized by $\theta$, which outputs the probability distribution over actions given a state. This approach is particularly useful for continuous action spaces, where the policy directly determines the agent's actions, such as controlling the steering of an autonomous vehicle or adjusting the joint angles of a robotic arm. Policy Gradient (PG) methods, such as REINFORCE, update the policy parameters using gradient ascent to maximize expected rewards. These methods are well-suited for tasks where learning a direct mapping from states to actions is more efficient than first estimating value functions.

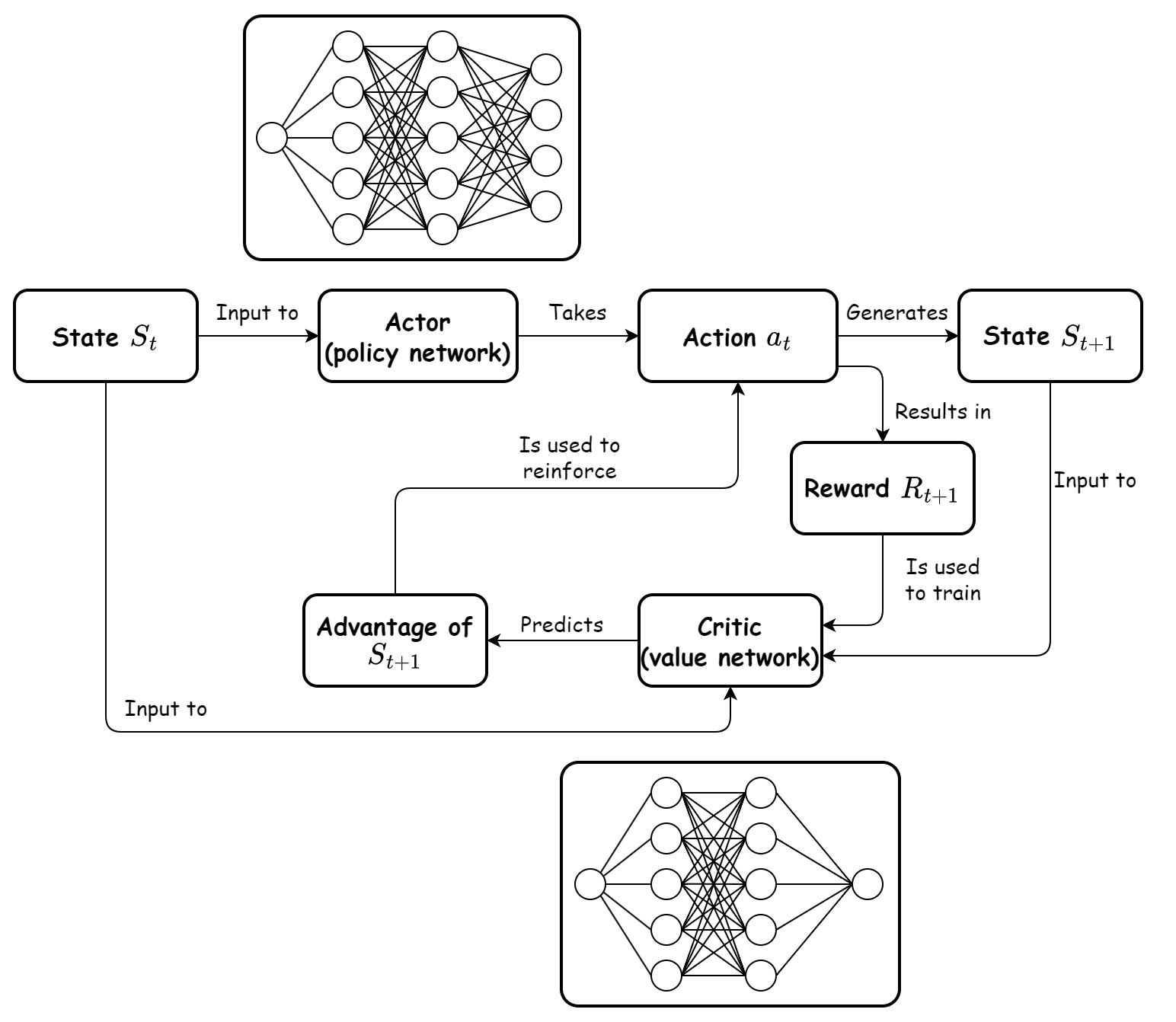

Actor-Critic Methods combine the advantages of value-based and policy-based approaches by learning both a policy (the actor) and a value function (the critic). The actor chooses actions based on the current policy, while the critic evaluates the actions by estimating the value function, providing feedback to the actor to improve the policy. The Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) methods are popular examples in this category. Actor-critic methods offer improved stability over pure policy gradient methods by using the critic to reduce the variance of policy updates. These methods are commonly used in complex control problems like robotic locomotion and multi-agent environments, where agents must learn nuanced control strategies.

Model-Free DRL focuses on learning policies and value functions directly through interactions with the environment, without trying to learn a model of the environment’s dynamics. This approach is suitable for situations where the environment is complex and unpredictable, and where it is easier to learn a policy directly rather than approximating the environment's transition dynamics. Methods like DQN, A2C, and PPO fall into this category. Model-free methods are widely used in scenarios like game AI and robotic manipulation because they can adapt to complex dynamics purely through experience.

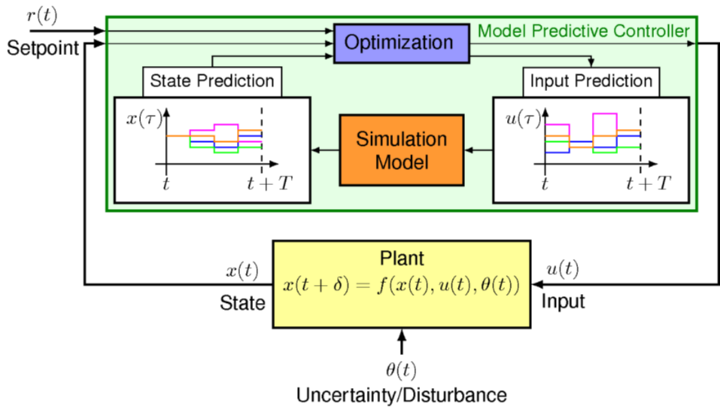

Model-Based DRL, on the other hand, involves learning an approximation of the environment’s transition dynamics and using this learned model for planning and policy improvement. By learning a transition model $\hat{P}(s' \mid s, a)$ and a reward model $\hat{R}(s, a)$, the agent can simulate future states and rewards, allowing for more sample-efficient learning. This approach can significantly reduce the number of real-world interactions needed, making it particularly valuable in applications where interactions are costly, such as robotics or healthcare. Model Predictive Control (MPC) is a popular technique in this category, where the agent plans a sequence of actions using the learned model to optimize future rewards.

Meta-Learning in DRL is a more recent addition to the taxonomy, focusing on agents that can learn how to learn. Instead of optimizing a single policy, meta-RL trains agents across a range of tasks, enabling them to quickly adapt to new tasks with minimal additional training. This is achieved by optimizing initial policy parameters that are amenable to rapid fine-tuning when exposed to a new task. Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) is a well-known technique for meta-RL. This approach is particularly useful in environments where tasks change frequently, such as robotic manipulation with varying objects or adaptive game-playing agents that face different opponents.

Exploration Techniques in DRL are critical due to the challenge of balancing exploration (trying new actions to discover rewards) and exploitation (choosing actions that are known to yield high rewards). Advanced exploration strategies like curiosity-driven exploration and entropy regularization encourage agents to explore more thoroughly. These techniques ensure that agents do not get stuck in local optima, especially in large or sparse environments where rewards are infrequent. For example, in robotic exploration, curiosity-driven agents can explore uncharted areas more effectively than those using simple random exploration strategies.

Transfer Learning in DRL extends the utility of trained models by reusing knowledge from one environment to accelerate learning in another, related environment. This is particularly beneficial in domains where collecting training data is expensive or time-consuming. For instance, a model trained on simulated robotic tasks can be fine-tuned in a real-world environment, leveraging the knowledge from the simulation to speed up learning in reality. Transfer learning enables cross-domain adaptation, such as applying knowledge from a driving simulator to improve performance in real-world autonomous vehicle scenarios.

This taxonomy highlights the expansive scope of Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) compared to traditional Reinforcement Learning (RL). While RL lays the groundwork for interaction-based learning through trial and error, DRL significantly broadens this scope through the integration of deep neural networks and sophisticated learning strategies. The ability of DRL to handle high-dimensional inputs, complex action spaces, and dynamic, multi-agent environments makes it indispensable for modern AI applications. With its structured approach to different challenges—whether through value-based methods like DQN, policy-based methods like REINFORCE, or more advanced strategies like model-based and meta-learning—DRL provides a versatile and powerful framework for building adaptive agents capable of solving real-world problems. This versatility has made DRL a cornerstone of robotics, autonomous systems, game AI, financial trading, and healthcare, driving innovation across industries where intelligent decision-making is key.

DRL utilizes deep neural networks (DNNs) to approximate crucial functions in the RL framework, such as value functions $V^{\pi}(s)$, action-value functions $Q^{\pi}(s, a)$, and policies $\pi_{\theta}(a \mid s)$. This integration allows DRL to represent intricate mappings between states and actions, making it possible for agents to learn directly from continuous and unstructured data, like images. For instance, in the context of Atari game environments, an agent can use a convolutional neural network (CNN) to process pixel data from the game screen, producing a policy for selecting actions. This kind of capability is beyond the scope of standard RL methods, which cannot handle the sheer volume of possible states represented by pixel configurations.

One of the most notable advantages of DRL is its ability to automatically learn latent representations from raw data such as images, audio, or text. Through end-to-end learning, DRL can discover the most relevant features for decision-making directly from the data, removing the need for extensive manual feature engineering often required in traditional RL. This feature makes DRL particularly suitable for applications like robotic vision, where an agent must interpret visual data to interact effectively with its environment, and in natural language processing, where agents use text data to make informed decisions or hold conversations.

DRL also extends the range of behaviors that agents can learn, allowing them to tackle more complex and partially observable environments. Traditional methods like Q-learning or SARSA are effective in fully observable environments but face difficulties when the agent does not have direct access to the complete state information. DRL addresses these challenges using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformers, which can maintain a memory of past observations, helping agents to make decisions based on sequences of events. This ability to process temporal information is crucial in strategy games, where agents must infer the opponent's strategy over time, and in robotic navigation, where the environment might change dynamically and require adaptive decision-making.

Beyond perception, DRL facilitates the use of advanced learning algorithms, such as actor-critic methods and policy gradients, which require approximating both value functions and policies. In many continuous control tasks, like those found in robotics or autonomous vehicles, the ability of DRL to approximate these functions using deep networks allows for fine-grained control and the handling of continuous action spaces. This flexibility enables DRL agents to make precise adjustments in physical environments, optimizing complex behaviors that are critical in robotic manipulation or driving strategies.

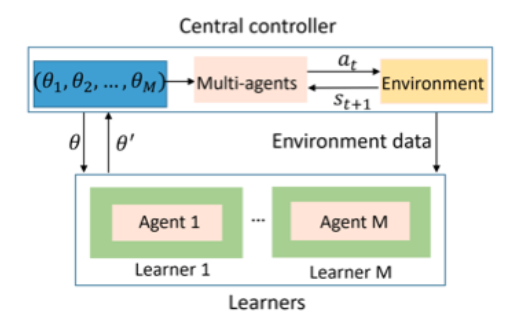

DRL's scope is further expanded in multi-agent environments, where multiple agents must interact within a shared space, either collaboratively or competitively. Deep networks' ability to capture and process complex state information allows DRL agents to learn coordinated behaviors or strategic interactions, adapting their policies in response to other agents' actions. This capability is especially important in real-time strategy games or multi-robot systems, where agents must continuously adapt their strategies based on the evolving behavior of teammates or opponents.

In summary, while traditional RL remains a powerful tool for learning through interactions with environments, Deep Reinforcement Learning significantly expands its applicability by incorporating deep learning's representational power. This enables agents to learn in high-dimensional, unstructured, and dynamic environments, bridging the gap between theoretical RL concepts and real-world challenges. DRL is now essential in diverse applications, including robotics, autonomous navigation, finance, healthcare, and entertainment, where the ability to process complex data and learn sophisticated behaviors makes it a cornerstone of modern AI research and practical implementations.

At the core of reinforcement learning lies the Markov Decision Process (MDP), a formal framework for modeling decision-making problems. An MDP is defined by the tuple $(S, A, P, R, \gamma)$, where:

$S$: A set of states representing the possible situations in which an agent can find itself.

$A$: A set of actions available to the agent.

$P(s' \mid s, a)$: The transition probability function, representing the probability of transitioning to state $s'$ after taking action aaa in state sss.

$R(s, a)$: The reward function, defining the reward received when the agent takes action aaa in state sss.

$\gamma \in [0, 1]$: The discount factor, which determines the importance of future rewards relative to immediate rewards.

The objective in an MDP is to learn a policy $\pi(a \mid s)$ that maximizes the expected cumulative discounted reward:

$$ \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t R(s_t, a_t) \mid \pi\right], $$

where $s_t$ and $a_t$ denote the state and action at time $t$. A policy can be deterministic $\pi(s) = a$ or stochastic $\pi(a \mid s)$ gives the probability of selecting action $a$ given state $s$). The value function $V^\pi(s)$ represents the expected return starting from state $s$ under policy $\pi$, and the action-value function $Q^\pi(s, a)$ represents the expected return for taking action $a$ in state $s$ and following $\pi$ thereafter. These functions are fundamental for evaluating the quality of policies.

One of the central challenges in reinforcement learning is the exploration-exploitation trade-off. The agent must explore to discover new strategies that might yield higher rewards, but it must also exploit existing knowledge to maximize rewards based on its current understanding. This trade-off is crucial for learning optimal policies, and balancing it effectively is a key aspect of algorithms like Q-learning and Deep Q-Networks (DQN). The exploration can be managed using strategies like $\epsilon$-greedy policies, where the agent chooses a random action with probability $\epsilon$ and the action that maximizes $Q$ values with probability $1 - \epsilon$.

In Q-learning, the Q-value update rule is defined as:

$$ Q(s, a) \leftarrow Q(s, a) + \alpha \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a') - Q(s, a) \right], $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, $s'$ is the next state after taking action $a$, and $a'$ is the action that maximizes the Q-value in the next state. This update aims to reduce the temporal difference error, which is the discrepancy between the current Q-value and the value obtained from a one-step lookahead.

Deep reinforcement learning has shown significant potential across various industries where adaptive decision-making is crucial. In healthcare, RL models can optimize personalized treatment plans, adjusting recommendations based on patient responses over time. In autonomous driving, DRL is used for real-time navigation, where the agent learns to control a vehicle by interacting with its environment, making decisions to avoid obstacles and reach destinations. In financial trading, RL agents balance the trade-off between exploration (trying new trading strategies) and exploitation (using known profitable strategies) to optimize portfolios and maximize returns. These applications rely heavily on the ability of DRL to generalize from training environments to real-world scenarios, which makes pre-training and fine-tuning critical for deployment.

This code implements a Q-learning algorithm for a 5x5 grid world environment, where the agent navigates the grid to reach a goal state while avoiding penalties for each step. The environment, modeled as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), consists of states representing grid cells and actions to move up, down, left, or right. Using a Q-table, the agent learns the optimal policy by iteratively updating state-action values through trial and error. Each episode begins with the agent in a random state, exploring the grid using an epsilon-greedy strategy to balance exploration and exploitation. At every step, the agent updates the Q-value for its state-action pair based on the observed reward and the maximum Q-value of the next state, guided by the learning rate and discount factor. After each episode, the grid is visualized with the optimal action for each state based on the current Q-table, while the total reward accumulated during the episode is printed to monitor the agent's learning progress.

[dependencies]

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

use rand::Rng;

use plotters::prelude::*;

const NUM_STATES: usize = 25; // Number of states in a 5x5 grid world

const NUM_ACTIONS: usize = 4; // Number of actions: Up, Down, Left, Right

const GRID_SIZE: usize = 5; // Size of the grid (5x5)

fn main() {

let mut q_table = vec![vec![0.0; NUM_ACTIONS]; NUM_STATES]; // Initialize Q-table

let alpha = 0.1; // Learning rate

let gamma = 0.9; // Discount factor

let epsilon = 0.1; // Exploration rate for epsilon-greedy policy

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for episode in 0..1000 { // Loop over 1000 episodes

println!("Starting episode {}", episode + 1); // Print the current episode number

let mut state = rng.gen_range(0..NUM_STATES); // Initialize a random starting state

let mut total_reward = 0.0; // Track total reward for the episode

while !is_terminal(state) { // Continue until a terminal state is reached

// Select an action using epsilon-greedy policy

let action = if rng.gen::<f64>() < epsilon {

rng.gen_range(0..NUM_ACTIONS) // Random action (explore)

} else {

q_table[state]

.iter()

.cloned()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(&b.1).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap() // Best action (exploit)

};

// Take the action and observe the next state and reward

let next_state = take_action(state, action);

let reward = get_reward(state, action);

// Accumulate the reward

total_reward += reward;

// Perform the Q-learning update

let best_next_action = q_table[next_state]

.iter()

.cloned()

.fold(f64::NEG_INFINITY, f64::max); // Maximum Q-value of the next state

q_table[state][action] += alpha

* (reward + gamma * best_next_action - q_table[state][action]); // Update Q-value

state = next_state; // Transition to the next state

}

// Print the total reward for the episode

println!("Episode {}: Total Reward = {:.2}", episode + 1, total_reward);

// Visualize the Q-table after each episode

visualize_grid(&q_table, episode);

}

}

/// Visualizes the grid using plotters and saves the plot for each episode

fn visualize_grid(q_table: &Vec<Vec<f64>>, episode: usize) {

// Generate the file name for the current episode

let file_name = format!("q_learning_episode_{}.png", episode);

// Create a drawing area for the plot

let root_area = BitMapBackend::new(&file_name, (600, 600)).into_drawing_area();

root_area.fill(&WHITE).unwrap();

// Create a chart builder for the grid

let mut chart = ChartBuilder::on(&root_area)

.margin(10)

.x_label_area_size(20)

.y_label_area_size(20)

.build_cartesian_2d(0..GRID_SIZE as i32, 0..GRID_SIZE as i32)

.unwrap();

chart.configure_mesh().draw().unwrap();

// Draw the grid with colors representing the best actions

for state in 0..NUM_STATES {

let (x, y) = state_to_xy(state);

// Find the best action for the current state

let best_action = q_table[state]

.iter()

.cloned()

.enumerate()

.max_by(|a, b| a.1.partial_cmp(&b.1).unwrap())

.map(|(idx, _)| idx)

.unwrap();

// Assign colors to actions

let color = match best_action {

0 => &RED, // Up

1 => &GREEN, // Down

2 => &BLUE, // Left

3 => &YELLOW, // Right

_ => &BLACK,

};

// Draw the rectangle representing the state

chart

.draw_series(std::iter::once(Rectangle::new(

[(x, y), (x + 1, y + 1)],

color.filled(),

)))

.unwrap();

}

// Save the plot

root_area.present().unwrap();

}

/// Converts a state index to x, y coordinates in the grid

fn state_to_xy(state: usize) -> (i32, i32) {

let x = state % GRID_SIZE;

let y = GRID_SIZE - 1 - (state / GRID_SIZE);

(x as i32, y as i32)

}

/// Checks if the given state is a terminal state

fn is_terminal(state: usize) -> bool {

state == 24 // Define terminal state (e.g., state 24 is the goal)

}

/// Simulates the agent's action and returns the next state

fn take_action(state: usize, action: usize) -> usize {

let (x, y) = state_to_xy(state);

match action {

0 if y < GRID_SIZE as i32 - 1 => state - GRID_SIZE, // Move Up

1 if y > 0 => state + GRID_SIZE, // Move Down

2 if x > 0 => state - 1, // Move Left

3 if x < GRID_SIZE as i32 - 1 => state + 1, // Move Right

_ => state, // Invalid action, no movement

}

}

/// Returns the reward for the given state and action

fn get_reward(state: usize, _action: usize) -> f64 {

if state == 24 {

10.0 // Reward for reaching the goal state

} else {

-1.0 // Penalty for each step

}

}

The code initializes a Q-table with dimensions corresponding to the number of states (25 for a 5x5 grid) and possible actions (4 directions). It uses Q-learning to update this table, aiming to approximate the optimal value function that predicts future rewards for taking specific actions. For each episode, the agent starts in a random state and selects actions using an epsilon-greedy policy: with a small probability ($\epsilon$), it explores random actions to avoid local optima, while most of the time, it exploits the best-known actions based on current Q-values. When an action is taken, the agent transitions to a new state, receives a reward (positive if reaching the goal, negative for other steps), and updates the Q-value using the Q-learning update rule. This update incorporates the immediate reward and the estimated value of the future state, weighted by the learning rate ($\alpha$) and discount factor ($\gamma$).

To visualize the agent's learning progress, the visualize_grid function uses the plotters crate to render the grid environment as a PNG image after each episode. It draws each state as a colored square, where the color indicates the action with the highest Q-value (e.g., red for "up" or green for "down"). This graphical representation helps observe how the agent's policy evolves as it learns to navigate towards the goal. Functions like is_terminal, take_action, and get_reward define the environment's dynamics, such as when the episode ends (goal state), how actions move the agent through the grid, and the reward structure. By producing visual outputs, the code provides an intuitive understanding of the learning process, showing how the agent's behavior adapts over time to find the most efficient path through the grid world.

The total reward for each episode provides a measure of how efficiently the agent navigates the grid. Initially, the reward is low as the agent explores and learns the environment, often taking suboptimal paths. Over time, as the Q-table updates and the agent identifies the optimal policy, the total reward increases, reflecting shorter paths to the goal. The visualizations reveal the agent's learned policy after each episode, with colors indicating the best action for each state. These visuals help track how the agent's behavior evolves, starting from random actions and gradually converging to a strategy that maximizes rewards. By observing the rewards and policy maps, you can assess the learning progress and verify that the agent achieves its goal effectively.

This section has laid out a comprehensive introduction to deep reinforcement learning, connecting formal MDP theory with practical algorithms like Q-learning. Using Rust, we can build scalable models that leverage deep neural networks for approximating value functions and policies, enabling the agent to handle complex and high-dimensional tasks. Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), and Actor-Critic methods extend these principles, combining neural networks with reinforcement learning to solve problems in diverse domains, from robotic control and game playing to supply chain optimization and energy management, making DRL a cornerstone of modern AI research and industry innovation.

16.2. Deep Q-Networks (DQN)

Deep Q-Networks (DQN) represent a significant advancement in reinforcement learning by using deep neural networks (DNNs) to approximate the Q-value function, enabling agents to operate effectively in environments with high-dimensional state spaces. In traditional Q-learning, the agent maintains a Q-table that stores estimates of action values for every state-action pair. This approach becomes infeasible in environments where the state space is large, such as in image-based environments encountered in video games or robotics. The sheer number of possible states, such as all possible configurations of pixels in an image, makes storing and updating a Q-table impractical. DQN addresses this by using a neural network, termed the Q-network, to approximate the function $Q(s, a; \theta)$, where $s$ represents the state, $a$ represents the action, and $\theta$ denotes the parameters of the network (the weights). This approximation allows DQN to generalize across similar states, making it capable of handling continuous or large discrete state spaces, overcoming the scalability issues of tabular methods.

Figure 2: Example of a Deep Q network architecture (eq. Gaming).

The primary objective of Q-learning is to learn an optimal action-value function $Q^*(s, a)$, which represents the expected cumulative reward (or return) when starting from state sss, taking action $a$, and subsequently following an optimal policy. The Bellman optimality equation defines the relationship between optimal Q-values as follows:

$$ Q^*(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_{s'} \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \max_{a'} Q^*(s', a') \mid s, a \right], $$

where $s'$ is the next state reached after taking action $a$ in state $s$, $R(s, a)$ is the immediate reward received for that action, and $\gamma \in [0, 1]$ is the discount factor that determines the importance of future rewards. A higher value of $\gamma$ places greater emphasis on long-term rewards, while a lower value focuses more on immediate rewards. In DQN, the Q-network approximates $Q(s, a; \theta)$ using gradient descent to minimize the temporal difference (TD) error, which measures the discrepancy between the predicted Q-values and the target Q-values computed using the Bellman equation. The loss function for training the Q-network is defined as:

$$ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{(s, a, r, s') \sim \mathcal{D}} \left[ \left( r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta^-) - Q(s, a; \theta) \right)^2 \right], $$

where $\mathcal{D}$ is the replay buffer storing past experiences as tuples $(s, a, r, s')$, and $\theta^-$ represents the parameters of a target network that is a delayed copy of the Q-network. The loss function aims to minimize the squared difference between the target Q-value $y$ (computed using the target network) and the Q-network's prediction, thereby iteratively adjusting $\theta$ to improve the network’s accuracy.

To stabilize training and address the problem of correlated experiences, DQN introduces experience replay. This involves maintaining a replay buffer $\mathcal{D}$ that stores a fixed number of the agent’s past experiences. Instead of updating the Q-network immediately after every action, the agent samples mini-batches of experiences from this buffer to compute the loss. This approach breaks the correlation between consecutive experiences, ensuring that the learning process is more stable and less prone to the oscillations that arise from highly correlated updates. By learning from a broader distribution of past interactions, the Q-network converges more reliably to an optimal policy.

Another essential mechanism is the use of target networks to provide stable targets for the Q-learning updates. Instead of using the same Q-network to compute both the predicted and target Q-values, DQN maintains a target Q-network with parameters $\theta^-$, which is updated less frequently. Typically, the parameters of the target network are set to the Q-network's parameters $\theta$ after a fixed number of iterations, creating a more stable target for computing the TD error. The target value is computed as:

$$ y = r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta^-), $$

where $y$ is the target Q-value used to update the Q-network. By using a delayed target network, the DQN reduces the likelihood of divergence during training, preventing rapid fluctuations in target values that could destabilize the learning process.

A significant challenge in DQN is overestimation bias, which occurs when the Q-network tends to overestimate the value of certain actions. This bias arises because the same network is used to select the action (via $\max_{a'}$) and to evaluate it. Over time, this can lead the agent to develop suboptimal policies, as it might favor actions that are wrongly perceived as valuable. Double DQN (DDQN) addresses this issue by decoupling the action selection and action evaluation steps. In DDQN, the Q-network is used to select the action, but the target network is used to evaluate the action’s value. The update rule for DDQN is:

$$ y = r + \gamma Q(s', \arg\max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta); \theta^-), $$

where $\arg\max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta)$ selects the action using the Q-network, but the value is computed using the target network $\theta^-$. This approach reduces the overestimation bias, resulting in more accurate action-value estimates and improved policy stability. The reduction of bias through this technique is critical in environments with noisy rewards or complex dynamics, where overestimation can otherwise lead to degraded performance.

Deep Q-Networks have found applications across a variety of fields where making decisions in complex, uncertain environments is critical. One of the most well-known successes of DQN is in the domain of game AI, where DQN-based agents have been trained to play Atari games directly from raw pixel data, achieving superhuman performance in several cases. By learning from the game environment, these agents can map images of the game screen to actions, such as moving a paddle in Breakout or navigating through obstacles in Space Invaders, showcasing the ability of DQN to handle high-dimensional inputs.

In autonomous driving, DQNs are used to train agents for tasks like lane navigation, collision avoidance, and parking. The agent interacts with a simulated driving environment, using sensor data such as camera images or lidar scans to determine optimal driving strategies. The DQN learns to map these high-dimensional sensory inputs to actions that maximize safety and efficiency, such as steering or accelerating, providing a foundation for more complex driving behaviors.

Robotic control is another domain where DQN has been applied effectively. In tasks like robotic arm manipulation or path planning, the agent learns to control actuators to achieve precise movements, such as picking up objects or avoiding obstacles. By interacting with a physical or simulated environment, the DQN learns a policy that maximizes task-specific rewards, like minimizing energy consumption while reaching a target position. This is particularly valuable in manufacturing and logistics, where robots must handle a wide range of objects and environments.

In the field of finance and trading, DQNs can be employed to build algorithmic trading agents that learn to execute trades based on market data. The agent interacts with a simulated stock market, adjusting its trading strategy to maximize returns while minimizing risks. The DQN learns patterns from historical price data and market indicators, making buy, sell, or hold decisions based on potential future trends. This application of DQN is especially relevant in high-frequency trading, where the agent must quickly adapt to changes in market conditions.

In healthcare, DQNs have been explored for personalized treatment recommendations, where the agent suggests actions based on a patient’s evolving medical condition to optimize long-term health outcomes. By learning to balance immediate rewards (e.g., symptom relief) and long-term outcomes (e.g., reduced disease progression), DQNs can aid in designing personalized drug dosages or lifestyle intervention plans. This approach is particularly useful for chronic disease management, where patient data is continuously monitored, and treatment plans must be adapted over time.

Through these applications, DQNs have demonstrated their capability to generalize across complex environments and learn sophisticated strategies directly from raw data, making them a powerful tool in the arsenal of modern AI techniques. By combining deep learning with reinforcement learning, DQN offers a scalable solution for decision-making problems that were previously intractable with traditional methods, driving innovation across numerous industries.

Implementing DQN requires careful tuning of hyperparameters such as learning rate ($\alpha$), discount factor ($\gamma$), replay buffer size, and the frequency of target network updates. The exploration-exploitation balance is managed using strategies like the epsilon-greedy policy, where the agent selects a random action with probability $\epsilon$ and the action with the highest Q-value otherwise. Decaying $\epsilon$ over time allows the agent to explore initially and focus on exploitation as it gains more experience.

The training process is computationally intensive, especially when dealing with environments with high-dimensional inputs like images. Using GPU acceleration with libraries like tch-rs or candle in Rust can significantly speed up training, allowing the Q-network to process large batches of data efficiently. Moreover, techniques like prioritized experience replay, where experiences with higher TD errors are sampled more frequently, can further enhance learning efficiency by focusing updates on the most informative transitions.

Now let see a DRL implementation using tch-rs. The presented model utilizes a Double DQN architecture, combined with a prioritized experience replay mechanism, to solve the CartPole environment. The Q-Network, a neural network designed using the tch-rs crate, takes the current state of the environment as input and outputs Q-values for possible actions. The network consists of three fully connected layers: the first layer maps the state dimensions to 128 neurons, the second reduces it to 64, and the final layer outputs Q-values corresponding to the action space. ReLU activation functions are applied after the first two layers to introduce non-linearity. This architecture enables the agent to approximate the optimal Q-function effectively.

[dependencies]

plotters = "0.3.7"

rand = "0.8.5"

tch = "0.12.0"

use rand::thread_rng;

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor, Kind};

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use rand::Rng;

// Define the Q-Network

fn q_network(vs: &nn::Path, state_dim: i64, action_dim: i64) -> impl Module {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer1", state_dim, 128, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer2", 128, 64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "output", 64, action_dim, Default::default()))

}

// CartPole Environment

struct CartPole {

state: Vec<f64>,

step_count: usize,

max_steps: usize,

gravity: f64,

mass_cart: f64,

mass_pole: f64,

pole_length: f64,

force_mag: f64,

dt: f64,

}

impl CartPole {

fn new() -> Self {

Self {

state: vec![0.0; 4], // [x, x_dot, theta, theta_dot]

step_count: 0,

max_steps: 500,

gravity: 9.8,

mass_cart: 1.0,

mass_pole: 0.1,

pole_length: 0.5,

force_mag: 10.0,

dt: 0.02,

}

}

fn reset(&mut self) -> Vec<f64> {

self.step_count = 0;

// Initialize with small random values

self.state = vec![

thread_rng().gen::<f64>() * 0.1 - 0.05, // x

thread_rng().gen::<f64>() * 0.1 - 0.05, // x_dot

thread_rng().gen::<f64>() * 0.1 - 0.05, // theta

thread_rng().gen::<f64>() * 0.1 - 0.05, // theta_dot

];

self.state.clone()

}

fn step(&mut self, action: i64) -> (Vec<f64>, f64, bool) {

self.step_count += 1;

let force = if action == 1 { self.force_mag } else { -self.force_mag };

let x = self.state[0];

let x_dot = self.state[1];

let theta = self.state[2];

let theta_dot = self.state[3];

let total_mass = self.mass_cart + self.mass_pole;

let pole_mass_length = self.mass_pole * self.pole_length;

// Physics calculations

let temp = (force + pole_mass_length * theta_dot.powi(2) * theta.sin()) / total_mass;

let theta_acc = (self.gravity * theta.sin() - temp * theta.cos())

/ (self.pole_length * (4.0 / 3.0 - self.mass_pole * theta.cos().powi(2) / total_mass));

let x_acc = temp - pole_mass_length * theta_acc * theta.cos() / total_mass;

// Update state using Euler integration

self.state[0] = x + x_dot * self.dt;

self.state[1] = x_dot + x_acc * self.dt;

self.state[2] = theta + theta_dot * self.dt;

self.state[3] = theta_dot + theta_acc * self.dt;

// Check if episode is done

let done = self.state[0].abs() > 2.4

|| self.state[2].abs() > 0.209 // 12 degrees

|| self.step_count >= self.max_steps;

let reward = if !done { 1.0 } else { 0.0 };

(self.state.clone(), reward, done)

}

}

// Prioritized Experience Replay Buffer

struct PrioritizedReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque<(Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool, f64)>, // Added priority

capacity: usize,

alpha: f64, // Priority exponent

beta: f64, // Importance sampling weight

epsilon: f64, // Small constant to avoid zero probability

}

impl PrioritizedReplayBuffer {

fn new(capacity: usize) -> Self {

PrioritizedReplayBuffer {

buffer: VecDeque::with_capacity(capacity),

capacity,

alpha: 0.6,

beta: 0.4,

epsilon: 1e-6,

}

}

fn add(&mut self, experience: (Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool), error: f64) {

let priority = (error.abs() + self.epsilon).powf(self.alpha);

if self.buffer.len() >= self.capacity {

self.buffer.pop_front();

}

self.buffer.push_back((

experience.0,

experience.1,

experience.2,

experience.3,

experience.4,

priority,

));

}

fn sample(&self, batch_size: usize) -> (Vec<(Tensor, i64, f64, Tensor, bool)>, Vec<f64>) {

let total_priority: f64 = self.buffer.iter().map(|(_, _, _, _, _, p)| p).sum();

let _rng = thread_rng();

let samples: Vec<_> = (0..batch_size)

.map(|_| {

let p = rand::random::<f64>() * total_priority;

let mut acc = 0.0;

let mut idx = 0;

for (i, (_, _, _, _, _, priority)) in self.buffer.iter().enumerate() {

acc += priority;

if acc > p {

idx = i;

break;

}

}

idx

})

.collect();

let max_weight = (self.buffer.len() as f64 * self.buffer[0].5 / total_priority)

.powf(-self.beta);

let weights: Vec<f64> = samples

.iter()

.map(|&idx| {

let p = self.buffer[idx].5 / total_priority;

(self.buffer.len() as f64 * p).powf(-self.beta) / max_weight

})

.collect();

let experiences: Vec<_> = samples

.iter()

.map(|&idx| {

let (s, a, r, ns, d, _) = &self.buffer[idx];

(s.shallow_clone(), *a, *r, ns.shallow_clone(), *d)

})

.collect();

(experiences, weights)

}

}

// Train Double DQN Model

fn train_double_dqn() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let state_dim = 4;

let action_dim = 2;

let q_net = q_network(&vs.root(), state_dim, action_dim);

let mut target_vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let target_net = q_network(&target_vs.root(), state_dim, action_dim);

target_vs.copy(&vs).unwrap();

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3).unwrap();

let mut replay_buffer = PrioritizedReplayBuffer::new(100_000);

let mut env = CartPole::new();

let epsilon_start = 1.0;

let epsilon_end = 0.01;

let epsilon_decay = 0.995;

let mut epsilon = epsilon_start;

let gamma = 0.99;

let batch_size = 64;

let target_update_interval = 10;

for episode in 0..1000 {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

let mut done = false;

while !done {

let state_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&state)

.to_device(device)

.to_kind(Kind::Float);

// Epsilon-greedy action selection

let action = if rand::random::<f64>() < epsilon {

rand::thread_rng().gen_range(0..action_dim)

} else {

let selected_action = q_net

.forward(&state_tensor.unsqueeze(0))

.argmax(-1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

selected_action

};

let (next_state, reward, is_done) = env.step(action);

total_reward += reward;

done = is_done;

let next_state_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&next_state)

.to_device(device)

.to_kind(Kind::Float);

let experience = (

state_tensor.shallow_clone(),

action,

reward,

next_state_tensor.shallow_clone(),

done,

);

// Calculate initial error for prioritized replay

let current_q = q_net

.forward(&state_tensor.unsqueeze(0))

.gather(1, &Tensor::of_slice(&[action]).to_device(device).unsqueeze(0), false)

.squeeze();

let next_q = target_net

.forward(&next_state_tensor.unsqueeze(0))

.max_dim(1, false)

.0;

let target_q = Tensor::of_slice(&[reward + (1.0 - done as i64 as f64) * gamma])

.to_device(device)

* next_q;

let error = (current_q - target_q).abs().double_value(&[]);

replay_buffer.add(experience, error);

if replay_buffer.buffer.len() >= batch_size {

let (batch, weights) = replay_buffer.sample(batch_size);

let weights_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&weights).to_device(device);

let states: Vec<_> = batch.iter().map(|(s, _, _, _, _)| s.unsqueeze(0)).collect();

let actions: Vec<_> = batch.iter().map(|(_, a, _, _, _)| *a).collect();

let rewards: Vec<_> = batch.iter().map(|(_, _, r, _, _)| *r).collect();

let next_states: Vec<_> = batch.iter().map(|(_, _, _, ns, _)| ns.unsqueeze(0)).collect();

let dones: Vec<_> = batch.iter().map(|(_, _, _, _, d)| *d as i64 as f64).collect();

let states = Tensor::cat(&states, 0);

let actions = Tensor::of_slice(&actions).to(device);

let rewards = Tensor::of_slice(&rewards).to(device);

let next_states = Tensor::cat(&next_states, 0);

let dones = Tensor::of_slice(&dones).to(device);

// Double DQN

let next_actions = q_net.forward(&next_states).argmax(-1, false);

let next_q_values = target_net

.forward(&next_states)

.gather(1, &next_actions.unsqueeze(1), false)

.squeeze();

let target_q_values = rewards + gamma * next_q_values * (1.0 - dones);

let current_q_values = q_net

.forward(&states)

.gather(1, &actions.unsqueeze(1), false)

.squeeze();

// Fixed: Added explicit type annotation for td_errors

let td_errors: Tensor = current_q_values - target_q_values;

let loss = (weights_tensor * td_errors.pow(&Tensor::from(2.0))).mean(Kind::Float);

optimizer.zero_grad();

loss.backward();

optimizer.step();

}

state = next_state;

}

// Update target network

if episode % target_update_interval == 0 {

target_vs.copy(&vs).unwrap();

}

// Decay epsilon

epsilon = epsilon_end + (epsilon - epsilon_end) * epsilon_decay;

println!(

"Episode {}: Total Reward: {}, Epsilon: {:.3}",

episode + 1,

total_reward,

epsilon

);

}

}

fn main() {

println!("Starting Double DQN training with Prioritized Experience Replay...");

train_double_dqn();

}

The CartPole environment simulates a physics-based control task where the goal is to balance a pole on a moving cart. The environment calculates the next state using physical laws such as Newtonian mechanics. The step function computes the cart's position, velocity, pole angle, and angular velocity based on the action taken, returning the next state, a reward of 1 for a balanced state, and a boolean indicating whether the episode has terminated. The environment is reset with random initial conditions for each new episode.

During training, the Double DQN algorithm alternates between interacting with the environment and learning from collected experiences. The agent selects actions using an epsilon-greedy policy, balancing exploration and exploitation. The experience tuple, comprising the current state, action, reward, next state, and done flag, is stored in a prioritized replay buffer. The prioritization ensures that more significant experiences (with higher temporal difference errors) are sampled more frequently, improving learning efficiency.

The agent learns by sampling mini-batches from the replay buffer. Using the Double DQN approach, the online network selects the best action for the next state, while the target network evaluates its Q-value. This separation reduces the overestimation bias inherent in traditional Q-learning. The temporal difference (TD) error between the predicted and target Q-values is calculated and used to update the network parameters via backpropagation.

The target network is periodically synchronized with the online network to stabilize learning. Additionally, epsilon is decayed over episodes to reduce exploration in favor of exploitation as the agent becomes more competent. At the end of each episode, the total reward and the current epsilon value are printed, providing insights into the agent's learning progress. This process continues for a predefined number of episodes or until the agent consistently performs well in the environment.

The Prioritized Replay Buffer enhances learning efficiency by storing transitions along with their priorities, calculated using the temporal-difference (TD) error. Transitions with higher errors are sampled more frequently, as they are considered more informative for learning. Additionally, the buffer applies importance sampling weights to correct for any bias introduced by the prioritization, ensuring that the optimization remains unbiased over time. During training, a batch of transitions is sampled from the replay buffer, and the Q-values for the current states and actions are computed using the main network. The target Q-values are calculated using the target network and the Bellman equation, which incorporates the rewards and the maximum Q-value of the next state. The difference between the predicted Q-values and the targets (the TD error) is used to compute the loss, which is minimized through backpropagation.

The target network is updated periodically to synchronize its weights with the main network. This periodic update prevents the instability that can arise from the moving target problem, where the network being optimized also determines the Q-value targets. Over time, the agent learns to maximize the cumulative reward by predicting Q-values that better align with the expected returns. The combination of Double DQN, which mitigates overestimation of Q-values, and Prioritized Experience Replay, which focuses on critical transitions, ensures efficient and robust learning of the CartPole balancing task. The implementation demonstrates how modern reinforcement learning techniques can address complex decision-making problems by leveraging neural networks, experience replay, and targeted exploration-exploitation strategies.

During each episode, the agent selects actions either randomly (for exploration) or based on the Q-values output by the network. The selected action is executed in the environment, which returns the next state and reward. These interactions are stored in the replay buffer. When the buffer contains enough experiences, the agent samples a batch to update the Q-network using stochastic gradient descent (SGD). The network computes the current Q-values for each state-action pair, and the target Q-values are calculated using the Bellman equation:

$$ y = r + \gamma \max_{a'} Q(s', a'; \theta^-), $$

where $r$ is the immediate reward, $s'$ is the next state, $\gamma$ is the discount factor, and $\theta^-$ are the parameters of the target network. The loss function minimizes the squared difference between the predicted Q-values and these target Q-values, allowing the Q-network to improve its predictions over time.

The code periodically updates the target network by copying the weights from the Q-network, providing a stable target for learning. This update process helps the agent to converge towards an optimal policy, reducing the fluctuations that could occur if both networks were updated simultaneously. The training loop continues for a specified number of episodes, and the agent's total reward for each episode is printed, providing a measure of its performance.

This implementation of DQN demonstrates how to build a reinforcement learning agent capable of learning from high-dimensional inputs using neural networks, and it showcases the integration of advanced concepts like experience replay and target networks. By experimenting with different hyperparameters, network architectures, and exploration strategies, we can adapt the DQN to solve various control problems, from balancing a CartPole to navigating more complex simulated environments. The combination of Rust’s performance with the flexibility of deep learning makes this approach highly suitable for developing efficient, production-ready RL solutions.

In summary, Deep Q-Networks (DQN) extend the capabilities of reinforcement learning by integrating deep learning to approximate action-value functions in complex, high-dimensional environments. The combination of experience replay, target networks, and techniques like Double DQN makes DQN a robust framework for learning optimal policies in a wide range of applications, from gaming and robotics to autonomous systems and financial trading. While challenges such as overestimation bias and the need for efficient exploration remain, DQN's contributions to reinforcement learning have made it a cornerstone in the field, demonstrating the power of deep learning to enable intelligent decision-making in dynamic and uncertain environments.

16.3. Policy Gradient Methods

Policy Gradient Methods represent a fundamental approach in reinforcement learning (RL), offering a direct way to optimize a policy without the intermediate step of estimating value functions. Unlike value-based methods like Q-learning, which aim to estimate the value of taking certain actions in specific states, policy gradient methods directly adjust the parameters of the policy to maximize the expected rewards. These methods are particularly advantageous in environments with continuous action spaces, where the discrete nature of value-based methods may be inadequate. A policy in this context is a function $\pi_{\theta}(a \mid s)$ that outputs a probability distribution over actions aaa, given a state $s$, parameterized by $\theta$, which are the weights of a neural network. The objective of policy gradient methods is to find the optimal parameters $\theta$ that maximize the expected cumulative reward:

$$ J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_{\theta}} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t R(s_t, a_t) \right], $$

where $\tau$ represents a trajectory $(s_0, a_0, s_1, a_1, \ldots)$ generated by the policy $\pi_{\theta}$, $R(s_t, a_t)$ is the reward received at time $t$, and $\gamma \in [0,1]$ is the discount factor that determines the weight of future rewards relative to immediate rewards. The goal is to adjust $\theta$ such that the policy $\pi_{\theta}$ generates trajectories that maximize $J(\theta)$, effectively guiding the agent towards strategies that yield higher long-term rewards.

Figure 3: Key concept of policy gradient method.

The Policy Gradient Theorem provides the mathematical basis for computing the gradient of the expected reward $J(\theta)$ with respect to the policy parameters $\theta$. It states that the gradient can be expressed as:

$$ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_{\theta}} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t \mid s_t) G_t \right], $$

where $G_t$ is the reward-to-go or the cumulative future reward from time ttt:

$$ G_t = \sum_{k=t}^{\infty} \gamma^{k-t} R(s_k, a_k). $$

The term $\nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t \mid s_t)$ is known as the score function or policy gradient, which measures how the probability of selecting a particular action changes as the policy parameters are adjusted. This expression shows that the gradient of $J(\theta)$ is the expected value of the product of the score function and the reward-to-go $G_t$. By weighting the gradient with the cumulative rewards, the method effectively encourages actions that lead to higher rewards, updating the parameters $\theta$ in the direction that improves the expected outcome.

A practical implementation of the Policy Gradient Theorem is the REINFORCE algorithm, which is a Monte Carlo policy gradient method. Unlike Temporal Difference (TD) learning methods, REINFORCE estimates the gradient by sampling complete trajectories from the environment. The policy parameters $\theta$ are updated using the following rule:

$$ \theta \leftarrow \theta + \alpha \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t \mid s_t) G_t, $$

where $\alpha$ is the learning rate, controlling the step size during parameter updates. At each iteration, the agent interacts with the environment to collect trajectories, computes the gradient of the log-probabilities weighted by the cumulative rewards, and adjusts the policy parameters accordingly. This iterative process gradually improves the policy. However, due to the variance inherent in sampling entire trajectories, REINFORCE often suffers from high variance in its gradient estimates, which can slow down or destabilize the learning process.

One of the main challenges in policy gradient methods, particularly in REINFORCE, is the high variance in gradient estimates, which can result in slow convergence. To address this, a baseline function $b(s_t)$ can be introduced to reduce variance without introducing bias into the gradient estimation:

$$ \nabla_{\theta} J(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{\tau \sim \pi_{\theta}} \left[ \sum_{t=0}^{\infty} \nabla_{\theta} \log \pi_{\theta}(a_t \mid s_t) (G_t - b(s_t)) \right]. $$

A common choice for $b(s_t)$ is the state-value function $V^{\pi}(s)$, which estimates the expected return starting from state $s$. By subtracting $V^{\pi}(s)$ from $G_t$, we obtain the advantage function:

$$ A^{\pi}(s, a) = G_t - V^{\pi}(s), $$

which measures how much better taking action aaa in state $s$ is compared to the average performance at state $s$. This adjustment does not change the expected value of the gradient but can significantly reduce its variance, leading to more stable and efficient learning.

Sample efficiency is another challenge for policy gradient methods, as they often require a large number of interactions with the environment to converge. To improve sample efficiency, Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) methods are commonly employed. These methods combine the policy gradient approach (the actor) with a critic, which estimates the value function $V^{\pi}(s)$. The actor updates the policy parameters using the advantage estimates:

$$ A^{\pi}(s, a) = Q^{\pi}(s, a) - V^{\pi}(s), $$

where $Q^{\pi}(s, a)$ is the action-value function, representing the expected return when taking action $a$ in state $s$ and following the policy $\pi$ thereafter. The critic learns to minimize the mean squared error between $V^{\pi}(s)$ and the observed returns, providing a more stable estimate of the value function. This allows the actor to focus on actions that provide higher-than-average returns, improving the overall efficiency of the learning process.

Policy gradient methods are particularly well-suited for applications involving continuous control, adaptive strategies, and dynamic environments. For example, in robotics, policy gradient methods are used to learn control policies for tasks such as locomotion, object manipulation, and robotic arm movement. These methods can optimize actions directly, making them ideal for environments where precise control is needed.

In autonomous driving, policy gradient methods are used to train agents for continuous navigation tasks where vehicles must make real-time decisions based on continuous inputs from sensors like lidar and cameras. The ability to optimize policies for smooth control and collision avoidance is critical for navigating complex environments.

Game AI has also benefited greatly from policy gradient methods, as seen in strategy games like StarCraft II and Go, where agents must learn complex strategies that adapt to opponents' actions. By learning directly from the reward structure of the game, these methods enable agents to develop sophisticated tactics that outperform traditional rule-based systems.

In healthcare, policy gradient methods are applied to personalized treatment optimization, where the agent learns to adjust treatments based on patient data to maximize long-term health outcomes. This involves adjusting medication dosages or lifestyle interventions to achieve the best possible outcomes based on continuous monitoring of patient states.

In financial trading, policy gradient methods can model trading strategies that involve continuous adjustments to buy, sell, or hold decisions. The policy is optimized to maximize returns over time, taking into account the continuous nature of market movements and trading volumes.

Policy gradient methods provide a mathematically rigorous framework for optimizing policies directly, making them highly effective in environments with continuous action spaces and complex dynamics. The Policy Gradient Theorem and its extensions like variance reduction and actor-critic methods enable these techniques to tackle challenges such as high variance and sample inefficiency. As a result, policy gradient methods have become a cornerstone of modern RL, driving advances across diverse domains, from robotics and autonomous vehicles to healthcare and financial markets. Their ability to learn directly from interaction data and optimize complex behaviors makes them crucial for developing intelligent, adaptive systems in real-world scenarios.

The following code serves as an introductory example of the policy gradient method for reinforcement learning, implemented using the tch-rs crate in Rust. The code below implements a REINFORCE algorithm for training an agent to control a simulated pendulum system. The environment models a classic control problem where a pendulum must be balanced upright by applying torque actions, with the state space consisting of the pendulum's angle and angular velocity. The simulation includes realistic physics with gravitational forces, moment of inertia, and Euler integration for state updates, while the reward function encourages keeping the pendulum vertical while minimizing both angular velocity and control effort.

use tch::{nn, nn::Module, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Tensor, Kind};

use rand::Rng;

// Policy network remains the same

fn policy_network(vs: nn::Path, state_dim: i64, action_dim: i64) -> Box<dyn Module + 'static> {

let config = nn::LinearConfig::default();

let mean_layer = nn::linear(&vs / "mean_output", 128, action_dim, config);

let log_std_layer = nn::linear(&vs / "log_std_output", 128, action_dim, config);

Box::new(

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(&vs / "layer1", state_dim, 256, config))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add(nn::linear(&vs / "layer2", 256, 128, config))

.add_fn(|xs| xs.relu())

.add_fn(move |xs| {

let mean = xs.apply(&mean_layer);

let log_std = xs.apply(&log_std_layer);

Tensor::cat(&[mean, log_std], 1)

}),

)

}

// Sample action function remains the same

fn sample_action(network_output: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let action_dim = network_output.size()[1] / 2;

let mean = network_output.slice(1, 0, action_dim, 1);

let log_std = network_output.slice(1, action_dim, action_dim * 2, 1);

let std = log_std.exp();

let noise = Tensor::randn_like(&mean);

let action = &mean + &std * noise;

let action_clone = action.shallow_clone();

let log_prob = -((action_clone - &mean).pow(&Tensor::from(2.0))

/ (Tensor::from(2.0) * std.pow(&Tensor::from(2.0))))

.sum_dim_intlist(vec![1], false, Kind::Float)

- std.log().sum_dim_intlist(vec![1], false, Kind::Float)

- Tensor::from(2.0 * std::f64::consts::PI).sqrt().log() * (action_dim as f64 / 2.0);

(action, log_prob)

}

// Improved Environment implementation

struct Environment {

state: Vec<f64>, // [angle, angular_velocity]

max_steps: usize,

current_step: usize,

dt: f64, // time step

g: f64, // gravitational constant

mass: f64, // mass of pendulum

length: f64, // length of pendulum

}

impl Environment {

fn new(max_steps: usize) -> Self {

Self {

state: vec![0.0, 0.0], // [angle, angular_velocity]

max_steps,

current_step: 0,

dt: 0.05,

g: 9.81,

mass: 1.0,

length: 1.0,

}

}

fn reset(&mut self) -> Vec<f64> {

self.current_step = 0;

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

// Initialize with random angle (-π/4 to π/4) and small random velocity

self.state = vec![

rng.gen::<f64>() * std::f64::consts::PI / 2.0 - std::f64::consts::PI / 4.0,

rng.gen::<f64>() * 0.2 - 0.1,

];

self.state.clone()

}

fn step(&mut self, action: f64) -> (Vec<f64>, f64, bool) {

self.current_step += 1;

// Clamp action to [-2, 2] range

let action = action.max(-2.0).min(2.0);

// Physics simulation

let angle = self.state[0];

let angular_vel = self.state[1];

// Calculate angular acceleration using pendulum physics

// τ = I*α where τ is torque, I is moment of inertia, α is angular acceleration

let moment_of_inertia = self.mass * self.length * self.length;

let gravity_torque = -self.mass * self.g * self.length * angle.sin();

let control_torque = action;

let angular_acc = (gravity_torque + control_torque) / moment_of_inertia;

// Update state using Euler integration

let new_angular_vel = angular_vel + angular_acc * self.dt;

let new_angle = angle + new_angular_vel * self.dt;

// Update state

self.state = vec![new_angle, new_angular_vel];

// Calculate reward

// Reward is based on keeping the pendulum upright (angle near 0)

// and minimizing angular velocity and control effort

let angle_cost = angle.powi(2);

let velocity_cost = 0.1 * angular_vel.powi(2);

let control_cost = 0.001 * action.powi(2);

let reward = -(angle_cost + velocity_cost + control_cost);

// Check if episode is done

let done = self.current_step >= self.max_steps

|| angle.abs() > std::f64::consts::PI; // Terminal if angle too large

(self.state.clone(), reward, done)

}

fn is_done(&self) -> bool {

self.current_step >= self.max_steps ||

self.state[0].abs() > std::f64::consts::PI

}

}

// REINFORCE update function remains the same

fn reinforce_update(

optimizer: &mut nn::Optimizer,

log_probs: &Vec<Tensor>,

rewards: &Vec<f64>,

gamma: f64,

) {

let reward_to_go: Vec<f64> = rewards

.iter()

.rev()

.scan(0.0, |acc, &r| {

*acc = r + gamma * *acc;

Some(*acc)

})

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

.into_iter()

.rev()

.collect();

let reward_mean = reward_to_go.iter().sum::<f64>() / reward_to_go.len() as f64;

let reward_std = (reward_to_go

.iter()

.map(|r| (r - reward_mean).powi(2))

.sum::<f64>()

/ reward_to_go.len() as f64)

.sqrt();

let normalized_rewards: Vec<f64> = if reward_std > 1e-8 {

reward_to_go.iter().map(|r| (r - reward_mean) / reward_std).collect()

} else {

reward_to_go.iter().map(|r| r - reward_mean).collect()

};

optimizer.zero_grad();

let policy_loss = log_probs

.iter()

.zip(normalized_rewards.iter())

.map(|(log_prob, &reward)| -log_prob * reward)

.fold(Tensor::zeros(&[], (Kind::Float, Device::Cpu)), |acc, x| acc + x);

optimizer.backward_step(&policy_loss);

}

// Modified training loop to include episode statistics

fn train_reinforce(

policy: &dyn Module,

optimizer: &mut nn::Optimizer,

env: &mut Environment,

episodes: usize,

gamma: f64,

) {

let mut best_reward = f64::NEG_INFINITY;

for episode in 0..episodes {

let mut state = env.reset();

let mut log_probs = Vec::new();

let mut rewards = Vec::new();

let mut total_reward = 0.0;

while !env.is_done() {

let state_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&state)

.to_kind(Kind::Float)

.unsqueeze(0);

let network_output = policy.forward(&state_tensor);

let (action, log_prob) = sample_action(&network_output);

let action_value = action.double_value(&[0, 0]);

let (next_state, reward, done) = env.step(action_value);

log_probs.push(log_prob);

rewards.push(reward);

total_reward += reward;

state = next_state;

if done {

break;

}

}

reinforce_update(optimizer, &log_probs, &rewards, gamma);

// Track and display progress

if total_reward > best_reward {

best_reward = total_reward;

}

if (episode + 1) % 10 == 0 {

println!(

"Episode {}: Total Reward = {:.2}, Best Reward = {:.2}, Avg Episode Length = {}",

episode + 1,

total_reward,

best_reward,

rewards.len()

);

}

}

}

fn main() {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let state_dim = 2; // [angle, angular_velocity]

let action_dim = 1; // torque

let policy = policy_network(vs.root(), state_dim, action_dim);

let mut optimizer = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 3e-4).unwrap();

let mut env = Environment::new(200); // 200 steps max per episode

let episodes = 1000;

let gamma = 0.99;

println!("Starting REINFORCE training on pendulum environment...");

train_reinforce(&*policy, &mut optimizer, &mut env, episodes, gamma);

}

The REINFORCE implementation uses a neural network policy that outputs a Gaussian distribution over actions (torque values). The network architecture consists of two hidden layers (256 and 128 units) with ReLU activations, followed by parallel layers for the mean and log standard deviation of the action distribution. During training, actions are sampled from this distribution, and the policy is updated using policy gradient method with reward-to-go calculations. The algorithm normalizes rewards across episodes and uses the Adam optimizer to update the policy parameters in the direction that maximizes expected returns, with rewards discounted by a factor gamma (0.99). This implementation employs several practical techniques including reward normalization, action clamping, and periodic performance monitoring to ensure stable learning.

The reinforce_update function implements the REINFORCE algorithm with reward-to-go. The reward-to-go calculation sums the discounted future rewards for each time step, providing a learning signal that focuses on the future outcomes of actions rather than their immediate results. This helps reduce the variance of gradient estimates, improving the stability of training. After computing the reward-to-go, the rewards are normalized to have zero mean and unit variance, further improving convergence speed by standardizing the scale of reward signals. The normalized rewards are then used to weight the log-probabilities of actions taken during the episode, and gradient ascent is performed using the backward_step method of the optimizer to adjust the policy parameters.

The training loop in train_reinforce orchestrates the interaction between the agent and the environment over a specified number of episodes. The agent begins each episode by resetting the environment and then interacts with it until the episode terminates. For each interaction, the agent samples an action based on the state using the policy network, executes the action in the environment, and collects the log-probability of the action and the reward received. When the episode ends (i.e., when the environment signals that the task is complete), the reinforce_update function is called to update the policy based on the collected experiences. This iterative process allows the agent to learn a policy that maximizes cumulative rewards over time.

The design of this implementation allows it to adapt to a variety of continuous control tasks, such as MountainCarContinuous. The agent learns how to accelerate the car effectively to escape the steep valley by optimizing its actions based on the feedback it receives from the environment. Through repeated interactions and policy updates, the agent refines its behavior to reach the goal more consistently. This implementation also serves as a foundation for applying more sophisticated enhancements, such as using baseline functions (e.g., value function approximation) for further variance reduction, or integrating actor-critic methods for better sample efficiency. By leveraging the flexibility and performance of Rust and tch-rs, this code can be extended to address more complex tasks in robotics, autonomous navigation, and other real-world applications that involve continuous control and decision-making.

Training a policy gradient agent on a continuous control task like MountainCarContinuous involves learning a policy that can accelerate the car to reach the top of the hill. By experimenting with different baseline techniques, such as using a learned value function, we can further improve the stability and efficiency of training. In industry, policy gradient methods are used in applications that require direct optimization of complex behaviors, such as robotic control, game playing, and real-time decision-making, showcasing their potential for tasks where value-based methods may struggle.

The REINFORCE implementation described earlier emphasizes a policy gradient method, where the agent learns a probabilistic policy to maximize long-term rewards by directly optimizing the expected return. This approach, suitable for continuous control tasks like MountainCarContinuous, uses sampled trajectories and reward-to-go calculations to update the policy parameters effectively. Its reliance on policy gradients, reward normalization, and action sampling make it a foundational algorithm for reinforcement learning. However, REINFORCE can sometimes suffer from high variance in gradient estimates and inefficiencies in sample usage, which necessitate alternative methods like the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG).

The following code implements a DDPG reinforcement learning algorithm using the tch library for PyTorch bindings in Rust, addressing challenges specific to continuous action spaces. DDPG leverages an actor-critic architecture where the actor learns a deterministic policy to produce optimal actions, and the critic evaluates these actions using Q-values. The algorithm employs replay buffers to store and sample past experiences, improving sample efficiency, and uses soft updates to gradually adjust target networks, ensuring stable learning. Unlike probabilistic approaches like REINFORCE, DDPG's deterministic policies scale effectively to higher-dimensional action spaces. The program features an environment with simple dynamics, an actor network to generate actions, a critic network to evaluate them, and twin target networks to mitigate overestimation bias and stabilize convergence. This combination of techniques makes DDPG a powerful solution for complex, continuous control tasks.

use rand::prelude::SliceRandom;

use tch::{nn, nn::ModuleT, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

// Hyperparameters remain the same

const GAMMA: f64 = 0.99;

const TAU: f64 = 0.005;

const REPLAY_BUFFER_CAPACITY: usize = 100_000;

const BATCH_SIZE: usize = 128;

const MAX_EPISODES: usize = 200;

const MAX_STEPS: usize = 200;

const ACTOR_LR: f64 = 1e-4;

const CRITIC_LR: f64 = 1e-3;

// ReplayBuffer remains the same

struct ReplayBuffer {

obs: Vec<Vec<f64>>,

actions: Vec<f64>,

rewards: Vec<f64>,

next_obs: Vec<Vec<f64>>,

dones: Vec<bool>,

capacity: usize,

len: usize,

i: usize,

}

impl ReplayBuffer {

pub fn new(capacity: usize) -> Self {

Self {

obs: Vec::with_capacity(capacity),

actions: Vec::with_capacity(capacity),

rewards: Vec::with_capacity(capacity),

next_obs: Vec::with_capacity(capacity),

dones: Vec::with_capacity(capacity),

capacity,

len: 0,

i: 0,

}

}

pub fn push(&mut self, obs: Vec<f64>, action: f64, reward: f64, next_obs: Vec<f64>, done: bool) {

if self.len < self.capacity {

self.obs.push(obs);

self.actions.push(action);

self.rewards.push(reward);

self.next_obs.push(next_obs);

self.dones.push(done);

self.len += 1;

} else {

let i = self.i % self.capacity;

self.obs[i] = obs;

self.actions[i] = action;

self.rewards[i] = reward;

self.next_obs[i] = next_obs;

self.dones[i] = done;

}

self.i += 1;

}

pub fn sample(&self, batch_size: usize) -> Option<(Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor, Tensor)> {

if self.len < batch_size {

return None;

}

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

let indices: Vec<usize> = (0..self.len).collect();

let sampled_indices: Vec<usize> = indices.choose_multiple(&mut rng, batch_size).cloned().collect();

let obs_batch: Vec<_> = sampled_indices.iter().map(|&i| &self.obs[i]).cloned().collect();

let actions_batch: Vec<_> = sampled_indices.iter().map(|&i| self.actions[i]).collect();

let rewards_batch: Vec<_> = sampled_indices.iter().map(|&i| self.rewards[i]).collect();

let next_obs_batch: Vec<_> = sampled_indices.iter().map(|&i| &self.next_obs[i]).cloned().collect();

let dones_batch: Vec<_> = sampled_indices.iter().map(|&i| self.dones[i] as i32).collect();

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

Some((

Tensor::of_slice(&obs_batch.concat()).view((batch_size as i64, -1)).to_device(device).to_kind(Kind::Float),

Tensor::of_slice(&actions_batch).view((-1, 1)).to_device(device).to_kind(Kind::Float),

Tensor::of_slice(&rewards_batch).view((-1, 1)).to_device(device).to_kind(Kind::Float),

Tensor::of_slice(&next_obs_batch.concat()).view((batch_size as i64, -1)).to_device(device).to_kind(Kind::Float),

Tensor::of_slice(&dones_batch).view((-1, 1)).to_device(device).to_kind(Kind::Float)

))

}

}

// Actor network

fn build_actor(vs: &nn::Path, obs_dim: usize, act_dim: usize, max_action: f64) -> nn::Sequential {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer1", obs_dim as i64, 400, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer2", 400, 300, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer3", 300, act_dim as i64, Default::default()))

.add_fn(move |x| x.tanh() * max_action)

}

// Critic network

fn build_critic(vs: &nn::Path, obs_dim: usize, act_dim: usize) -> nn::Sequential {

nn::seq()

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer1", (obs_dim + act_dim) as i64, 400, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer2", 400, 300, Default::default()))

.add_fn(|x| x.relu())

.add(nn::linear(vs / "layer3", 300, 1, Default::default()))

}

// Soft update for target networks

fn soft_update(target_vs: &mut nn::VarStore, source_vs: &nn::VarStore, tau: f64) {

tch::no_grad(|| {

for (target, source) in target_vs

.trainable_variables()

.iter_mut()