Chapter 7

Introduction to Recurrent Neural Network (RNNs)

"Recurrent neural networks have the power to understand sequences, and by mastering their implementation, we can unlock deeper insights in temporal data." — Yoshua Bengio

Chapter 7 of DLVR provides an in-depth exploration of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), laying a strong foundation for understanding and implementing sequence models in Rust. The chapter begins by tracing the historical development of RNNs, highlighting their unique ability to capture temporal dependencies through hidden states, and contrasts them with feedforward networks. It delves into the mathematical formulations underlying RNNs, emphasizing their role in processing sequential data for tasks like natural language processing, time series forecasting, and speech recognition. The chapter then advances to Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, detailing how LSTMs address the vanishing gradient problem and manage long-term dependencies through intricate gating mechanisms. This section includes practical implementations of LSTMs in Rust, providing insights into optimizing model performance. Moving forward, the chapter introduces Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), explaining their streamlined architecture compared to LSTMs and their efficacy in reducing computational complexity while maintaining performance. The discussion extends to advanced RNN architectures, such as Bidirectional RNNs, Deep RNNs, and Attention Mechanisms, exploring their enhancements for complex sequence modeling. Finally, the chapter addresses the practical challenges of training RNNs, including techniques like Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT), gradient clipping, and regularization methods like dropout, all within the context of Rust. Through a combination of theoretical concepts and hands-on implementations, this chapter equips readers with the knowledge and tools to effectively utilize RNNs for a wide range of sequence-based applications.

7.1. Foundations of Recurrent Neural Networks

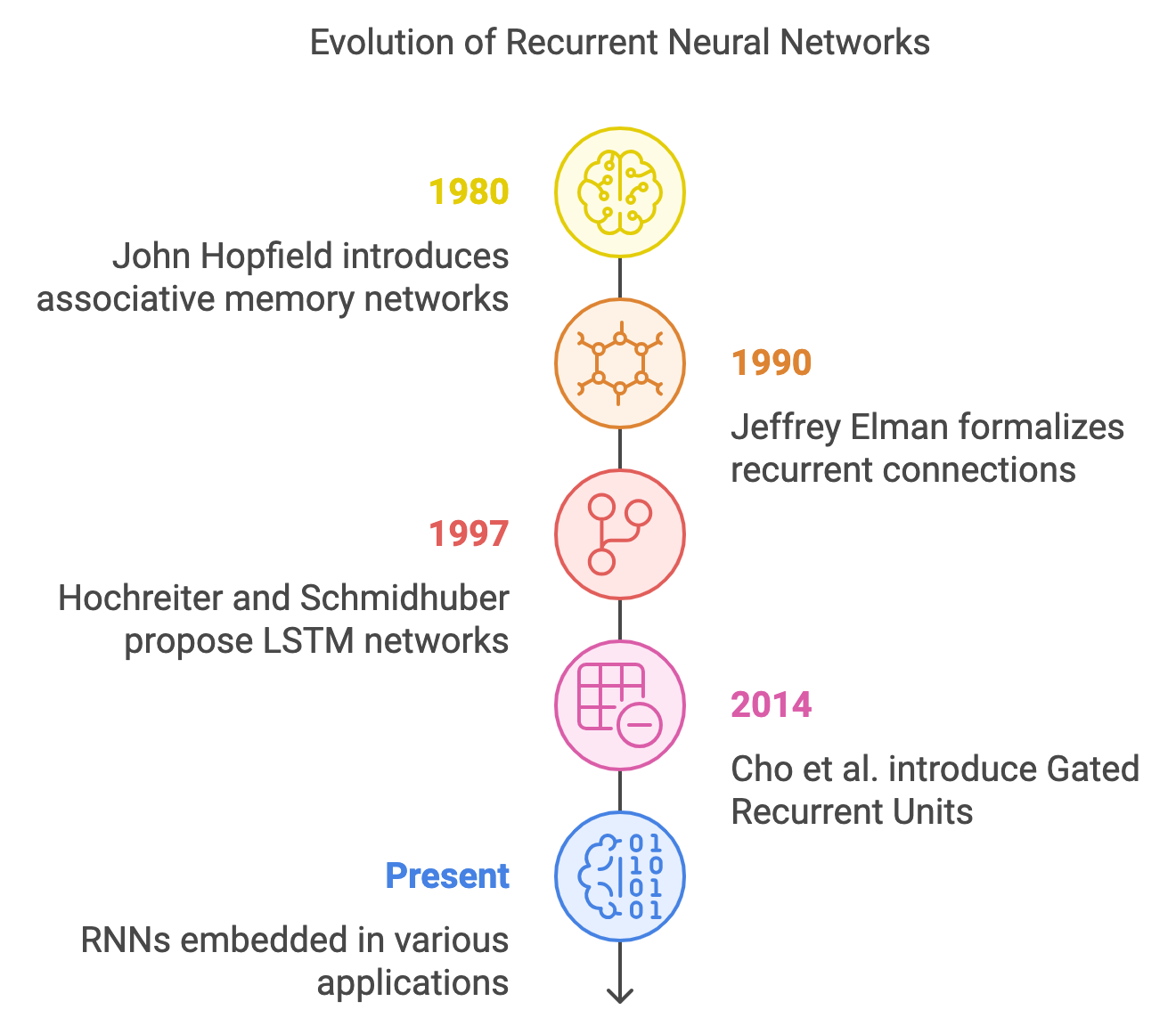

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) have a rich history that has shaped their significant impact on modern neural network architectures. The foundation of RNNs can be traced back to the early 1980s when John Hopfield introduced the concept of associative memory networks, often known as Hopfield networks. These early models laid the groundwork for the idea of using feedback connections to store and retrieve information over time, which became a fundamental principle for RNNs. In 1990, Jeffrey Elman, through his work on the “Elman Network,” formalized the idea of recurrent connections, allowing the model to maintain a memory of previous inputs and apply this context to future predictions. This feature marked a breakthrough for processing sequential data, making RNNs particularly suitable for tasks where order and temporal dependencies are crucial.

Figure 1: The evolution of Recurrent Neural Network models.

RNNs revolutionized fields such as natural language processing (NLP), speech recognition, and time series forecasting, where traditional feedforward networks faltered due to their inability to account for temporal context. The cyclic nature of RNNs enabled them to handle sequences of arbitrary lengths by processing one element at a time, while simultaneously maintaining a hidden state that encapsulated information from previous steps. Despite this innovation, early RNNs faced practical challenges, notably the "vanishing gradient" problem, which made it difficult to learn and maintain long-term dependencies. This issue arose because gradients, when propagated over many time steps during backpropagation, tended to shrink, thus preventing the network from learning effectively over long sequences.

To mitigate these limitations, new variants of RNNs were introduced in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, the most notable being Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, proposed by Hochreiter and Schmidhuber in 1997. LSTMs incorporated a more sophisticated internal architecture that allowed them to better capture long-term dependencies by using gates to control the flow of information. These gates helped regulate when information should be remembered or forgotten, allowing LSTMs to overcome the vanishing gradient problem and making them more effective for tasks that require longer contextual understanding. Another variant, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), introduced by Cho et al. in 2014, offered a simpler yet effective alternative to LSTMs, with fewer parameters while retaining their ability to handle long-range dependencies.

Today, RNNs and their variants like LSTMs and GRUs are deeply embedded in numerous applications, from machine translation and sentiment analysis to speech synthesis and financial forecasting. The evolution of RNNs has enabled neural networks to extend their reach into domains where understanding and processing sequences are crucial, marking an important chapter in the broader history of artificial intelligence and machine learning.

At the heart of RNNs is the concept of sequence modeling, where the model processes input data as a series, one step at a time, while maintaining information from previous steps. This ability to retain a memory of past information is what sets RNNs apart from feedforward networks, which treat each input independently. In RNNs, hidden states serve as a memory mechanism that evolves over time to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data. The hidden state at each time step $t$ is influenced by the input at that time $x_t$ and the hidden state from the previous time step $H_{t-1}$. The mathematical formulation of RNNs is given by:

$$ H_t = \phi(W_{xh}x_t + W_{hh}h_{t-1} + b_h) $$

where:

$W_{xh}$ represents the weight matrix between the input and the hidden state,

$W_{hh}$ represents the recurrent weight matrix between the hidden states at consecutive time steps,

$b_h$ is the bias term,

$\phi$ is a non-linear fully connected layer with activation function, typically a tanh or ReLU.

Figure 2: A Recurrent Neural Network model (Credit to d2l.ai) .

The output at each time step $t$, $y_t$, is then computed as:

$$ y_t = W_{hy}H_t + b_y $$

Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT) is the algorithm used to train Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) by applying the principles of standard backpropagation, but over time steps. BPTT extends traditional backpropagation by unrolling the RNN across multiple time steps, allowing the model to compute the gradients of the loss function with respect to each weight across the sequence. This enables the RNN to update its weights to better capture temporal dependencies in sequential data.

Assume the RNN is solving a supervised learning task, where the true output at time $t$ is denoted by $\hat{y_t}$. The loss function $L_t$ at time $t$ is typically defined using a suitable loss function such as Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression or Cross-Entropy Loss for classification:

$$ L_t = \mathcal{L}(y_t, \hat{y_t}) $$

The total loss $L$ over the sequence is the sum of the losses at each time step: $L = \sum_{t=1}^{T} L_t$, where $T$ is the total number of time steps.

The goal of BPTT is to compute the gradients of the total loss $L$ with respect to the model parameters $W_{xh}, W_{hh}, W_{hy}, b_h, b_y$ and update the parameters using gradient descent.

The loss at time $t$ depends not only on the hidden state at time $t$, $H_t$, but also on all the previous hidden states $H_{t-1}, H_{t-2}, \dots$ due to the recursive nature of RNNs. This dependency is what makes RNNs powerful for sequence modeling, but it also makes training more challenging. BPTT computes the gradients by recursively applying the chain rule across the sequence.

The derivative of the loss $L_t$ at time ttt with respect to $W_{hy}$ is computed as:

$$ \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial W_{hy}} = \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial y_t} \cdot \frac{\partial y_t}{\partial W_{hy}} = \delta_t \cdot H_t^T $$

where $\delta_t = \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial y_t}$ is the error term at time $t$.

The error at the output layer is backpropagated through time to compute the gradients with respect to the hidden states $H_t$. The gradient of the loss with respect to the hidden state at time $t$ is:

$$\frac{\partial L_t}{\partial H_t} = \delta_t \cdot W_{hy}$$

However, since the hidden state $H_t$ also influences the loss at future time steps, the total gradient of the loss with respect to $H_t$ includes contributions from future time steps:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial H_t} = \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial H_t} + \sum_{k=t+1}^{T} \frac{\partial L_k}{\partial H_t} $$

The weight matrix $W_{hh}$, which connects the hidden states across time steps, requires special handling because the hidden state $H_t$ depends on the previous hidden state $H_{t-1}$. Using the chain rule, the gradient of the loss with respect to $W_{hh}$ is:

$$\frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{hh}} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \left( \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial H_t} \cdot \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial W_{hh}} \right)$$

The term $\frac{\partial H_t}{\partial W_{hh}}$ is influenced by the hidden state from the previous time step $H_{t-1}$, which introduces the recursive nature of BPTT. The recursive gradient computation for the hidden states can be expressed as:

$$ \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial W_{hh}} = \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial H_{t-1}} \cdot \frac{\partial H_{t-1}}{\partial W_{hh}} $$

This recursion continues until the first time step $t = 1$.

Similarly, the gradient of the loss with respect to the input-to-hidden weight matrix $W_{xh}$ is:

$$ \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{xh}} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \left( \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial H_t} \cdot \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial W_{xh}} \right) $$

where $\frac{\partial H_t}{\partial W_{xh}} = x_t$. The gradients with respect to the bias terms $b_h$ and $b_y$ are computed in a similar manner:

$$\frac{\partial L}{\partial b_h} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \frac{\partial L_t}{\partial H_t}$$

$$\frac{\partial L}{\partial b_y} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \delta_t$$

Once the gradients are computed using BPTT, the weights are updated using gradient descent (or any variant like Adam):

$$ W_{xh} \leftarrow W_{xh} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{xh}} $$

$$ W_{hh} \leftarrow W_{hh} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{hh}} $$

$$ W_{hy} \leftarrow W_{hy} - \eta \frac{\partial L}{\partial W_{hy}} $$

where $\eta$ is the learning rate.

RNNs excel in tasks where the order and structure of data are crucial, making them invaluable in domains such as natural language processing (NLP), time series forecasting, and speech recognition. In NLP, understanding the meaning of a sentence depends on the sequence of words and their contextual relationships. Similarly, in time series forecasting, predicting future trends like stock prices or weather patterns requires learning temporal dependencies from past observations. Speech recognition relies on processing sequences of phonemes, where each sound contributes to forming meaningful words. The recurrent connections in RNNs, which allow hidden states to evolve over time, are fundamental for capturing these sequential patterns and dependencies effectively.

A character-level language model is a specialized application of RNNs that predicts the next character in a sequence based on its preceding context, enabling the generation of text one character at a time. By operating at the character level, these models capture finer-grained patterns such as word structures, punctuation styles, and linguistic nuances. This makes them suitable for tasks that demand flexibility, such as generating stylistically consistent text, creating code, or handling rare word compositions. Training such models involves feeding sequences of characters into the RNN, updating its parameters via backpropagation through time, and refining its ability to model patterns and dependencies in the text. These models leverage the temporal processing strengths of RNNs to handle diverse textual data with high granularity.

This example demonstrates a character-level language model inspired by [char-rnn](https://github.com/karpathy/char-rnn), which is designed to learn patterns in text data at the character level. The model is trained on a large text file, such as the "tiny Shakespeare dataset," to predict the next character in a sequence given its preceding characters. Training involves adjusting the model's parameters to minimize the prediction error, enabling it to generate coherent text sequences based on the learned patterns. After training, the model can generate new text by seeding it with a starting sequence. It iteratively predicts the next character, sampling from the predicted distribution to produce a sequence of text. This process mimics how a human might write character-by-character, guided by learned rules of grammar and style.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

tch = "0.12"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

flate2 = "1.0"

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{Linear, OptimizerConfig};

use tch::{nn, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants for training configuration

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

/// Downloads the dataset if it doesn't exist locally.

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?; // Create the parent directory if needed

fs::write(path, content)?; // Save the dataset to the specified path

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

/// Custom RNN module for character-level modeling.

struct CustomRNN {

ih: Linear, // Input-to-hidden layer

hh: Linear, // Hidden-to-hidden layer

ho: Linear, // Hidden-to-output layer

}

impl CustomRNN {

/// Constructor to initialize the RNN with input, hidden, and output layers.

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, input_size: i64, hidden_size: i64, output_size: i64) -> Self {

let ih = nn::linear(vs, input_size, hidden_size, Default::default());

let hh = nn::linear(vs, hidden_size, hidden_size, Default::default());

let ho = nn::linear(vs, hidden_size, output_size, Default::default());

Self { ih, hh, ho }

}

/// Forward pass through the RNN for a single timestep.

fn forward(&self, input: &Tensor, hidden: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let hidden_next = (input.apply(&self.ih) + hidden.apply(&self.hh)).tanh(); // Compute next hidden state

let output = hidden_next.apply(&self.ho); // Compute output from the hidden state

(output, hidden_next)

}

/// Initialize the hidden state with zeros.

fn zero_hidden(&self, batch_size: i64, device: Device) -> Tensor {

Tensor::zeros([batch_size, HIDDEN_SIZE], (Kind::Float, device))

}

}

/// Generate sample text using the trained RNN.

fn sample(data: &TextData, rnn: &CustomRNN, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut hidden = rnn.zero_hidden(1, device); // Initialize hidden state

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with the first label

let mut result = String::new();

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // One-hot input

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the input for the last label

let (output, next_hidden) = rnn.forward(&input, &hidden); // Forward pass

hidden = next_hidden; // Update the hidden state

// Sample the next character from the output distribution

let sampled_y = output

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

last_label = sampled_y;

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Append the sampled character

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?; // Load the text dataset

let labels = data.labels(); // Number of unique labels (characters)

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the custom RNN model

let rnn = CustomRNN::new(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, labels);

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0; // Accumulate loss

let mut batch_count = 0.0; // Count batches

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels); // Input sequences

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64); // Target sequences

let mut hidden = rnn.zero_hidden(BATCH_SIZE, device); // Initialize hidden state

let mut outputs = Vec::new(); // Collect outputs for all timesteps

for t in 0..SEQ_LEN {

let input = xs.narrow(1, t, 1).squeeze_dim(1).to_device(device); // Extract timestep input

let (output, next_hidden) = rnn.forward(&input, &hidden); // Forward pass

hidden = next_hidden; // Update hidden state

outputs.push(output); // Store output

}

// Stack outputs and compute loss

let logits = Tensor::stack(&outputs, 1).view([-1, labels]);

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([-1]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5); // Gradient clipping

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Convert loss to f64

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &rnn, device)); // Generate sample text

}

Ok(())

}

The example highlights how the model evolves its ability to generate text over training epochs. After just five epochs on the Shakespeare dataset, the model begins to produce text resembling Shakespearean language, including character names, dialogue structures, and poetic styles. While the generated text may include errors and nonsensical words at early stages, it captures the rhythm, syntax, and some thematic elements of the original text. The practical simplicity of this setup, using widely available text files and running through a Rust-based implementation, makes it a compelling demonstration of how neural networks can learn and generate sequential data at a granular level.

A fundamental distinction between RNNs and feedforward networks is that RNNs maintain memory through hidden states, making them capable of processing input sequences as opposed to treating each input independently. This is crucial for tasks like machine translation, where the meaning of a word depends on the words that precede it. RNNs thus allow models to "remember" and incorporate prior context while making predictions.

The recurrent connection in RNNs—where the hidden state from the previous time step $h_{t-1}$ feeds into the current computation—helps the model to capture temporal patterns and dependencies across time steps. However, this also makes training more complex, as issues like vanishing and exploding gradients can occur when propagating errors through long sequences, which led to the development of advanced variants like LSTMs and GRUs.

This Rust code demonstrates the process of training a simple RNN using synthetic sine wave data with added noise. The data is generated with a sine function (sin(x)) and random noise. A custom SimpleRNN model is implemented with input-to-hidden, hidden-to-hidden, and hidden-to-output layers using the tch-rs crate, which facilitates tensor operations and neural network construction. The training loop uses mean squared error (MSE) loss and an Adam optimizer to minimize the error between the predicted and actual values over 500 epochs. The model is trained to predict the next value in a sequence of sine wave data. The synthetic data is split into training and testing sets, with the model processing the data in windows of a specified size (input_window). The hidden state is updated with each timestep, and the model learns to predict future values in the noisy sine wave sequence. The code leverages the GPU if available for training, and prints the loss and sample predictions every 50 epochs.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

tch = "0.12"

rand = "0.8.5"

use tch::{nn, nn::OptimizerConfig, Device, Kind, Tensor};

use rand::Rng;

// Generate synthetic sine wave data with noise

fn generate_synthetic_data(size: usize) -> Vec<f64> {

let mut data = Vec::with_capacity(size);

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

for i in 0..size {

let noise: f64 = rng.gen_range(-0.2..0.2);

data.push((i as f64 / 10.0).sin() + noise); // Sine wave + noise

}

data

}

// Custom RNN structure

struct SimpleRNN {

ih: nn::Linear, // Input-to-hidden weights

hh: nn::Linear, // Hidden-to-hidden weights

ho: nn::Linear, // Hidden-to-output weights

}

impl SimpleRNN {

fn new(vs: &nn::Path, input_size: i64, hidden_size: i64, output_size: i64) -> Self {

let ih = nn::linear(vs, input_size, hidden_size, Default::default());

let hh = nn::linear(vs, hidden_size, hidden_size, Default::default());

let ho = nn::linear(vs, hidden_size, output_size, Default::default());

Self { ih, hh, ho }

}

fn forward(&self, input: &Tensor, hidden: &Tensor) -> (Tensor, Tensor) {

let hidden_next = (input.apply(&self.ih) + hidden.apply(&self.hh)).tanh(); // Update hidden state

let output = hidden_next.apply(&self.ho); // Compute output

(output, hidden_next)

}

fn zero_hidden(&self, batch_size: i64, hidden_size: i64, device: Device) -> Tensor {

Tensor::zeros([batch_size, hidden_size], (Kind::Float, device)) // Ensure f32 dtype

}

}

fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn std::error::Error>> {

// Generate synthetic data

let data = generate_synthetic_data(200);

let input_window = 10; // Input window size

let train_size = 150;

// Split data into training and testing sets

let (train_data, test_data): (Vec<f64>, Vec<f64>) = (

data[..train_size].to_vec(), // Convert slice to Vec

data[train_size..].to_vec(), // Convert slice to Vec

);

// Prepare training inputs and targets

let train_input: Vec<_> = train_data

.windows(input_window)

.map(|w| Tensor::of_slice(w).to_kind(Kind::Float)) // Ensure f32 dtype

.collect();

let train_target: Vec<_> = train_data[input_window..]

.iter()

.map(|&v| Tensor::from(v).to_kind(Kind::Float)) // Ensure f32 dtype

.collect();

// Unused testing variables (prefixed with `_` to suppress warnings)

let _test_input: Vec<_> = test_data

.windows(input_window)

.map(|w| Tensor::of_slice(w).to_kind(Kind::Float)) // Ensure f32 dtype

.collect();

let _test_target: Vec<_> = test_data[input_window..]

.iter()

.map(|&v| Tensor::from(v).to_kind(Kind::Float)) // Ensure f32 dtype

.collect();

// Define the model

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(Device::cuda_if_available());

let rnn = SimpleRNN::new(&vs.root(), 1, 10, 1); // 1 input, 10 hidden, 1 output

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, 1e-3)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 0..500 {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

for (input, target) in train_input.iter().zip(train_target.iter()) {

let input = input.unsqueeze(0).unsqueeze(-1); // Add batch and feature dimensions

let target = target.unsqueeze(0).unsqueeze(-1);

// Initialize hidden state (not mutable anymore)

let hidden = rnn.zero_hidden(1, 10, vs.device());

let (output, _) = rnn.forward(&input, &hidden); // Forward pass

let loss = output.mse_loss(&target, tch::Reduction::Mean); // Compute loss

opt.backward_step(&loss); // Backpropagation

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Extract scalar loss value

}

if epoch % 50 == 0 {

println!("Epoch: {}, Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / train_input.len() as f64);

}

}

println!("Training complete!");

Ok(())

}

Once the model is defined, training involves iteratively feeding sequence data (e.g., stock prices, weather metrics, or sensor readings) into the RNN and refining its parameters using backpropagation through time (BPTT). The sequential nature of the data allows the RNN to maintain a hidden state that encodes information about past inputs, enabling it to learn temporal patterns and make informed predictions about future values. This iterative process is sensitive to challenges like vanishing or exploding gradients, which can be mitigated using advanced techniques such as gradient clipping, proper initialization strategies, and regularization methods like dropout.

Beyond basic time series forecasting, RNNs can be extended to handle a variety of complex sequential tasks, including natural language processing, speech recognition, and sequence classification. Their ability to model dependencies over time makes them foundational for applications like predictive analytics, language modeling, and dynamic control systems. Industry use cases abound, with RNNs powering recommendation engines, financial risk modeling, supply chain forecasting, and predictive maintenance in industrial systems. Techniques such as attention mechanisms and hybrid architectures (e.g., RNNs combined with CNNs or Transformers) further enhance their versatility and performance.

From a scientific standpoint, RNNs address one of the most critical challenges in machine learning—modeling temporal dependencies—providing solutions that have significantly advanced fields like AI and data-driven science. Rust’s expanding ecosystem, including libraries such as tch-rs and burn, equips developers with high-performance, type-safe tools to implement RNNs and integrate them into scalable and efficient pipelines. By uniting robust theoretical foundations with the practical strengths of Rust, developers can harness the power of RNNs for cutting-edge applications across domains, ensuring reliability, safety, and top-tier performance in real-world deployments.

7.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks

The Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture was developed in the mid-1990s by Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber to address a fundamental challenge in training Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): the vanishing gradient problem. This problem occurs when training traditional RNNs using the backpropagation through time (BPTT) algorithm, especially when learning long-term dependencies in sequential data.

RNNs are designed to handle sequential data by maintaining a hidden state that is updated as new inputs are processed at each time step. In theory, RNNs are capable of learning long-term dependencies by propagating information through these hidden states across time steps. The BPTT algorithm is used to compute the gradients of the loss function with respect to the network's parameters over a sequence of time steps, which allows the network to adjust its weights and learn from the data.

However, in practice, BPTT faces a critical limitation. As the gradients are propagated backward through many time steps, they often become very small, or even approach zero, in a process known as vanishing gradients. This leads to a situation where the network's weights are not updated effectively for time steps that are far from the current one, making it extremely difficult to learn long-term dependencies. Specifically, the gradient of the loss function with respect to the weights decays exponentially as it is propagated backward, which results in the network being unable to "remember" information from earlier time steps.

Mathematically, if the Jacobian matrix of the recurrent layer has eigenvalues that are less than one, the gradient $\delta$ diminishes exponentially as it is propagated back in time:

$$ \delta_t = \delta_{t+1} \cdot \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial H_{t+1}} \quad \text{where} \quad \frac{\partial H_t}{\partial H_{t+1}} \ll 1 $$

Here, $H_t$ represents the hidden state at time $t$, and $\frac{\partial H_t}{\partial H_{t+1}}$ denotes the derivative of the hidden state at time $t+1$ with respect to the hidden state at time $t$. When this derivative is much smaller than 1, the gradients shrink rapidly, leading to ineffective learning of long-term patterns.

To overcome the limitations of traditional RNNs, Hochreiter and Schmidhuber introduced LSTM networks in 1997. The core innovation of LSTMs lies in their ability to selectively retain or discard information over time through the use of memory cells and gating mechanisms. This architecture allows LSTMs to preserve important information for long periods and mitigate the vanishing gradient problem.

Figure 3: LSTM cell architecture (Credit to d2l.ai)

An LSTM cell is composed of three key gates: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate. These gates control the flow of information into, through, and out of the cell, making it possible to manage long-term dependencies without the issue of vanishing gradients. The cell state, often referred to as the memory cell, acts as a conveyor belt that runs through the network, carrying information along the entire sequence. The gates selectively allow information to be added to or removed from this memory.

Forget Gate: Decides what information should be discarded from the cell state. This is based on the previous hidden state $H_{t-1}$ and the current input $X_t$: $F_t = \sigma(W_f \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_f)$, where $\sigma$ is the FC layer with sigmoid activation function, $W_f$ is the weight matrix, and $b_f$ is the bias term.

Input Gate: Determines what new information will be stored in the cell state: $I_t = \sigma(W_i \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_i)$

and the candidate values to be added: $\tilde{C}_t = \tanh(W_C \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_C)C$.

Output Gate: Controls what part of the cell state will be output as the hidden state: $O_t = \sigma(W_o \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_o)$. The hidden state is then calculated by applying the output gate to the cell state: $H_t = o_t \cdot \tanh(C_t)$ where $C_t$ is the updated cell state.

The overall update of the cell state is determined by:

$$C_t = f_t \cdot C_{t-1} + i_t \cdot \tilde{C}_t$$

This formulation allows the LSTM to retain long-term information (via the forget gate) while updating with new information when necessary (via the input gate).

The key to LSTM's success lies in its ability to maintain a memory of relevant information over long periods. Unlike standard RNNs, where hidden states are the only mechanism for memory, LSTMs employ cell states that run uninterrupted through sequences, only updated at specific intervals by the gates. This architecture enables LSTMs to capture long-term dependencies effectively, making them a popular choice in applications like language modeling, machine translation, and video analysis.

The gating mechanisms in LSTMs allow the network to control what information is remembered and what is forgotten. This gives LSTMs the ability to manage long-term dependencies that are critical in tasks such as speech recognition, where the model needs to remember a word said several seconds ago to interpret the next word accurately. By selectively forgetting or retaining information, LSTMs are able to efficiently process sequential data where both short-term and long-term dependencies are crucial.

While LSTMs offer the advantage of retaining long-term information, they come with increased computational complexity compared to simple RNNs. Each LSTM cell requires additional parameters to operate its three gates, leading to longer training times and higher memory consumption. However, for tasks involving long sequences, LSTMs generally outperform simple RNNs, which struggle with vanishing gradients. The trade-off between using RNNs or LSTMs depends on the specific application—if the task involves short sequences, RNNs might suffice, but for tasks like language modeling or time series analysis with long dependencies, LSTMs are more suitable.

The configuration of the forget, input, and output gates determines how effectively the model can learn from data. For instance, in language modeling, a model might use the forget gate to retain the subject of a sentence across multiple time steps while the input gate updates the current word. Tuning these gates during training allows LSTMs to learn which parts of the sequence to prioritize and which to ignore, optimizing performance for the task at hand.

To demonstrate LSTM’s ability to capture long-term dependencies, we can train the network on tasks such as language modeling, where the goal is to predict the next word in a sentence based on previous words. Alternatively, in time series forecasting, the LSTM could predict future values based on historical data, learning patterns over long periods. Training an LSTM for these tasks involves feeding sequences into the model and optimizing the gate parameters to minimize the loss.

This code implements a character-level language model using a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network in Rust, utilizing the tch (PyTorch for Rust) library. The model is trained on Shakespeare's text data to learn patterns in character sequences and generate Shakespeare-like text. The program first downloads a dataset of Shakespeare's works if it's not already present locally, then processes this text data character by character to train an LSTM neural network that predicts the next character in a sequence.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

tch = "0.12"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

flate2 = "1.0"

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{self, Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, RNN}; // Import RNN trait to access LSTM methods

use tch::{Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants for training configuration

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

// Downloads the dataset if it doesn't exist locally.

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?; // Create the parent directory if needed

fs::write(path, content)?; // Save the dataset to the specified path

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

// Generate sample text using the trained LSTM.

fn sample(data: &TextData, lstm: &nn::LSTM, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = lstm.zero_state(1); // Initialize LSTM state

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with the first label

let mut result = String::new();

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // One-hot input

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the input for the last label

// Step through the LSTM and update state

state = lstm.step(&input, &state);

// Get a reference to the hidden state (first tensor) from the LSTM state

let hidden = &state.0.0; // Access first element (hidden state) by reference

// Pass through the output layer

let logits = linear.forward(hidden);

let sampled_y = logits

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

last_label = sampled_y;

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Append the sampled character

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?; // Load the text dataset

let labels = data.labels(); // Number of unique labels (characters)

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the LSTM model and output layer

let lstm = nn::lstm(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0; // Accumulate loss

let mut batch_count = 0.0; // Count batches

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels); // Input sequences

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64); // Target sequences

// Forward pass through the sequence

let (output, _) = lstm.seq(&xs.to_device(device)); // Process the entire sequence

let logits = linear.forward(&output.view([-1, labels])); // Flatten and apply output layer

// Compute loss

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([-1]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5); // Gradient clipping

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Convert loss to f64

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &lstm, &linear, device)); // Generate sample text

}

Ok(())

}

The code is structured into several key components: the download_dataset function handles data acquisition, the sample function generates new text using the trained model, and the main function orchestrates the training process. The LSTM model processes sequences of characters with a hidden size of 256 units, trained over 100 epochs with a batch size of 256 and sequence length of 180 characters. During training, it uses the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.01 and implements gradient clipping to prevent exploding gradients. The sampling process generates new text by repeatedly predicting the next character based on the current sequence, using the model's probability distributions to maintain creativity and variation in the output. The code demonstrates proper handling of tensors, device management (CPU/GPU), and state management in the LSTM, while implementing best practices for deep learning in Rust.

A key advantage of LSTMs is the ability to experiment with different configurations of gates to optimize the model’s performance. For example, increasing the forget gate's influence can allow the model to ignore short-term noise and focus on long-term patterns. Adjusting the learning rate or incorporating gradient clipping can further enhance the model’s ability to learn effectively from complex data.

LSTM networks are considered the gold standard for sequence modeling in various scientific and industry applications. In fields like finance, LSTMs are used to forecast stock prices based on historical data, while in NLP, they enable models to generate coherent sentences by retaining long-term dependencies. Rust’s performance and safety features make it an ideal choice for deploying LSTMs in real-time systems, especially in industries requiring low-latency predictions, such as autonomous driving or edge computing.

By blending theoretical rigor with practical Rust implementations, developers can take full advantage of LSTM’s powerful sequence modeling capabilities, leveraging Rust’s ecosystem to deploy efficient, scalable models in production environments.

7.3. Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)

Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) were introduced by Kyunghyun Cho and colleagues in 2014 as a streamlined and computationally efficient alternative to Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks. Both GRUs and LSTMs are part of the Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) family, designed to handle sequential data where dependencies between time steps are crucial. Traditional RNNs suffer from the vanishing gradient problem, where gradients become very small as they are propagated backward through time during training, particularly over long sequences. This results in poor performance when trying to capture long-term dependencies in data. LSTMs were introduced to solve this problem by introducing a more complex architecture with three gates—input, forget, and output gates—and a memory cell that allows the network to retain important information over longer periods while discarding irrelevant information. However, this complexity makes LSTMs computationally expensive, which can be a drawback, especially in large-scale models or tasks requiring faster training and inference.

GRUs simplify the architecture of LSTMs by reducing the number of gates and eliminating the memory cell, while still providing the capacity to capture long-term dependencies. In GRUs, two gates—an update gate and a reset gate—control the flow of information. The update gate combines the functions of the input and forget gates found in LSTMs. It determines how much of the previous hidden state should be retained and how much new information should be incorporated at the current time step. The reset gate, on the other hand, decides how much of the past information should be forgotten when generating the new hidden state. By directly updating the hidden state, GRUs remove the need for a separate memory cell. This architecture not only simplifies the network but also speeds up training and reduces the computational resources required, making GRUs highly efficient.

The GRU architecture also involves fewer parameters compared to LSTMs, which reduces the risk of overfitting when training on smaller datasets. Mathematically, the update gate controls the balance between retaining the previous hidden state and updating it with new information, while the reset gate modulates the influence of the past hidden state when computing the candidate hidden state for the current time step. These mechanisms allow GRUs to selectively filter information without the more intricate gating mechanism of LSTMs. The candidate hidden state is then combined with the previous hidden state based on the update gate, resulting in an updated hidden state that carries forward information deemed important by the network.

Although GRUs have a simpler architecture than LSTMs, they are often comparable in performance across a wide range of tasks, particularly in those where capturing long-term dependencies is essential. For example, GRUs are effective in tasks like natural language processing, speech recognition, and time-series prediction, where sequential dependencies are key. GRUs have also been applied successfully in generative models such as text and music generation. Their computational efficiency makes them particularly attractive in scenarios where training speed and resource constraints are important factors.

One of the key advantages of GRUs is their ability to balance performance and efficiency. By simplifying the network and requiring fewer parameters, GRUs can train faster than LSTMs while achieving similar accuracy in many tasks. However, in scenarios that involve extremely long sequences or tasks requiring more precise control over memory retention and forgetting, LSTMs may outperform GRUs because of their more nuanced handling of long-term memory through the use of separate gates and a memory cell. GRUs are also less prone to issues like vanishing gradients due to the gating mechanisms, making them a robust choice for handling sequential data.

GRUs have found applications in various domains, including natural language processing (NLP), where they are used in machine translation, language modeling, and text generation. In speech recognition, GRUs are employed to model temporal dependencies in audio data, enabling real-time processing and transcription tasks. In time-series prediction, GRUs have been applied to tasks such as stock price prediction, weather forecasting, and financial analysis, where the model learns to capture trends and patterns over time. Additionally, GRUs have been used in generative tasks like music composition, where the network learns the structure of musical sequences and generates new compositions based on learned patterns.

Figure 4: GRU cell architecture (Credit to d2l.ai).

A GRU cell consists of two gates: the update gate and the reset gate. These gates control the flow of information, allowing GRUs to maintain memory of important information across time steps while discarding irrelevant details. The simpler architecture of GRUs, compared to LSTMs, results in fewer parameters and faster training, without sacrificing much performance.

Update Gate: This gate controls how much of the past information to carry forward to the future. It combines the functions of the forget and input gates from the LSTM: $Z_t = \sigma(W_z \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_z)$, where $Z_t$ is the update gate, $W_z$ is the weight matrix, and $\sigma$ is the FC layer with sigmoid activation function.

Reset Gate: The reset gate determines how much of the previous hidden state should be forgotten when computing the new hidden state: $R_t = \sigma(W_r \cdot [H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_r)$.

New Hidden State: The hidden state is updated based on a combination of the reset gate and the current input: $\tilde{H}_t = \tanh(W_h \cdot [r_t \odot H_{t-1}, X_t] + b_h)$, where $\odot$ represents element-wise multiplication. Finally, the hidden state is computed as a linear interpolation between the previous hidden state and the candidate hidden state: $H_t = (1 - Z_t) \odot H_{t-1} + Z_t \odot \tilde{H}_t$.

In contrast to LSTMs, GRUs omit the explicit cell state, relying solely on the hidden state to carry information. This simpler architecture enables faster computation and reduced memory usage while still capturing complex temporal patterns.

GRUs simplify the LSTM architecture by reducing the number of gates and eliminating the separate memory cell. Instead of managing three gates (forget, input, and output) and a memory cell as in LSTMs, GRUs rely on just two gates (update and reset), which manage the flow of information in a more straightforward manner. Despite this simplification, GRUs often perform on par with LSTMs in many tasks, making them an attractive choice for applications where training time and computational resources are limited.

The update gate controls how much of the hidden state is carried forward to the next time step, allowing the network to remember relevant information. The reset gate determines how much of the previous hidden state is forgotten when calculating the new hidden state. These two gates work together to manage the flow of information, allowing the GRU to maintain memory across time steps and efficiently capture both short-term and long-term dependencies.

Rust’s performance capabilities make it a great language for implementing GRUs, particularly in scenarios where efficiency and speed are critical. Using the tch-rs library (Rust bindings for PyTorch), we can easily build and train a GRU model for a sequential data task. Like in the previous section, this Rust program implements a character-level text generation model using a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) neural network. The program processes the Tiny Shakespeare dataset, a classic benchmark for sequence modeling tasks, to learn and generate text character-by-character. It includes downloading and preparing the dataset, defining and training the GRU-based model with an additional linear output layer, and sampling generated text from the trained model. The program utilizes the tch library for PyTorch bindings in Rust, enabling seamless implementation of deep learning tasks, while also incorporating Adam optimization for training and reshaping functions for handling tensor operations.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

tch = "0.12"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

flate2 = "1.0"

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{self, Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, RNN}; // Import RNN trait

use tch::{Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants remain the same

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

// Download function remains the same

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?;

fs::write(path, content)?;

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

fn sample(data: &TextData, gru: &nn::GRU, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = gru.zero_state(1); // Initialize GRU state for batch size 1

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with an initial label

let mut result = String::new(); // Accumulate sampled characters

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

// Create a one-hot tensor for the current input character

let input = Tensor::zeros(&[1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // Shape: [batch_size, input_size]

input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the corresponding index to 1.0

// Forward pass through GRU

let new_state = gru.step(&input.unsqueeze(0), &state); // Input shape [seq_len=1, batch_size=1, input_size]

let output = &new_state.0; // Access the hidden state tensor (output of GRU)

// Compute logits using the linear layer

let logits = linear.forward(&output.reshape(&[-1, output.size()[1]])); // Use reshape for compatibility

// Sample a character from the output probabilities

let sampled_y = logits

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float) // Convert logits to probabilities

.multinomial(1, false) // Sample from probabilities

.int64_value(&[0]); // Extract the sampled index

last_label = sampled_y; // Update for the next input

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Convert index to character and append to result

state = new_state; // Update the GRU state

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the GRU model and output layer

let gru = nn::gru(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

let mut batch_count = 0.0;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass through the sequence

let (output, _) = gru.seq(&xs.to_device(device));

// Fix: Use reshape instead of view

let logits = linear.forward(&output.reshape(&[-1, HIDDEN_SIZE]));

let ys = ys.to_device(device).reshape(&[-1]);

// Compute loss

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys);

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5);

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]);

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &gru, &linear, device));

}

Ok(())

}

The program begins by ensuring the dataset is downloaded and saved locally. It initializes the model, consisting of a GRU layer to capture sequential dependencies and a linear layer for character prediction. The training loop shuffles the data and processes it in batches, performing forward passes through the GRU and computing loss using cross-entropy. Gradients are clipped to prevent exploding gradients, and the Adam optimizer updates the model weights. After each epoch, the model generates a text sample by iteratively predicting the next character based on the current state. Sampling leverages softmax for probabilities and multinomial sampling to ensure diverse outputs. The program dynamically utilizes available hardware, supporting both CPU and GPU computation.

From a scientific perspective, GRUs offer an important advancement in simplifying recurrent neural network architectures while maintaining competitive performance. Their ability to handle long-term dependencies with fewer parameters than LSTMs has made them a popular choice in research and industry alike. In speech recognition, language modeling, and financial forecasting, GRUs have proven effective in capturing sequential patterns without the computational overhead of LSTMs.

In industry, GRUs are widely used in applications requiring real-time processing or deployment in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices or IoT systems. Their fast training times make them suitable for online learning tasks, where models need to be updated frequently with new data. By leveraging Rust’s performance capabilities, developers can implement GRU models that are not only efficient but also scalable, making them a powerful tool for real-time sequence processing. In conclusion, GRUs offer a compelling balance between simplicity and performance, making them a valuable tool in the deep learning toolbox, particularly in environments where computational efficiency is paramount.

7.4. Advanced RNN Architectures

As the demand for more sophisticated sequence modeling grows, researchers and practitioners have extended standard Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) with advanced architectures such as Bidirectional RNNs, Deep RNNs, and the incorporation of Attention Mechanisms. These extensions are designed to improve the model's ability to capture dependencies in complex sequences and to focus on relevant parts of the input more effectively.

Bidirectional RNNs allow the model to capture information not only from past time steps (as in traditional RNNs) but also from future time steps. This is especially useful for tasks where the entire sequence is available beforehand, such as in machine translation or speech recognition.

Deep RNNs extend the concept of recurrent networks by stacking multiple layers of RNNs on top of each other, enabling the model to learn hierarchical features from sequences. This hierarchical approach allows the network to capture both low-level and high-level patterns in the data.

Attention Mechanisms further enhance RNNs by allowing the model to focus on different parts of the input sequence at different times, dynamically assigning weights to specific time steps based on their relevance to the current prediction. This mechanism mitigates the limitations of relying solely on hidden states for long-term dependencies.

In standard RNNs, the model processes the input sequence step-by-step in a unidirectional manner, typically from the past to the future. However, in some applications, information from future time steps can also be crucial for accurate predictions. Bidirectional RNNs address this by employing two RNN layers: one that processes the sequence in the forward direction and another in the backward direction. The hidden states from both directions are then concatenated to form a comprehensive representation of each time step:

$$H_t = [\overrightarrow{H_t}, \overleftarrow{H_t}]$$

where $\overrightarrow{H_t}$ and $\overleftarrow{H_t}$ represent the hidden states from the forward and backward passes, respectively.

A Deep RNN is created by stacking multiple RNN layers on top of each other. Each layer in the network receives the hidden state from the previous layer and passes it to the next layer, effectively allowing the model to learn increasingly abstract and complex features at each level. The deep architecture enables the network to capture both local dependencies (in the lower layers) and global patterns (in the higher layers). The output of a Deep RNN at time step $t$ is given by:

$$H_t^{(l)} = f(W_h^{(l)} H_{t-1}^{(l)} + W_x^{(l)} H_t^{(l-1)} + b_h^{(l)})$$

where $H_t^{(l)}$ is the hidden state at layer $l$, $W_h^{(l)}$ and $W_x^{(l)}$ are the weight matrices, and $f$ is a non-linear activation function.

Attention mechanisms provide a way for RNNs to focus on specific parts of the input sequence that are most relevant to the current prediction. This is particularly beneficial in tasks like machine translation, where certain words in the source language may correspond to distant words in the target language. The attention mechanism computes a set of attention weights $\alpha_{t,s}$ for each time step ttt and source time step sss, indicating the importance of each input element for the current prediction:

$$\alpha_{t,s} = \frac{\exp(e_{t,s})}{\sum_{s'} \exp(e_{t,s'})}$$

where $e_{t,s}$ is the alignment score, often computed as a dot product between the hidden state of the current time step and the hidden states of previous time steps.

Bidirectional RNNs are particularly useful for tasks where understanding both past and future context is critical. In speech recognition, for instance, the meaning of a word can depend on both previous and subsequent words. By processing the sequence in both directions, bidirectional RNNs are able to generate more accurate predictions by incorporating information from the entire sequence.

This Rust program implements a Bidirectional LSTM-based RNN for character-level text generation using the tch library, a Rust wrapper for PyTorch. The model processes sequences from the Tiny Shakespeare dataset, enabling it to learn character dependencies in both forward and backward directions. The architecture includes a bidirectional LSTM layer that captures contextual information from past and future time steps, followed by a linear layer that maps the concatenated forward and backward hidden states to character probabilities. The network is trained using cross-entropy loss and optimized with the Adam optimizer.

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{self, Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, RNN};

use tch::{Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants for training configuration

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256; // Hidden size for each direction

const BIDIRECTIONAL_HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = HIDDEN_SIZE * 2; // Total hidden size (forward + backward)

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

// Downloads the dataset if it doesn't exist locally.

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?;

fs::write(path, content)?;

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

// Generate sample text using the trained Bidirectional LSTM.

fn sample(data: &TextData, lstm: &nn::LSTM, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = lstm.zero_state(1); // Initialize LSTM state

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with the first label

let mut result = String::new();

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // One-hot input

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the input for the last label

// Step through the LSTM and update state

state = lstm.step(&input.unsqueeze(0), &state);

// Get a reference to the hidden state (first tensor) from the LSTM state

let hidden = &state.0.0; // Access first element (hidden state)

// Pass through the output layer

let logits = linear.forward(hidden);

let sampled_y = logits

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

last_label = sampled_y;

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Append the sampled character

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?; // Load the text dataset

let labels = data.labels(); // Number of unique labels (characters)

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the Bidirectional LSTM model and output layer

let lstm_config = nn::RNNConfig {

bidirectional: true, // Enable bidirectionality

..Default::default()

};

let lstm = nn::lstm(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, lstm_config);

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), BIDIRECTIONAL_HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default()); // Adjust for doubled hidden size

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0; // Accumulate loss

let mut batch_count = 0.0; // Count batches

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels); // Input sequences

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64); // Target sequences

// Forward pass through the sequence

let (output, _) = lstm.seq(&xs.to_device(device)); // Process the entire sequence

let logits = linear.forward(&output.reshape([-1, BIDIRECTIONAL_HIDDEN_SIZE])); // Adjust for bidirectional output

// Compute loss

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([-1]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5); // Gradient clipping

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]); // Convert loss to f64

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &lstm, &linear, device)); // Generate sample text

}

Ok(())

}

The program begins by downloading the Tiny Shakespeare dataset if it isn’t already present. It then initializes a bidirectional LSTM model, which processes input sequences in both forward and backward directions, effectively doubling the hidden state size. The training loop shuffles the dataset into batches, where each batch undergoes forward propagation through the bidirectional LSTM. The combined outputs of the forward and backward passes are reshaped and fed into the linear layer, which predicts the next character. Loss is computed using cross-entropy, and gradients are clipped during backpropagation to prevent exploding gradients. After training, the sample function generates text by iteratively predicting characters based on the current state, demonstrating the model's ability to learn and generate coherent sequences.

The concept of Deep RNNs brings the power of hierarchical learning to sequence data. Stacking multiple RNN layers enables the network to learn a layered representation of the input sequence, where each layer captures progressively more abstract features. This is similar to how deep convolutional networks capture hierarchical features in images. However, training deep RNNs presents challenges such as increased computational cost and the risk of vanishing gradients, which can be mitigated with techniques like residual connections or layer normalization.

The following Rust code implements a Deep Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) using stacked LSTM layers for character-level text generation. The model processes sequences from the Tiny Shakespeare dataset, learning the dependencies between characters to generate coherent text. The architecture includes three stacked LSTM layers configured to handle sequential data in a hierarchical manner, capturing low-level and high-level patterns. A linear output layer maps the final hidden state to character probabilities, enabling the model to predict the next character at each step. The tch library is used to provide PyTorch bindings in Rust, supporting efficient training and inference on both CPUs and GPUs.

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{self, Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, RNN};

use tch::{Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants for training configuration

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const NUM_LAYERS: i64 = 3; // Number of stacked LSTM layers

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

// Downloads the dataset if it doesn't exist locally.

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?;

fs::write(path, content)?;

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

// Generate sample text using the trained Deep RNN.

fn sample(data: &TextData, lstm: &nn::LSTM, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = lstm.zero_state(1); // Initialize LSTM state for batch size 1

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with the first label

let mut result = String::new();

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // One-hot input

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the input for the last label

// Step through the LSTM and update state

state = lstm.step(&input.unsqueeze(0), &state);

// Get a reference to the hidden state (first tensor) from the LSTM state

let hidden = &state.0.0; // Access the hidden state

// Pass through the output layer

let logits = linear.forward(hidden);

let sampled_y = logits

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

last_label = sampled_y;

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Append the sampled character

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the Deep LSTM model (stacked LSTM layers)

let lstm_config = nn::RNNConfig {

num_layers: NUM_LAYERS, // Number of stacked layers

batch_first: true, // Enable batch-first input/output

..Default::default()

};

let lstm = nn::lstm(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, lstm_config);

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

let mut batch_count = 0.0;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass through the sequence

let (output, _) = lstm.seq(&xs.to_device(device));

let logits = linear.forward(&output.view([-1, labels]));

// Compute loss

let loss = logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.to_device(device).view([-1]));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5); // Gradient clipping

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]);

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &lstm, &linear, device));

}

Ok(())

}

The program starts by downloading and preparing the dataset if it's not already available. The main function initializes the deep LSTM model with three stacked layers and trains it using mini-batches of character sequences. Each sequence is processed by the LSTM layers, with the outputs of one layer serving as inputs to the next, resulting in a hierarchical feature representation. The final output of the LSTM is passed through a linear layer to predict the next character. The training loop calculates the loss using cross-entropy, applies gradient clipping to stabilize training, and updates the model parameters using the Adam optimizer. After training, the sample function generates new text by iteratively feeding predicted characters back into the model, demonstrating its ability to learn and replicate the structure of the input dataset.

The introduction of Attention Mechanisms has revolutionized the way RNNs handle long sequences. Rather than relying solely on hidden states to retain information, attention mechanisms allow the model to dynamically focus on relevant parts of the sequence. This not only improves performance on tasks with long-range dependencies but also enhances the model’s interpretability, as the attention weights provide insight into which parts of the input are most important for making predictions.

The Rust program below implements a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with Attention Mechanism for character-level text generation. The architecture combines an LSTM encoder to process input sequences and a decoder equipped with an attention mechanism to focus on relevant parts of the input at each decoding step. The attention mechanism computes a weighted context vector based on the alignment between the decoder's hidden state and the encoder's outputs. This context vector is concatenated with the hidden state to enhance the decoder's predictions. The program uses the tch library for efficient tensor operations and training on CPUs or GPUs.

use anyhow::Result;

use std::fs;

use std::path::Path;

use tch::data::TextData;

use tch::nn::{self, Linear, Module, OptimizerConfig, RNN};

use tch::{Device, Kind, Tensor};

use reqwest;

// Constants for training configuration

const LEARNING_RATE: f64 = 0.01;

const HIDDEN_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const SEQ_LEN: i64 = 180;

const BATCH_SIZE: i64 = 256;

const EPOCHS: i64 = 100;

const SAMPLING_LEN: i64 = 1024;

const DATASET_URL: &str = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt";

const DATA_PATH: &str = "data/input.txt";

fn download_dataset() -> Result<()> {

let path = Path::new(DATA_PATH);

if !path.exists() {

println!("Downloading dataset...");

let content = reqwest::blocking::get(DATASET_URL)?.text()?;

fs::create_dir_all(path.parent().unwrap())?;

fs::write(path, content)?;

println!("Dataset downloaded and saved to {}", DATA_PATH);

} else {

println!("Dataset already exists at {}", DATA_PATH);

}

Ok(())

}

fn apply_attention(hidden: &Tensor, encoder_outputs: &Tensor) -> Tensor {

let attn_weights = hidden.matmul(&encoder_outputs.transpose(1, 2)).softmax(-1, Kind::Float);

attn_weights.matmul(encoder_outputs) // Context vector

}

fn sample(data: &TextData, lstm: &nn::LSTM, linear: &Linear, device: Device) -> String {

let labels = data.labels();

let mut state = lstm.zero_state(1); // Initialize LSTM state

let mut last_label = 0i64; // Start with the first label

let mut result = String::new();

// Initialize dummy encoder outputs (for simplicity, reusing the hidden state in sampling)

let encoder_outputs = Tensor::zeros([SEQ_LEN, 1, HIDDEN_SIZE], (Kind::Float, device));

for _ in 0..SAMPLING_LEN {

let input = Tensor::zeros([1, labels], (Kind::Float, device)); // One-hot input

let _ = input.narrow(1, last_label, 1).fill_(1.0); // Set the input for the last label

// Step through the LSTM and update state

state = lstm.step(&input.unsqueeze(0), &state);

// Get a reference to the hidden state (first tensor) from the LSTM state

let hidden = &state.0.0; // Access first element (hidden state)

// Apply attention mechanism

let context = apply_attention(hidden, &encoder_outputs);

// Fix: Use Tensor::cat instead of method syntax, and properly borrow tensors

let combined = Tensor::cat(&[hidden, &context], 1);

// Pass through the output layer

let logits = linear.forward(&combined);

let sampled_y = logits

.softmax(-1, Kind::Float)

.multinomial(1, false)

.int64_value(&[0]);

last_label = sampled_y;

result.push(data.label_to_char(last_label)); // Append the sampled character

}

result

}

pub fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Ensure the dataset is downloaded

download_dataset()?;

// Initialize the device (CPU or GPU)

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

let data = TextData::new(DATA_PATH)?;

let labels = data.labels();

println!("Dataset loaded, {labels} labels.");

// Define the LSTM model and output layer

let lstm = nn::lstm(&vs.root(), labels, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let attention_linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE * 2, HIDDEN_SIZE, Default::default());

let linear = nn::linear(&vs.root(), HIDDEN_SIZE, labels, Default::default());

let mut opt = nn::Adam::default().build(&vs, LEARNING_RATE)?;

// Training loop

for epoch in 1..=EPOCHS {

let mut total_loss = 0.0;

let mut batch_count = 0.0;

for batch in data.iter_shuffle(SEQ_LEN + 1, BATCH_SIZE) {

let xs = batch.narrow(1, 0, SEQ_LEN).onehot(labels);

let ys = batch.narrow(1, 1, SEQ_LEN).to_kind(Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass through the sequence

let (encoder_outputs, _) = lstm.seq(&xs.to_device(device));

let total_logits = Tensor::zeros(&[SEQ_LEN * BATCH_SIZE, labels], (Kind::Float, device));

let mut hidden_state = lstm.zero_state(BATCH_SIZE);

// Decoder with attention

for t in 0..SEQ_LEN {

let input_t = xs.narrow(1, t, 1).squeeze();

hidden_state = lstm.step(&input_t.unsqueeze(0), &hidden_state);

let hidden = &hidden_state.0.0;

let context = apply_attention(hidden, &encoder_outputs);

// Fix: Properly borrow tensors for concatenation

let combined = Tensor::cat(&[hidden, &context], 1);

let logits = attention_linear.forward(&combined).apply(&linear);

total_logits.narrow(0, t * BATCH_SIZE, BATCH_SIZE).copy_(&logits);

}

// Compute loss

let loss = total_logits.cross_entropy_for_logits(&ys.reshape(&[-1]).to_device(device));

opt.backward_step_clip(&loss, 0.5);

total_loss += loss.double_value(&[]);

batch_count += 1.0;

}

// Print epoch results

println!("Epoch: {} Loss: {:.4}", epoch, total_loss / batch_count);

println!("Sample: {}", sample(&data, &lstm, &linear, device));

}

Ok(())

}

The program begins by downloading the Tiny Shakespeare dataset, which serves as training data for character prediction. During training, the LSTM encoder processes input sequences to produce a series of hidden states (encoder outputs). In the decoding phase, the attention mechanism dynamically assigns weights to these encoder outputs based on their relevance to the current hidden state of the decoder. The weighted context vector is concatenated with the decoder's hidden state and passed through a linear layer to predict the next character. Loss is computed using cross-entropy, and the model is trained using the Adam optimizer with gradient clipping to stabilize training. After training, the sample function generates text by iteratively predicting characters, leveraging the attention mechanism to produce contextually accurate sequences.