Chapter 10

Transformer Architectures

"The Transformer model has redefined what is possible in natural language processing, pushing the boundaries of what machines can understand and generate." — Geoffrey Hinton

Chapter 10 of DLVR provides a comprehensive exploration of the Transformer architecture, a revolutionary model in deep learning introduced by the seminal paper "Attention is All You Need." The chapter begins with a thorough introduction to the origins and key components of the Transformer model, emphasizing its departure from traditional RNN/CNN approaches by leveraging self-attention mechanisms for parallel processing and global dependency capture. It delves into the multi-head self-attention mechanism, explaining how it enhances the model's ability to focus on different aspects of the input sequence simultaneously. The chapter also covers positional encoding, essential for preserving sequence order in self-attention models, and the role of feed-forward networks and layer normalization in stabilizing training and improving model convergence. Additionally, the chapter explores various Transformer variants like BERT, GPT, and T5, highlighting their innovations and applications. Finally, it provides practical guidance on training and optimizing Transformer models in Rust, addressing challenges like memory usage, computational cost, and overfitting, with hands-on examples using Rust libraries such as tch-rs and burn. This chapter equips readers with a robust understanding of the Transformer architecture and the skills to implement and optimize these models in Rust.

10.1. Introduction to Transformer Architecture

The journey of the Transformer architecture has profoundly reshaped the field of deep learning, particularly in natural language processing (NLP), and extended its reach across domains like computer vision, multimodal learning, and beyond. Before Transformers, sequential models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTMs), and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) were the predominant choice for handling sequential data. However, these models suffered from several limitations, such as computational inefficiency due to their sequential processing and difficulty in capturing long-term dependencies. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), though efficient at recognizing local patterns, also fell short when it came to modeling relationships across longer input spans. The advent of attention mechanisms, beginning with the Bahdanau attention mechanism in 2014, provided a solution by allowing models to selectively focus on relevant parts of the input, paving the way for the self-attention mechanism that became the cornerstone of the Transformer.

Figure 1: Evolutional journey of Transformer architecture.

In 2017, the Transformer architecture was formally introduced in Vaswani et al.'s paper, "Attention is All You Need." This innovation marked a departure from traditional sequence models by eliminating the need for recurrent or convolutional layers. The Transformer leveraged self-attention to compute dependencies across entire sequences in parallel, thus overcoming the bottlenecks of sequential processing. Key features such as multi-head self-attention enabled the model to focus on multiple relationships simultaneously, while positional encodings provided a way to represent the order of tokens in a sequence. These innovations established the Transformer as the state-of-the-art model for tasks like machine translation, significantly outperforming its predecessors.

The architecture's versatility was demonstrated in subsequent adaptations for language modeling. OpenAI's GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer), introduced in 2018, used a decoder-only design to perform autoregressive language modeling, showcasing the potential of large-scale pretraining followed by fine-tuning. In contrast, Google's BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) introduced a bidirectional encoder architecture in 2019, excelling at understanding context from both directions of a sequence. BERT's masked language modeling objective set new benchmarks in NLP tasks, solidifying Transformers as the foundation of modern NLP systems.

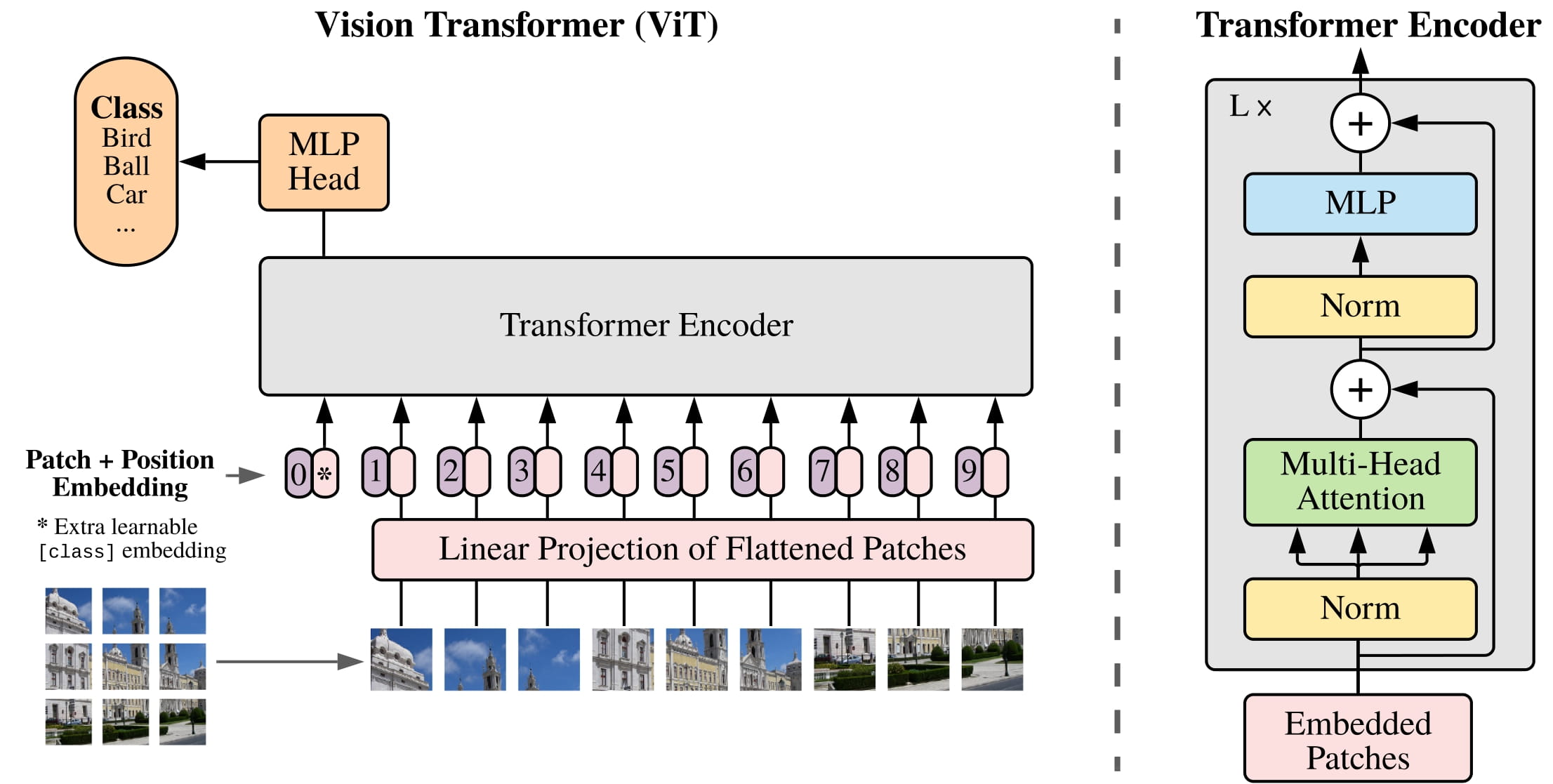

Scaling Transformers further revealed their emergent capabilities. Larger models like GPT-2 (2019) and GPT-3 (2020) demonstrated few-shot and zero-shot learning abilities, fueled by their training on vast corpora. These advancements underscored the transformative power of scale in generalization and adaptability. However, the resource-intensive nature of Transformers spurred research into more efficient variants, such as Longformer and Reformer, which addressed the quadratic complexity of standard attention mechanisms. Simultaneously, Transformers found applications beyond text, with Vision Transformers (ViTs) achieving state-of-the-art performance in image recognition and multimodal models like CLIP and DALL·E bridging text and visual data.

In recent years, research has focused on improving the efficiency, interpretability, and generality of Transformers. Instruction-tuned models like InstructGPT have aligned models with human intent, improving usability. Open-source initiatives like Hugging Face have democratized access to these models, fostering innovation and adoption across industries. Domain-specific and multilingual variants such as mBERT and BLOOM have showcased the adaptability of Transformers for diverse tasks and languages. As researchers explore incorporating memory mechanisms, retrieval systems, and symbolic reasoning into Transformer architectures, they continue to push the boundaries of what these models can achieve. The evolution of Transformers has fundamentally altered the landscape of AI, driving progress in machine learning and artificial intelligence toward solving increasingly complex problems.

Figure 2: Hugging Face becomes vibrant ecosystem for Transformer models.

The Transformer is not just a model but a paradigm shift in Artificial Intelligence, becoming the foundation for many state-of-the-art models across diverse fields. After its introduction, Transformers quickly became the dominant architecture for tasks in natural language processing (NLP), powering models such as OpenAI's GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer), Meta's Llama, and Google's Gemini. However, the impact of Transformers extends far beyond text. The architecture has been adapted for audio generation, image recognition (such as in Vision Transformers), protein structure prediction (as demonstrated by AlphaFold), and even complex decision-making processes like game playing. This versatility showcases the broad applicability of Transformers, with their ability to model relationships in data effectively across various domains.

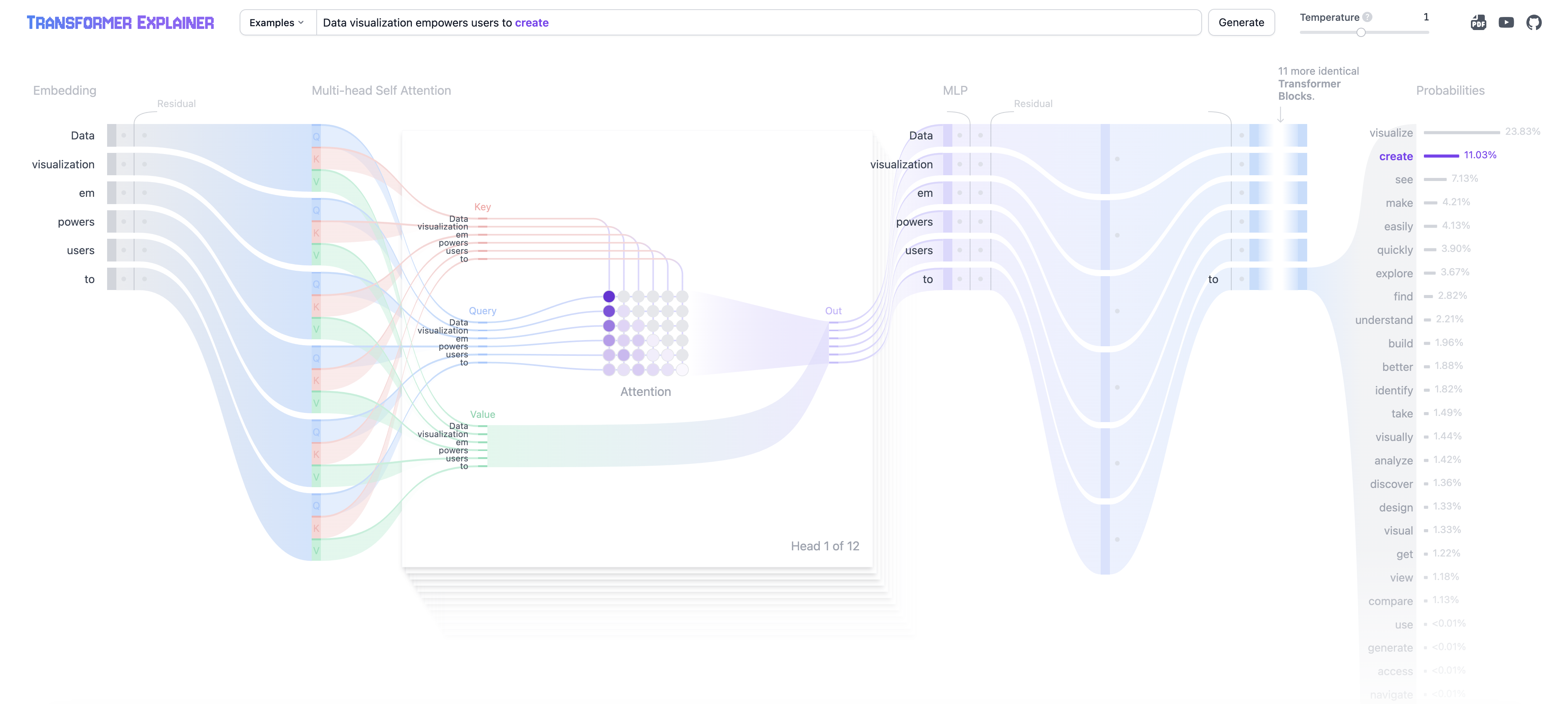

At the heart of text-generative models like GPT is the task of next-word prediction. Given a sequence of input text, the model must predict the most likely word to follow, based on the context provided by the preceding tokens. The self-attention mechanism is key to this, as it allows the model to weigh the importance of each token in the sequence relative to the others. This mechanism ensures that the model not only considers the immediate context of a word but also captures relationships between distant words, a feature that was difficult to achieve with RNNs or CNNs. The self-attention mechanism assigns attention scores to every word in the sequence, calculating how much focus each word should receive based on its relevance to the current word being processed. By doing so, the Transformer captures both local and global dependencies with ease, enabling more nuanced and contextually aware text generation.

A prominent example of a text-generative Transformer model is GPT-2, a member of the GPT family. GPT-2 (small) contains 124 million parameters and, while not the most powerful model in the GPT family, embodies many of the core architectural components that are found in cutting-edge models. GPT-2 uses a decoder-only version of the Transformer, designed to generate text in an autoregressive manner. Given a prompt, GPT-2 predicts the next word based on the previous ones, continuing this process iteratively to generate coherent and contextually relevant text. The success of models like GPT-2 lies in their ability to effectively utilize the self-attention mechanism to balance short-term context (nearby words) and long-term dependencies (words that may be far apart in the sequence). Despite newer and more powerful models like GPT-3 and GPT-4, GPT-2 remains an excellent example for understanding the fundamentals of Transformer-based text generation.

The self-attention mechanism is what sets Transformers apart. In contrast to the step-by-step processing of RNNs, self-attention allows every token in the input sequence to directly interact with every other token, leading to a quadratic number of interactions. These interactions are captured in attention maps, which visualize how much focus each token in the input sequence places on the others. This ability to focus on relevant parts of the sequence without losing sight of long-range dependencies is why Transformers excel in tasks like machine translation, where understanding both the beginning and end of a sentence is critical for generating an accurate translation. In tasks such as text summarization or language modeling, the multi-headed attention mechanism allows Transformers to process information at multiple scales, attending to both immediate neighbors and distant tokens, creating a richer and more comprehensive understanding of the input.

While the Transformer architecture is now ubiquitous in deep learning, its true power lies in its scalability. By stacking multiple layers of attention and feed-forward networks, models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and GPT have been scaled up to handle hundreds of millions or even billions of parameters. These models, pre-trained on massive corpora and fine-tuned on specific tasks, have redefined the state of the art in many areas of NLP. Transformers’ ability to handle vast amounts of data, combined with the efficiency brought by parallel processing, has allowed them to outperform traditional models across various benchmarks, cementing their place as the leading architecture in deep learning today.

Figure 3: Transformer architecture (Credit to d2l.ai).

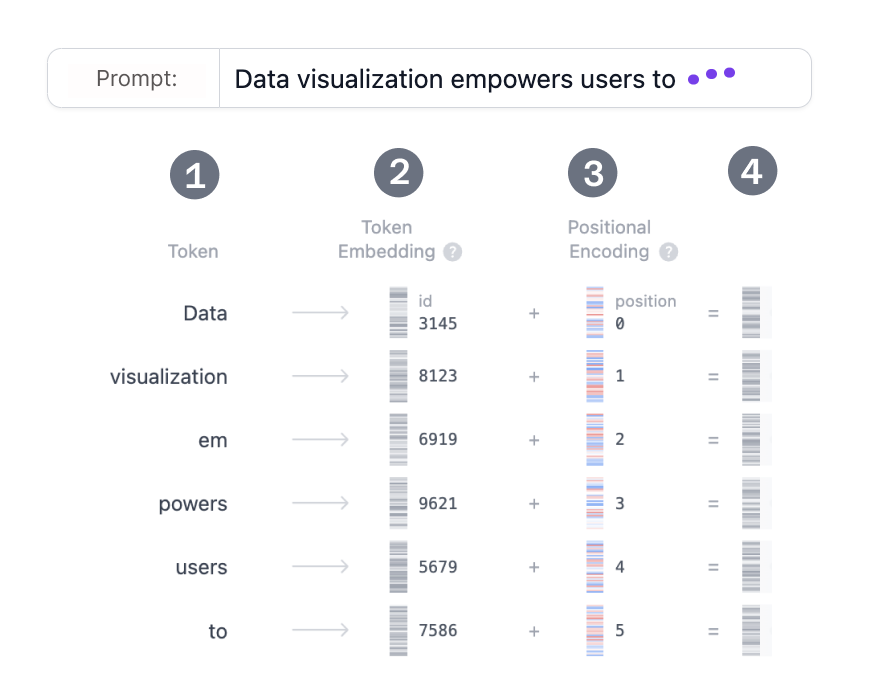

In the first stage of a Transformer model, the input text is converted into embeddings, which are numerical representations of the input tokens. Suppose we provide the prompt “Data visualization empowers users to”. The text is first tokenized, where each word or subword is assigned a unique token ID. Tokenization splits the input text into smaller units, and each token is converted into a high-dimensional vector representation called embeddings. For example, in GPT-2, the vocabulary contains 50,257 tokens, and each token is represented as a 768-dimensional vector. The collection of these vectors forms an embedding matrix $E \in \mathbb{R}^{V \times d}$, where $V$ is the vocabulary size (e.g., 50,257) and $d$ is the embedding dimension (e.g., 768). Thus, each word is mapped to a unique vector in this matrix.

Figure 4: Expanding the Embedding layer view, showing how the input prompt is converted to a vector representation. The process involves (1) Tokenization, (2) Token Embedding, (3) Positional Encoding, and (4) Final Embedding.

In tokenization, the input sequence $X = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_T\}$ is split into individual tokens, where each token $x_i$ corresponds to a word or subword unit. For each token, a unique identifier $t_i$ is assigned from a pre-defined vocabulary $V$. Formally, we can express this as:

$$x_i \mapsto t_i \quad \text{where} \quad t_i \in \{1, 2, \dots, |V|\}$$

The token identifiers are then mapped to a continuous vector space using a learned embedding matrix $E \in \mathbb{R}^{|V| \times d}$ , where $d$ is the embedding dimension. The token embeddings for the input sequence are represented as:

$$\mathbf{E} = \{E(t_1), E(t_2), \dots, E(t_T)\}$$

Here, $E(t_i)$ is the $d$-dimensional vector corresponding to the token $t_i$. For example, in GPT-2, the vocabulary $V$ has 50,257 tokens and the embedding dimension $d = 768$. Thus, the embedding matrix contains approximately $50,257 \times 768$ parameters.

Since Transformers lack a built-in mechanism to handle sequential information, positional encodings are added to the token embeddings to retain information about the order of tokens in a sequence. The positional encoding is defined using sine and cosine functions, as proposed in Vaswani et al. (2017):

$$PE_{(t, 2i)} = \sin\left(\frac{t}{10000^{\frac{2i}{d}}}\right), \quad PE_{(t, 2i+1)} = \cos\left(\frac{t}{10000^{\frac{2i+1}{d}}}\right)$$

where $t$ is the position index in the sequence, $i$ indexes the dimension of the encoding vector, and $d$ is the dimensionality of the embeddings. The final representation for each token is obtained by summing the token embedding and its corresponding positional encoding:

$$\mathbf{Z}_t = E(t) + PE(t)$$

Thus, $\mathbf{Z}_t$ captures both the semantic meaning of the token and its positional information.

The core of the Transformer model lies in the Transformer block, which consists of two main subcomponents: multi-head self-attention and multi-layer perceptron (MLP) or Feed-Forward Neural Network. Each block processes the token embeddings $\mathbf{Z}_t$ and refines them through these layers. The entire model typically stacks multiple such blocks, allowing for the development of complex representations across layers. We will discuss deeper in the next sections.

Once the input embeddings have passed through all the Transformer blocks, the model is ready to make predictions about the next token. This is achieved by projecting the final hidden representations into the vocabulary space. Given the final token representations $\mathbf{Z}$, the model computes a logit for each token in the vocabulary using a linear transformation:

$$L = \mathbf{Z} W_O + b_O$$

where $W_O \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times |V|}$ is the output weight matrix and $b_O$ is a bias term. The logits $L \in \mathbb{R}^{|V|}$ represent the unnormalized probabilities of each token in the vocabulary being the next token in the sequence.

To convert the logits into a probability distribution, the softmax function is applied:

$$P(y = i \mid \mathbf{Z}) = \frac{e^{L_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{|V|} e^{L_j}}$$

where $P(y = i \mid \mathbf{Z})$ represents the probability of token $i$ being the next token in the sequence.

To ensure stable training and prevent overfitting, several additional techniques are employed within the Transformer architecture:

Layer Normalization is applied before the self-attention and MLP sublayers to normalize the inputs across the feature dimension, stabilizing training.

Dropout is applied after each sublayer to randomly deactivate some neurons during training, reducing the risk of overfitting.

Residual Connections, first introduced by He et al. (2016), are used to bypass each sublayer, adding the input of the sublayer to its output. These shortcuts help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, enabling the training of deeper models.

The Transformer architecture, through its reliance on self-attention mechanisms and feed-forward networks, has emerged as a highly scalable and effective model for sequence processing tasks. Its ability to capture both local and global dependencies through attention, along with advanced architectural features like residual connections and layer normalization, has enabled it to outperform traditional recurrent models in tasks ranging from machine translation to text generation. By incorporating rigorous mathematical foundations, the Transformer provides an intuitive yet formal framework for understanding and processing language.

Figure 5: Transformer Explainer visual tool from https://poloclub.github.io/transformer-explainer.

Transformers offer significant advantages over traditional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), primarily due to their unique ability to process sequences in parallel and capture long-range dependencies more effectively. One of the most critical benefits of Transformers is their ability to handle entire sequences simultaneously, unlike RNNs, which process sequences step by step. This parallel processing capability makes Transformers far more efficient, especially when working with long sequences and large datasets. For instance, tasks in natural language processing (NLP), such as machine translation, text summarization, and question-answering, greatly benefit from this parallelization because Transformers can learn relationships between distant tokens in a sequence without the limitations imposed by the sequential nature of RNNs.

The multi-head attention mechanism at the heart of Transformers enables them to capture both local and global dependencies within a sequence. In contrast to RNNs and CNNs, which struggle with long-range dependencies, multi-head attention allows Transformers to focus on different parts of the input sequence simultaneously. By using multiple attention heads, Transformers can learn distinct patterns from various parts of the sequence, each head attending to different aspects of the input. This mechanism has led to the dominance of models like BERT, GPT, and T5 in NLP tasks. These models leverage self-attention to achieve state-of-the-art results in tasks like language modeling, sentiment analysis, and machine translation by understanding relationships between words that are far apart in a sentence, improving contextual understanding.

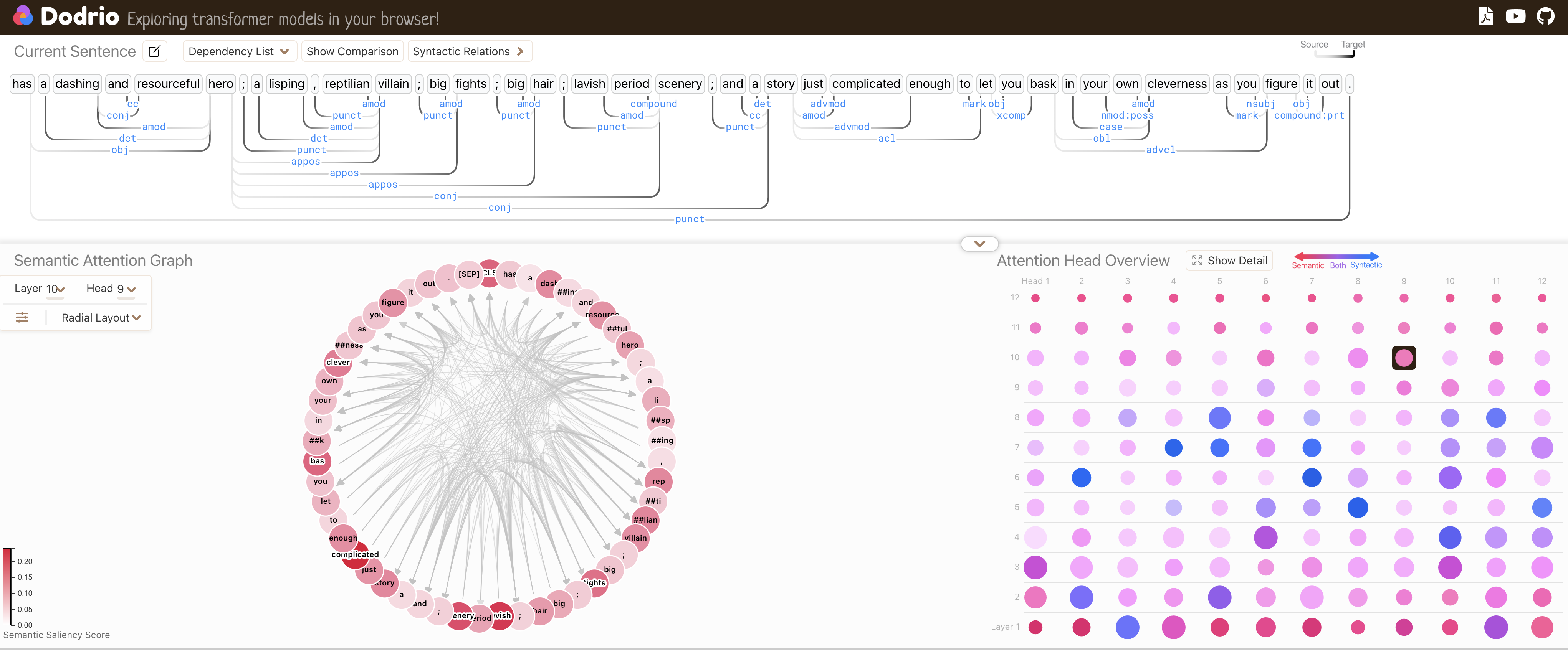

In high-performing models like BERT, there are 12 layers of attention, each with 12 separate attention heads, allowing the model to attend to multiple elements within the sequence simultaneously. The attention mechanism in each head involves calculating attention scores based on the relationships between tokens in a sentence. For example, in a sentence, each token attends to every other token in the sequence, producing an attention matrix that reflects the relevance of one token to another. In BERT, the number of attention weights computed for each text instance can be massive, as the model multiplies 12 layers by 12 attention heads and the number of tokens in the sequence. These attention heads can even capture linguistic properties like word semantics and syntactic dependencies, enabling deeper understanding across various layers of the model.

To address the complexity of interpreting attention weights in models like BERT, tools like Dodrio have been developed. Dodrio is an interactive visualization system designed to help researchers analyze attention head weights and better understand their semantic and syntactic significance. It provides an abstraction that summarizes attention heads, making it easier to explore how the model attends to different linguistic features. By using Dodrio, researchers can analyze specific attention heads, exploring their focus on core linguistic properties. For instance, if an attention head is responsible for capturing syntactic structures, it can be visualized through Dependency Views, which display lexical relationships like subject-verb-object dependencies. On the other hand, Semantic Attention Graphs visualize how certain heads capture semantic meanings or word sense disambiguation. This interactive analysis allows for deeper insights into how multi-headed attention mechanisms operate across various text instances, highlighting the importance of these heads in capturing complex linguistic phenomena such as coreference resolution, syntactic parsing, and word sense interpretation.

Figure 6: Dodrio: an interactive visualization tool to analyze and compare attention mechanisms with linguistic knowledge.

The Candle crate is a powerful and efficient Rust library designed for deep learning, offering a robust framework for building, training, and deploying machine learning models, including Transformer architectures. It emphasizes high performance and minimal overhead, making it well-suited for large-scale and computationally intensive tasks. Candle provides a flexible tensor computation engine, seamless integration with GPU acceleration, and a variety of pre-built neural network layers, including those essential for Transformers, such as self-attention, multi-head attention, and feed-forward layers. Its modular design allows developers to implement custom architectures while benefiting from the library’s optimized tensor operations and memory management. With support for state-of-the-art deep learning paradigms and a growing ecosystem, Candle empowers Rust developers to build and experiment with advanced Transformer models, bridging the gap between high-performance computing and modern AI research.

The provided code implements a sentence embedding system using a pre-trained BERT-based model from Hugging Face's sentence-transformers library. The architecture leverages the BERT model's ability to generate contextually rich embeddings for input sentences, enabling downstream tasks like similarity computation. The code incorporates key features, including tokenization with padding strategies, efficient tensor management with the Candle library, and cosine similarity computation for embedding comparison. It supports modern techniques such as GPU acceleration, safetensor format for optimized weight loading, and optional L2 normalization of embeddings for improved similarity calculations.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

candle-core = "0.8.0"

candle-examples = "0.8.0"

candle-nn = "0.8.0"

candle-transformers = "0.8.0"

clap = { version = "4", features = ["derive"] }

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

image = "0.25.5"

tokenizers = "0.20.3"

use candle_transformers::models::bert::{BertModel, Config, HiddenAct, DTYPE};

use anyhow::{Error as E, Result};

use candle_core::{Tensor, Device};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::{PaddingParams, Tokenizer};

use serde_json;

use std::fs;

/// Builds the BERT model and tokenizer using hardcoded configurations.

fn build_model_and_tokenizer() -> Result<(BertModel, Tokenizer)> {

// Configure the device: use GPU (ordinal 0) if available; otherwise, fallback to CPU.

let device = Device::cuda_if_available(0)?;

// Hardcoded model details: model ID and revision from Hugging Face.

let model_id = "sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2".to_string();

let revision = "refs/pr/21".to_string();

// Options for model loading: PyTorch weights and GELU activation approximation.

let use_pth = false;

let approximate_gelu = false;

// Fetch model files (config, tokenizer, weights) from Hugging Face repository.

let repo = Repo::with_revision(model_id.clone(), RepoType::Model, revision);

let (config_filename, tokenizer_filename, weights_filename) = {

let api = Api::new()?;

let api = api.repo(repo);

let config = api.get("config.json")?;

let tokenizer = api.get("tokenizer.json")?;

let weights = if use_pth {

api.get("pytorch_model.bin")?

} else {

api.get("model.safetensors")?

};

(config, tokenizer, weights)

};

// Load configuration JSON and tokenizer JSON.

let config_data = fs::read_to_string(config_filename)?;

let mut config: Config = serde_json::from_str(&config_data)?;

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_filename).map_err(E::msg)?;

// Initialize the model weights using either PyTorch or safetensors format.

let vb = if use_pth {

VarBuilder::from_pth(&weights_filename, DTYPE, &device)?

} else {

unsafe { VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&[weights_filename], DTYPE, &device)? }

};

// Adjust activation function to use approximate GELU if specified.

if approximate_gelu {

config.hidden_act = HiddenAct::GeluApproximate;

}

// Load the BERT model.

let model = BertModel::load(vb, &config)?;

Ok((model, tokenizer))

}

/// Main function that performs inference and similarity computation.

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Enable normalization of embeddings and specify input sentences.

let normalize_embeddings = true;

let sentences = [

"The cat sits outside",

"A man is playing guitar",

"I love pasta",

"The new movie is awesome",

"The cat plays in the garden",

"A woman watches TV",

"The new movie is so great",

"Do you like pizza?",

];

// Initialize the model and tokenizer.

let (model, mut tokenizer) = build_model_and_tokenizer()?;

let device = &model.device;

// Configure the tokenizer to pad all inputs to the longest sequence in the batch.

let n_sentences = sentences.len();

if let Some(pp) = tokenizer.get_padding_mut() {

pp.strategy = tokenizers::PaddingStrategy::BatchLongest

} else {

let pp = PaddingParams {

strategy: tokenizers::PaddingStrategy::BatchLongest,

..Default::default()

};

tokenizer.with_padding(Some(pp));

}

// Encode the input sentences into token IDs and attention masks.

let tokens = tokenizer

.encode_batch(sentences.to_vec(), true)

.map_err(E::msg)?;

let token_ids = tokens

.iter()

.map(|tokens| {

let tokens = tokens.get_ids().to_vec();

Ok(Tensor::new(tokens.as_slice(), device)?)

})

.collect::<Result<Vec<_>>>()?;

let attention_mask = tokens

.iter()

.map(|tokens| {

let tokens = tokens.get_attention_mask().to_vec();

Ok(Tensor::new(tokens.as_slice(), device)?)

})

.collect::<Result<Vec<_>>>()?;

// Stack the token IDs and attention masks into batch tensors.

let token_ids = Tensor::stack(&token_ids, 0)?;

let attention_mask = Tensor::stack(&attention_mask, 0)?;

let token_type_ids = token_ids.zeros_like()?; // Token type IDs are all zero for single-sentence input.

println!("Running inference on batch {:?}", token_ids.shape());

// Run the BERT model forward pass to generate embeddings.

let embeddings = model.forward(&token_ids, &token_type_ids, Some(&attention_mask))?;

println!("Generated embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

// Perform average pooling across tokens for each sentence embedding.

let (_n_sentence, n_tokens, _hidden_size) = embeddings.dims3()?;

let embeddings = (embeddings.sum(1)? / (n_tokens as f64))?;

let embeddings = if normalize_embeddings {

normalize_l2(&embeddings)?

} else {

embeddings

};

println!("Pooled embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

// Compute cosine similarity between all pairs of sentence embeddings.

let mut similarities = vec![];

for i in 0..n_sentences {

let e_i = embeddings.get(i)?;

for j in (i + 1)..n_sentences {

let e_j = embeddings.get(j)?;

let sum_ij = (&e_i * &e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let sum_i2 = (&e_i * &e_i)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let sum_j2 = (&e_j * &e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?;

let cosine_similarity = sum_ij / (sum_i2 * sum_j2).sqrt();

similarities.push((cosine_similarity, i, j));

}

}

// Sort and display the top 5 most similar sentence pairs.

similarities.sort_by(|u, v| v.0.total_cmp(&u.0));

for &(score, i, j) in similarities[..5].iter() {

println!("Score: {score:.2} '{}' '{}'", sentences[i], sentences[j]);

}

Ok(())

}

/// Normalizes the given tensor along the L2 norm for each row.

pub fn normalize_l2(v: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

Ok(v.broadcast_div(&v.sqr()?.sum_keepdim(1)?.sqrt()?)?)

}

The code initializes the BERT model and tokenizer by downloading the necessary configurations, weights, and tokenization files from the Hugging Face repository. Input sentences are tokenized and padded to create tensors for token IDs and attention masks, which are passed to the model for inference. The BERT model outputs dense embeddings for each sentence, which are then pooled using average pooling across token dimensions. The embeddings are optionally normalized using the L2 norm for consistency in similarity computation. Finally, the code calculates pairwise cosine similarities between sentence embeddings, ranks the results, and prints the most similar sentence pairs, showcasing the utility of the embeddings for semantic similarity tasks.

Once the basic building blocks are in place, the full BERT architecture can be constructed by stacking multiple layers of multi-head attention, feed-forward networks, and positional encodings. BERT is typically trained on tasks like masked language modeling and next sentence prediction using large corpora such as the WikiText or BookCorpus datasets. This pre-training allows BERT to learn bidirectional contextual representations, which can then be fine-tuned for various downstream tasks such as text classification, question answering, and named entity recognition.

In conclusion, the Transformer architecture marks a significant leap in deep learning, offering advantages in efficiency, scalability, and the ability to capture long-range dependencies. By leveraging self-attention mechanisms and positional encodings, Transformers can process sequences in parallel, making them highly effective for tasks involving large datasets and complex sequence relationships. Implementing Transformers in Rust using libraries like candle allows developers to explore the cutting edge of deep learning while benefiting from Rust's performance and safety guarantees.

10.2. Multi-Head Self-Attention Mechanisms

The multi-head self-attention mechanism is the cornerstone of the Transformer architecture, offering a novel way to handle sequential data, such as text or time series, by allowing the model to attend to different parts of the input sequence simultaneously. Unlike traditional models like recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, which process data sequentially, multi-head self-attention provides a mechanism to capture dependencies across the entire sequence in parallel. This capability is critical for tasks such as machine translation, language modeling, and more, where understanding both short-term and long-term dependencies is essential.

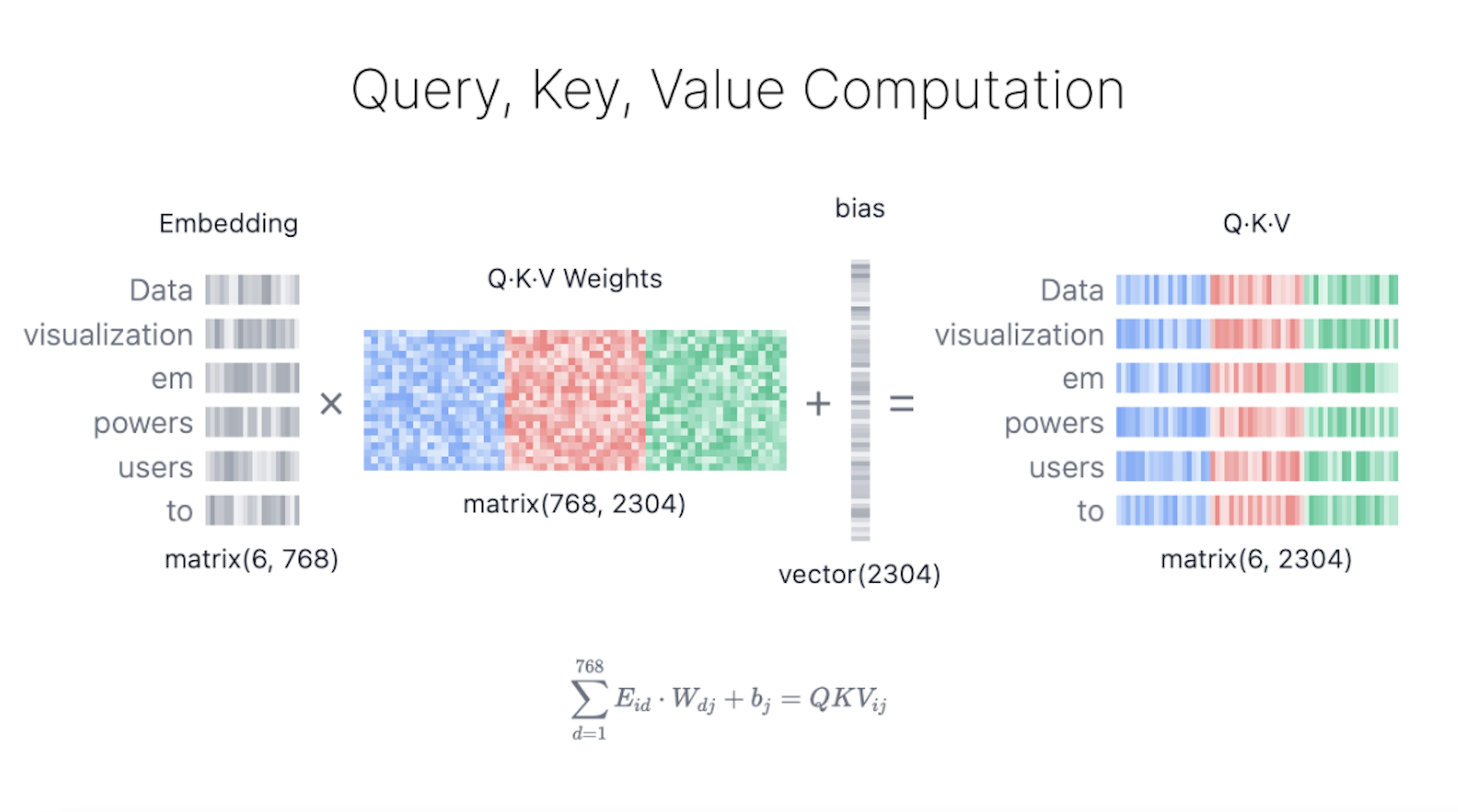

Figure 7: Computing Query, Key, and Value matrices from the original embedding.

At the heart of the multi-head self-attention mechanism is the scaled dot-product attention, a function that computes the attention scores between every pair of tokens in the input sequence. Given an input sequence of tokens $\{t_1, t_2, \dots, t_T\}$, each token is first mapped to an embedding vector. These embeddings are then transformed into three vectors for each token: the Query $Q$, Key $K$, and Value $V$. These vectors are generated through learned linear transformations:

$$Q = Z W_Q, \quad K = Z W_K, \quad V = Z W_V$$

Here, $Z \in \mathbb{R}^{T \times d}$ represents the input embeddings, where $T$ is the length of the sequence, and $d$ is the dimensionality of the embeddings. $W_Q,W_K, W_V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d_k}$ are the learned projection matrices that map the embeddings into lower-dimensional query, key, and value spaces. The parameter $d_k$ represents the dimensionality of these projections, typically chosen such that $d_k = d/h$, where $h$ is the number of attention heads.

The purpose of the query and key vectors is to compute an attention score between each pair of tokens in the sequence. This score reflects how much focus or importance token $t_i$ should give to token $t_j$. The attention score between two tokens is computed as the scaled dot product between their respective query and key vectors:

$$\text{Attention}(Q_i, K_j) = \frac{Q_i K_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}$$

The scaling factor $\frac{1}{\sqrt{d_k}}$ is applied to prevent the dot product from becoming too large, which could lead to vanishing or exploding gradients during training, particularly when the dimensionality $d_k$ is large. Without this scaling, the dot-product values could grow excessively large, and the softmax function, which will be applied next, could lead to near-zero gradients. Thus, the scaling factor stabilizes the gradient dynamics, allowing for more efficient learning.

Once the attention scores are computed, they are transformed into attention weights using the softmax function. This step ensures that the attention scores for each query token sum to one, converting raw scores into a probability distribution:

$$\alpha_{ij} = \frac{\exp\left( \frac{Q_i K_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right)}{\sum_{k=1}^{T} \exp\left( \frac{Q_i K_k^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right)}$$

Here, $\alpha_{ij}$ represents the normalized attention weight, which indicates the relevance of token $t_j$ to token $t_i$. The softmax function normalizes the attention scores across all tokens in the sequence, ensuring that the sum of the weights for any given query token equals 1. The intuition behind this normalization is to provide a mechanism by which each token distributes its "attention" over the entire sequence, focusing more on tokens that are deemed relevant based on their context and semantics.

Once the attention weights are calculated, the next step is to compute the output representation for each token. This is done by taking a weighted sum of the value vectors $V$. The value vectors contain the actual information from the input tokens, and the attention weights dictate how much each value contributes to the final output:

$$O_i = \sum_{j=1}^{T} \alpha_{ij} V_j$$

In this equation, $O_i$ is the output vector for token $t_i$, which is a weighted sum of all value vectors $V_j$, where $j$ ranges over all tokens in the sequence. The attention weights $\alpha_{ij}$ determine how much focus token $t_i$ places on token $t_j$ when constructing its output representation. Tokens that are more contextually relevant receive higher attention weights, while less relevant tokens contribute less to the final output.

The beauty of this mechanism lies in its ability to capture long-range dependencies across the sequence. For instance, in natural language processing, the attention mechanism allows the model to focus on tokens that are far apart in the sentence but are semantically connected. For example, in the sentence "The cat sat on the mat," the word "cat" might pay more attention to "mat" than to the intervening words "sat" and "on," as they are more semantically linked.

While the scaled dot-product attention mechanism is powerful, it is limited in its capacity to capture different types of relationships simultaneously. To address this, the Transformer introduces multi-head attention. Instead of using a single set of query, key, and value projections, the model computes multiple sets, known as attention heads. Each head performs independent attention calculations, learning different aspects of the input sequence.

Formally, for each head $h$, the model computes separate query, key, and value vectors:

$$Q^{(h)} = Z W_Q^{(h)}, \quad K^{(h)} = Z W_K^{(h)}, \quad V^{(h)} = Z W_V^{(h)}$$

Each head calculates its own attention weights and output vectors:

$$O_i^{(h)} = \sum_{j=1}^{T} \alpha_{ij}^{(h)} V_j^{(h)}$$

After all attention heads have computed their outputs, the results are concatenated and projected back into the original embedding space using a learned weight matrix $W_O$:

$$\text{MultiHead}(Q, K, V) = \text{Concat}(O_1^{(1)}, O_1^{(2)}, \dots, O_1^{(h)}) W_O$$

By using multiple heads, the model can attend to different parts of the sequence simultaneously, capturing a wider variety of patterns and dependencies. For example, in a machine translation task, one attention head might focus on syntactic relationships (e.g., subject-verb agreement), while another head captures semantic relationships (e.g., how the subject relates to the object across a sentence). This parallel attention mechanism allows the model to learn both local and global dependencies effectively.

From an intuitive perspective, multi-head attention can be thought of as a set of specialists, each focusing on a different aspect of the input sequence. While one head might focus on short-range dependencies, such as the immediate context of a word in a sentence, another head could focus on long-range dependencies, such as the relationship between a noun and its related verb across a clause or sentence boundary. In this way, multi-head attention allows the Transformer to simultaneously capture both fine-grained local interactions and broader global context.

This ability to focus on multiple aspects of the sequence concurrently is particularly valuable for tasks such as machine translation, where understanding the relationship between words in different parts of a sentence is crucial for generating accurate translations. In document classification tasks, different attention heads might focus on different sections of a document, enabling the model to capture both the overall structure and specific details. Similarly, in image processing, multi-head attention allows the model to focus on different regions of an image, capturing both local textures and global shapes.

In addition to enhancing the model's ability to capture diverse relationships, multi-head attention also contributes to the overall depth and capacity of the Transformer. Since each attention head operates independently, the model can learn different features at each head, and when these features are combined, the resulting representation is richer and more expressive. As the input data passes through multiple layers of multi-head attention, the model progressively refines its understanding of the sequence, allowing it to capture higher-level abstractions.

Each attention layer builds upon the previous layer's output, gradually enhancing the model's ability to understand the sequence. For example, in the first layer, attention heads might focus on basic grammatical relationships, while in later layers, the model might learn more complex semantic structures, such as cause-effect relationships or thematic connections across paragraphs. This hierarchical learning process enables the Transformer to handle tasks that require deep, multi-level reasoning, such as document summarization or question answering.

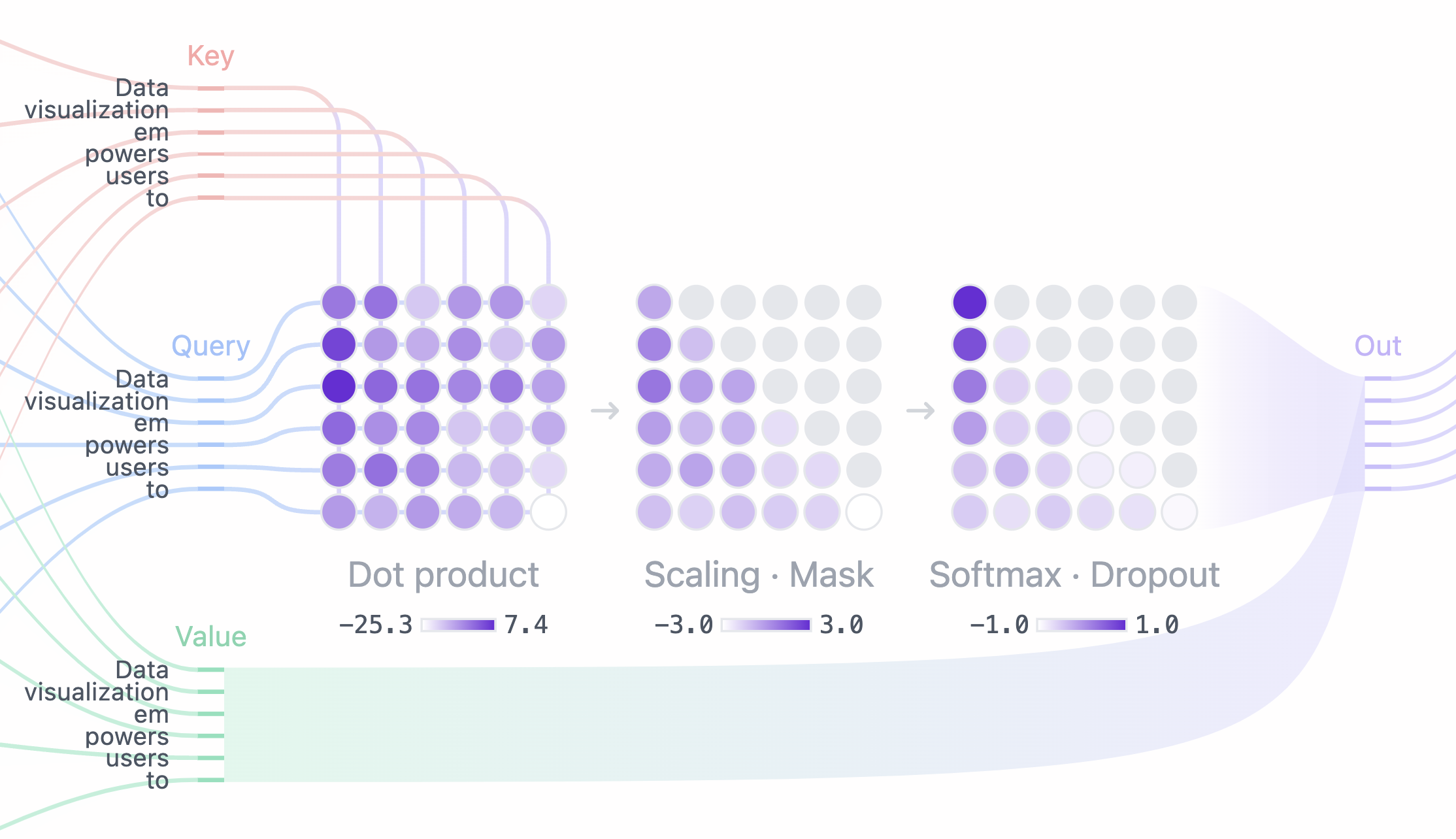

Figure 8: Using Query, Key, and Value matrices to calculate masked self-attention.

An important extension of self-attention is masked self-attention, which is crucial for tasks like language generation where the model needs to predict the next token in a sequence. In such cases, it is essential that the model does not have access to future tokens while generating a new token. This is achieved through masking in the attention mechanism.

In masked self-attention, the attention mechanism is modified by applying a mask to the attention scores. Specifically, a mask is applied to the upper triangle of the attention matrix, ensuring that tokens can only attend to previous tokens in the sequence and not future tokens. The attention scores for future tokens are set to negative infinity before applying the softmax function, effectively preventing the model from accessing them. Formally, the attention score becomes:

$$\text{MaskedAttention}(Q_i, K_j) = \begin{cases} \frac{Q_i K_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} & \text{if } j \leq i \\ -\infty & \text{if } j > i \end{cases}$$

This ensures that during generation, each token only focuses on tokens that precede it in the sequence. After applying the mask, the softmax function converts the attention scores into probabilities:

$$\alpha_{ij} = \frac{\exp\left( \frac{Q_i K_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right)}{\sum_{k=1}^{i} \exp\left( \frac{Q_i K_k^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right)}$$

By masking future tokens, the model is forced to generate each token based only on the tokens that have already been generated, thus enabling sequential generation without "peeking" ahead in the sequence. This mechanism is crucial for autoregressive tasks, such as text generation, where the model must predict each token in turn without knowledge of the future context.

From an intuitive standpoint, masked self-attention allows the model to make predictions incrementally, using only the information that has been processed so far. In tasks like language generation, this means the model can predict the next word in a sentence based on the words that have already been generated, without seeing the entire sentence at once. This is similar to how humans write, constructing sentences one word at a time based on what has already been written.

For instance, consider the task of generating a sentence like "The cat sat on the mat." After generating the first few words "The cat sat," the model must predict the next word "on" without seeing the subsequent word "mat." The masking mechanism ensures that the model generates each token in the correct order, focusing only on the past context while ignoring future tokens that have not yet been generated.

In summary, the multi-head self-attention mechanism provides the Transformer with the ability to capture complex, hierarchical relationships within input data by attending to different parts of the sequence simultaneously. By splitting the attention mechanism into multiple heads, the model can focus on diverse patterns, both local and global, enabling it to handle a wide range of tasks, from machine translation to document classification. The mathematical foundation of scaled dot-product attention, combined with the flexibility and capacity of multi-head attention, makes this mechanism one of the key innovations driving the success of the Transformer architecture. This parallel attention mechanism, which allows the model to capture nuanced relationships in the data, is what makes the Transformer so effective in modeling both long-range dependencies and fine-grained local interactions.

Masked self-attention extends this mechanism, making it possible for the model to generate sequences one token at a time, without accessing future tokens. By applying a mask to the attention scores, the model is forced to focus only on the relevant past context, enabling it to predict the next token in a sequence without “peeking” ahead. Together, these innovations form the backbone of the Transformer architecture, allowing it to handle both parallel processing of input sequences and autoregressive tasks such as language generation. This ability to capture long-range dependencies and generate coherent sequences has made the Transformer the dominant model for many tasks in natural language processing and beyond.

The T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) architecture is a unified framework for handling various NLP tasks by converting all inputs and outputs into text. It consists of an encoder-decoder structure where the encoder processes the input sequence and the decoder generates the output sequence. The encoder uses multi-head self-attention to create contextualized token embeddings, while the decoder combines self-attention, cross-attention (focusing on the encoder's output), and feed-forward layers to produce the desired text. T5 is pre-trained on a masked language modeling task, similar to BERT, but extends this by treating every NLP task, such as summarization, translation, and classification, as a sequence-to-sequence problem.

Multi-head self-attention in the T5 model is a mechanism that allows the model to focus on different parts of an input sequence simultaneously. Each attention head computes its own self-attention scores, capturing relationships between tokens in various ways. These heads work in parallel, with each head attending to different aspects of the input. The outputs from these attention heads are concatenated and passed through a linear layer to produce the final attention representation. In T5, this mechanism is crucial for both encoding and decoding processes, as it enables the model to learn contextual representations of tokens efficiently and capture long-range dependencies in the input sequence.

This code demonstrates the use of the T5 model's encoder to compute embeddings for a set of input sentences. It loads the T5-small model configuration, weights, and tokenizer from the Hugging Face repository and processes a list of hardcoded sentences to generate embeddings. By leveraging the pre-trained T5 encoder, the code extracts semantic representations for each sentence and computes cosine similarities to measure the semantic closeness between different sentences.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

candle-core = "0.8.0"

candle-examples = "0.8.0"

candle-nn = "0.8.0"

candle-transformers = "0.8.0"

clap = { version = "4", features = ["derive"] }

hf-hub = "0.3.2"

image = "0.25.5"

tokenizers = "0.20.3"

use candle_transformers::models::t5;

use anyhow::{Error as E, Result};

use candle_core::{DType, Device, Tensor};

use candle_nn::VarBuilder;

use hf_hub::{api::sync::Api, Repo, RepoType};

use tokenizers::Tokenizer;

// Define the data type to be used (e.g., 32-bit floating point).

const DTYPE: DType = DType::F32;

// Struct to manage the T5 model components, including device configuration, model configuration, and weights.

struct T5ModelBuilder {

device: Device, // The computation device (e.g., GPU or CPU).

config: t5::Config, // T5 model configuration.

weights_filename: Vec<std::path::PathBuf>, // Paths to the model weights files.

}

impl T5ModelBuilder {

// Load the T5 model and tokenizer.

pub fn load() -> Result<(Self, Tokenizer)> {

// Use GPU 0 if available, otherwise fallback to CPU.

let device = Device::cuda_if_available(0)?;

// Hardcoded T5 model identifier and revision from Hugging Face Hub.

let model_id = "t5-small".to_string();

let revision = "refs/pr/15".to_string();

// Fetch model files from Hugging Face Hub.

let repo = Repo::with_revision(model_id.clone(), RepoType::Model, revision);

let api = Api::new()?;

let repo = api.repo(repo);

let config_filename = repo.get("config.json")?; // Configuration file for T5.

let tokenizer_filename = repo.get("tokenizer.json")?; // Tokenizer file for T5.

let weights_filename = vec![repo.get("model.safetensors")?]; // Model weights in safetensors format.

// Load the model configuration and tokenizer.

let config = std::fs::read_to_string(config_filename)?;

let mut config: t5::Config = serde_json::from_str(&config)?;

config.use_cache = true; // Enable caching for faster performance.

let tokenizer = Tokenizer::from_file(tokenizer_filename).map_err(E::msg)?;

Ok((

Self {

device,

config,

weights_filename,

},

tokenizer,

))

}

// Build the T5 encoder model from the weights and configuration.

pub fn build_encoder(&self) -> Result<t5::T5EncoderModel> {

let vb = unsafe {

VarBuilder::from_mmaped_safetensors(&self.weights_filename, DTYPE, &self.device)?

};

Ok(t5::T5EncoderModel::load(vb, &self.config)?)

}

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

// Define a set of example sentences to process.

let sentences = [

"The cat sits outside",

"A man is playing guitar",

"I love pasta",

"The new movie is awesome",

"The cat plays in the garden",

"A woman watches TV",

"The new movie is so great",

"Do you like pizza?",

];

let normalize_embeddings = true; // Whether to normalize embeddings for better similarity computation.

// Load the T5 model and tokenizer.

let (builder, tokenizer) = T5ModelBuilder::load()?;

let mut model = builder.build_encoder()?; // Build the T5 encoder model.

// Process each sentence to generate embeddings.

let mut all_embeddings = Vec::with_capacity(sentences.len());

for sentence in sentences {

// Tokenize the sentence and convert tokens to a tensor.

let tokens = tokenizer

.encode(sentence, true)

.map_err(E::msg)?

.get_ids()

.to_vec();

let token_ids = Tensor::new(&tokens[..], &builder.device)?.unsqueeze(0)?; // Convert tokens to a tensor.

let embeddings = model.forward(&token_ids)?; // Generate embeddings using the T5 encoder.

println!("Generated embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

// Perform average pooling to get sentence-level embeddings.

let (_n_sentence, n_tokens, _hidden_size) = embeddings.dims3()?;

let embeddings = (embeddings.sum(1)? / (n_tokens as f64))?; // Average over tokens.

let embeddings = if normalize_embeddings {

normalize_l2(&embeddings)? // Normalize embeddings to unit length.

} else {

embeddings

};

println!("Pooled embeddings {:?}", embeddings.shape());

all_embeddings.push(embeddings)

}

// Compute cosine similarities between sentence embeddings.

let mut similarities = vec![];

for (i, e_i) in all_embeddings.iter().enumerate() {

for (j, e_j) in all_embeddings

.iter()

.enumerate()

.skip(i + 1)

{

let sum_ij = (e_i * e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?; // Dot product between embeddings.

let sum_i2 = (e_i * e_i)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?; // Norm of embedding i.

let sum_j2 = (e_j * e_j)?.sum_all()?.to_scalar::<f32>()?; // Norm of embedding j.

let cosine_similarity = sum_ij / (sum_i2 * sum_j2).sqrt(); // Compute cosine similarity.

similarities.push((cosine_similarity, i, j))

}

}

// Sort and display the top 5 most similar sentence pairs.

similarities.sort_by(|u, v| v.0.total_cmp(&u.0));

for &(score, i, j) in similarities[..5].iter() {

println!("Score: {score:.2} '{}' '{}'", sentences[i], sentences[j]);

}

Ok(())

}

// Normalize tensor values to unit length using L2 normalization.

pub fn normalize_l2(v: &Tensor) -> Result<Tensor> {

Ok(v.broadcast_div(&v.sqr()?.sum_keepdim(1)?.sqrt()?)?)

}

The code begins by downloading the WikiText-2 dataset and extracting it using the reqwest and zip crates. A Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer is then trained on the dataset using the tokenizers crate, with the resulting tokenizer saved as tokenizer.json. The TransformerModel struct defines the model's encoder-The code first initializes the T5 model and tokenizer by downloading the required files from the Hugging Face repository. It then processes a list of sentences by tokenizing them, converting them into tensors, and passing them through the T5 encoder to generate embeddings. The embeddings are pooled using average pooling to create fixed-length vectors for each sentence. Afterward, the code calculates cosine similarities between these sentence embeddings to determine how semantically similar the sentences are. Finally, it sorts and displays the top five most similar sentence pairs based on the computed similarity scores. This workflow showcases the capability of the T5 encoder to create meaningful sentence embeddings for downstream tasks.

Once implemented, multi-head attention can be used as a building block in a Transformer model. By experimenting with different numbers of attention heads and layers, developers can optimize the performance of the model for various tasks, such as document classification, machine translation, or time series forecasting. For example, increasing the number of attention heads allows the model to capture more diverse relationships in the data, but it also increases the computational cost.

In conclusion, multi-head self-attention is a fundamental mechanism in the Transformer architecture that allows models to capture complex relationships within sequences by attending to different parts of the input simultaneously. By leveraging multiple attention heads, Transformers can model both local and global dependencies, making them highly effective for a wide range of tasks. Implementing multi-head attention in Rust using libraries like tch-rs allows developers to explore state-of-the-art deep learning techniques while benefiting from Rust's performance and safety features.

10.3. Positional Encoding and Sequence Order

In Transformer models, one of the fundamental challenges arises from their reliance on self-attention mechanisms, which process input sequences in parallel. Unlike Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) that naturally capture sequence order by processing inputs one step at a time, the self-attention mechanism treats all tokens equally and simultaneously. This characteristic of Transformers, while enabling parallelism and computational efficiency, results in a lack of inherent sequence order awareness. Since many tasks in natural language processing, time series prediction, and other sequential domains require the model to understand the order of tokens, the introduction of positional encoding is necessary to differentiate between tokens based on their position within a sequence. Positional encoding allows the Transformer to capture both local and global patterns while preserving the order of the sequence, which is essential for tasks like machine translation, text generation, and speech recognition.

The most common approach to positional encoding in Transformers is based on sinusoidal functions, a continuous and deterministic method that encodes the position of each token in the sequence. The advantage of using sinusoidal functions is that the encoding is smooth, continuous, and periodic, making it well-suited to capture relationships between tokens, even for long sequences. Formally, given a sequence of length $T$ and an embedding dimension $d$, the positional encoding for each token at position $\text{pos}$ and dimension index $i$ within the embedding is computed using the following functions:

$$PE_{\text{pos}, 2i} = \sin\left(\frac{\text{pos}}{10000^{\frac{2i}{d}}}\right)$$

$$PE_{\text{pos}, 2i+1} = \cos\left(\frac{\text{pos}}{10000^{\frac{2i}{d}}}\right)$$

In these equations, $\text{pos}$ represents the position of the token in the sequence, and $i$ indexes the embedding dimension. The sine function is used for even indices of the embedding, while the cosine function is used for odd indices. The rationale for using these two distinct functions is that they provide different but complementary ways of encoding positional information, ensuring that the positional encoding is unique for each position in the sequence.

The denominator $10000^{\frac{2i}{d}}$ ensures that the frequencies of the sine and cosine waves decrease as the dimension index increases. This introduces a notion of scale in the positional encoding, with lower dimensions capturing coarse-grained information about token positions and higher dimensions capturing fine-grained details. As a result, the Transformer can capture both short-range and long-range dependencies, depending on the embedding dimension being used.

Once these positional encodings are computed, they are added element-wise to the token embeddings. The final input to the Transformer becomes the sum of the content-based embedding (which captures the meaning of the token) and the positional encoding (which captures the position of the token in the sequence):

$$\mathbf{Z} = \mathbf{E} + \mathbf{PE}$$

Here, $\mathbf{E}$ represents the matrix of token embeddings, and $\mathbf{PE}$ is the matrix of positional encodings. This combination allows the model to take into account both the semantic content of the tokens and their order within the sequence.

The approach described above is known as absolute positional encoding, where each position in the sequence is assigned a unique encoding based on its absolute position from the start of the sequence. This method works well for tasks where the position of each token relative to the beginning of the sequence is important. For example, in machine translation, the order of words is crucial for producing accurate translations, as grammatical structures like subject-verb agreement or prepositional phrases depend on word order.

The sinusoidal nature of absolute positional encoding has several advantages. First, the periodicity of sine and cosine functions allows the model to generalize well to sequences of different lengths. Even if the Transformer encounters a sequence longer than any seen during training, the periodicity of the positional encodings enables the model to infer relationships between tokens based on their position. Second, because the encoding is deterministic, it does not introduce any additional learnable parameters, making it computationally efficient.

However, absolute positional encoding may not perform optimally in tasks where the relative positions between tokens are more important than their absolute positions. For example, in time series analysis, the key information might lie in the difference between two time points, rather than in their absolute positions within the series. In such cases, relative positional encoding offers a more flexible alternative.

In relative positional encoding, the focus shifts from the absolute positions of tokens to the relative distances between them. Instead of assigning a fixed positional encoding to each token, the model computes the relative distances between tokens, capturing local dependencies more effectively. This approach is particularly useful in tasks where the relationship between tokens depends on their proximity rather than their position from the start of the sequence.

Mathematically, the attention score between two tokens $t_i$ and $t_j$ in relative positional encoding is modified by introducing a bias term that depends on the relative distance between the two tokens:

$$a_{i,j} = \frac{Q_i \cdot K_j^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} + b(i - j)$$

Here, $a_{i,j}$ is the attention score between token $t_i$ and token $t_j$, $Q_i$ and $K_j$ are the query and key vectors for tokens $i$ and $j$, and $b(i - j)$ is a learnable bias term that depends on the relative distance $i - j$ between the two tokens. This term allows the model to adjust the attention score based on how far apart the tokens are, providing the model with a way to account for local context in the sequence.

Relative positional encoding offers several advantages over the absolute method. By focusing on the distances between tokens, it is better suited for tasks where local patterns or temporal relationships are more important. For instance, in music generation, the relationship between consecutive notes is more important than their absolute position in the sequence. Similarly, in time series forecasting, the difference between time steps may carry more information than the absolute time stamps.

From a conceptual standpoint, positional encoding plays a crucial role in enabling Transformer models to handle sequences of varying lengths and structures. In natural language processing tasks like translation or text generation, where the order of words is critical, positional encoding ensures that the model can differentiate between tokens based on their position. This allows the Transformer to understand grammatical structures, such as subject-verb agreement or word order in different languages, and to generate coherent text.

In tasks like time series prediction, positional encoding enables the model to recognize patterns over time, even when the sequences have different lengths or irregularly spaced intervals. Absolute positional encoding is effective for tasks where the position of each token relative to the start of the sequence matters, such as in language modeling or speech recognition. On the other hand, relative positional encoding excels in tasks where the relationship between tokens is more dependent on their proximity, such as in music generation or certain time series tasks.

The choice between absolute and relative positional encoding often depends on the task's specific requirements. Absolute positional encoding is computationally efficient because it is deterministic and does not require any additional learnable parameters. It works well for tasks where the sequence length is fixed, or where the absolute positions of tokens are critical for understanding the task. However, it may not generalize as well to sequences of different lengths, and it may struggle in tasks where relative distances between tokens are more important than their absolute positions.

Relative positional encoding, while more flexible, introduces additional computational complexity. The learnable bias terms $b(i - j)$ increase the number of parameters the model must learn, which can lead to longer training times and higher memory usage. However, this added complexity is often worth it for tasks that require the model to focus on relative distances between tokens, such as in time series analysis or music generation, where patterns may shift or repeat over time.

Positional encoding is an essential feature of Transformer models, addressing their inherent inability to recognize sequence order by embedding positional information into the token representations. This mechanism ensures the model can capture both local and global patterns while preserving the sequential structure of the input. Absolute positional encoding, often implemented using sinusoidal functions, is computationally efficient and well-suited for fixed-length sequences. In contrast, relative positional encoding, which uses learnable bias terms, offers greater adaptability for tasks where token relationships are determined more by relative proximity than absolute position. The choice between these methods depends on the specific task and input data, with each offering unique advantages in different scenarios.

The Longformer architecture introduces a refined approach to positional embeddings, tailored to its efficient long-range attention mechanism. Unlike traditional Transformers that rely on full self-attention, Longformer employs a combination of local windowed attention and sparse global attention to manage longer sequences without overwhelming computational costs. To preserve sequence order and maintain token position awareness within this attention structure, Longformer incorporates learnable absolute positional embeddings. These embeddings are specifically aligned with the model's attention patterns, enabling it to effectively capture positional information across both local and global contexts. This integration is vital for preserving relational coherence, ensuring that sparse attention mechanisms do not compromise the model’s ability to interpret dependencies between distant or nearby tokens. By leveraging these embeddings, Longformer achieves an optimal balance between computational efficiency and the capacity to model long-range dependencies, making it particularly effective for tasks such as document classification and question answering on lengthy text inputs.

This Rust code demonstrates the implementation of a Longformer-based text processor. It uses the rust-bert library for the Longformer model, rust_tokenizers for tokenization, and tch for Tensor manipulation and neural network operations. The script initializes the Longformer model with specific configurations for efficient long-range attention, downloads tokenizer files if needed, and processes input text to generate hidden state outputs from the model. The code highlights attention mechanisms, including local and global attention windows, to balance computational efficiency and long-range dependency modeling. It also includes functionality for tokenizing text, creating attention masks, and handling model inference.

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

tch = "0.8"

reqwest = { version = "0.11", features = ["blocking"] }

flate2 = "1.0"

tokio = { version = "1", features = ["full"] }

rust-bert = "0.19.0"

rust_tokenizers = "8.1.1"

use anyhow::{Result, anyhow};

use reqwest::Url;

use std::{fs, path::Path};

use tch::{nn, Device, Tensor};

use rust_bert::longformer::{LongformerConfig, LongformerModel};

use rust_tokenizers::tokenizer::{RobertaTokenizer, Tokenizer};

use std::io::Write;

// Constants for attention windows

const LOCAL_WINDOW_SIZE: i64 = 512;

const GLOBAL_WINDOW_SIZE: i64 = 32;

// URLs to download the tokenizer files

const VOCAB_URL: &str = "https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/vocab.json";

const MERGES_URL: &str = "https://huggingface.co/roberta-base/resolve/main/merges.txt";

// Function to download a file

async fn download_file(url: &str, filepath: &Path) -> Result<(), anyhow::Error> {

if filepath.exists() {

println!("File {} already exists. Skipping download.", filepath.display());

return Ok(());

}

println!("Downloading {} to {}...", url, filepath.display());

let response = reqwest::get(Url::parse(url)?).await?;

let mut file = fs::File::create(filepath)?;

let content = response.bytes().await?;

file.write_all(&content)?;

println!("Downloaded {}", filepath.display());

Ok(())

}

struct LongformerProcessor {

model: LongformerModel,

tokenizer: RobertaTokenizer,

device: Device,

}

impl LongformerProcessor {

pub fn new(_model_path: &Path, vocab_path: &Path, merges_path: &Path) -> Result<Self, anyhow::Error> {

let device = Device::cuda_if_available();

let vs = nn::VarStore::new(device);

// Initialize config with correct attention window sizes for each layer

let mut config = LongformerConfig::default();

let num_hidden_layers = config.num_hidden_layers as usize; // Get the number of layers

config.attention_window = vec![LOCAL_WINDOW_SIZE; num_hidden_layers]; // Set attention window for all layers

config.max_position_embeddings = 4096;

config.pad_token_id = Some(1);

config.sep_token_id = 2; // This is i64, not Option<i64>

config.type_vocab_size = 1;

config.output_hidden_states = Some(true); // Request hidden states

// Initialize model

let model = LongformerModel::new(&vs.root(), &config, false);

let tokenizer = RobertaTokenizer::from_file(

vocab_path,

merges_path,

true, // lowercase

false, // strip_accents

).map_err(|e| anyhow!("Failed to load RoBERTa tokenizer: {}", e))?;

Ok(Self {

model,

tokenizer,

device,

})

}

fn create_sparse_attention_mask(&self, seq_length: i64) -> Result<Tensor, anyhow::Error> {

let options = (tch::Kind::Int64, self.device);

let attention_mask = Tensor::zeros(&[1, seq_length], options);

// Set local attention windows

for i in 0..seq_length {

// Fill with 1 for local attention

let _ = attention_mask.narrow(1, i, 1).fill_(1);

// Mark global attention tokens

if i < GLOBAL_WINDOW_SIZE {

let _ = attention_mask.narrow(1, i, 1).fill_(2);

}

}

Ok(attention_mask)

}

pub fn process_text(&self, input_text: &str, max_length: usize) -> Result<Vec<Tensor>, anyhow::Error> {

// Tokenize input

let encoding = self.tokenizer.encode(

input_text,

None,

max_length,

&rust_tokenizers::tokenizer::TruncationStrategy::LongestFirst,

0,

);

let input_ids: Vec<i64> = encoding.token_ids.iter()

.map(|&id| id as i64)

.collect();

// Create input tensor

let input_tensor = Tensor::of_slice(&input_ids)

.to_kind(tch::Kind::Int64)

.to_device(self.device)

.unsqueeze(0);

// Create attention mask

let attention_mask = self.create_sparse_attention_mask(input_ids.len() as i64)?;

// Global attention mask (1 for global tokens, 0 for local attention)

let global_attention_mask = attention_mask.eq(2).to_kind(tch::Kind::Int64);

// Forward pass with proper error handling

let output = if let Ok(o) = self.model.forward_t(

Some(&input_tensor),

Some(&attention_mask),

Some(&global_attention_mask),

None, // token_type_ids

None, // position_ids

None, // inputs_embeds

false, // output_attentions

) {

o

} else {

return Err(anyhow!("Failed to perform forward pass"));

};

// Ensure we get hidden states

if let Some(hidden_states) = output.all_hidden_states {

Ok(hidden_states)

} else {

Err(anyhow!("Hidden states were not returned"))

}

}

}

// Main function

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), anyhow::Error> {

// Define the directory where the tokenizer files will be stored

let tokenizer_dir = Path::new("./tokenizer_files");

// Create the directory if it doesn't exist

if !tokenizer_dir.exists() {

println!("Creating directory: {}", tokenizer_dir.display());

fs::create_dir_all(tokenizer_dir)?;

}

// Initialize paths

let vocab_path = tokenizer_dir.join("vocab.json");

let merges_path = tokenizer_dir.join("merges.txt");

// Ensure the tokenizer files exist by downloading them if necessary

download_file(VOCAB_URL, &vocab_path).await?;

download_file(MERGES_URL, &merges_path).await?;

// Replace with your actual model path if needed

let model_path = Path::new("path/to/model");

// Initialize processor

let processor = LongformerProcessor::new(model_path, &vocab_path, &merges_path)?;

// Sample input

let input_text = "This is a sample long input sequence...";

// Process text

let outputs = processor.process_text(input_text, 4096)?;

// Print details of outputs

println!("Number of layers in outputs: {}", outputs.len());

for (i, output) in outputs.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Layer {} output shape: {:?}", i, output.size());

// Print some sample values from the tensor (e.g., first 5 values)

let first_five_values = output

.narrow(1, 0, 5) // Get the first 5 tokens

.narrow(2, 0, 5) // Get the first 5 hidden states (dimensions may vary)

.to_kind(tch::Kind::Float)

.print();

println!("Layer {} sample output values: {:?}", i, first_five_values);

}

Ok(())

}

This Rust code implements a Longformer-based text processor capable of handling long input sequences efficiently. It initializes a Longformer model with a configuration tailored for sparse attention, using local windowed attention for most tokens and global attention for a few important ones. The code downloads and sets up tokenizer files (vocab.json and merges.txt) for the RoBERTa tokenizer, which is compatible with the Longformer. Input text is tokenized into IDs, converted into tensors, and paired with a sparse attention mask that differentiates between local and global attention tokens. The positional embeddings, defined by max_position_embeddings in the configuration, ensure the model maintains the order of tokens across long sequences. The sparse attention mechanism, guided by the attention mask, reduces computational costs while retaining the ability to model long-range dependencies. The processed text is passed through the model, generating hidden states for each layer, which are then printed and analyzed for their shape and values. This setup enables efficient text processing for tasks requiring long-context understanding, such as document classification and summarization.

For tasks requiring relative positional encoding, additional bias terms are learned to represent the relative distances between tokens. This can be implemented by modifying the attention mechanism to include the relative distance bias during the computation of attention scores.

Once positional encoding is implemented, it can be integrated into a Transformer model and applied to tasks such as time series prediction or text generation. By experimenting with different positional encoding strategies (absolute vs. relative), developers can optimize the model for tasks that require varying levels of flexibility and sequence length generalization.

In conclusion, positional encoding is a crucial component of Transformer models, ensuring that self-attention mechanisms retain sequence order information. The use of sinusoidal functions in absolute encoding allows the model to process sequences of varying lengths, while relative positional encoding introduces additional flexibility by focusing on the distances between tokens. The choice between absolute and relative encoding depends on the task at hand and the complexity of the data, with relative encoding being particularly useful for tasks requiring localized patterns and varying sequence lengths. Implementing positional encoding in Rust using libraries like tch-rs allows developers to build robust, flexible models that can handle a wide range of sequence-based tasks effectively.

10.4. Feed-Forward Networks and Layer Normalization

In the Transformer architecture, each block is composed of not only the self-attention mechanism but also feed-forward networks (FFNs) and layer normalization. These components enhance the model's ability to learn complex representations and ensure stable training, especially in deep architectures. The feed-forward neural networks contribute non-linearity and depth to the model, helping it capture more abstract patterns, while layer normalization plays a crucial role in maintaining gradient stability. This combination enables the Transformer to learn effectively across both local and global contexts, a key factor in its success for tasks like machine translation, text generation, and question answering.

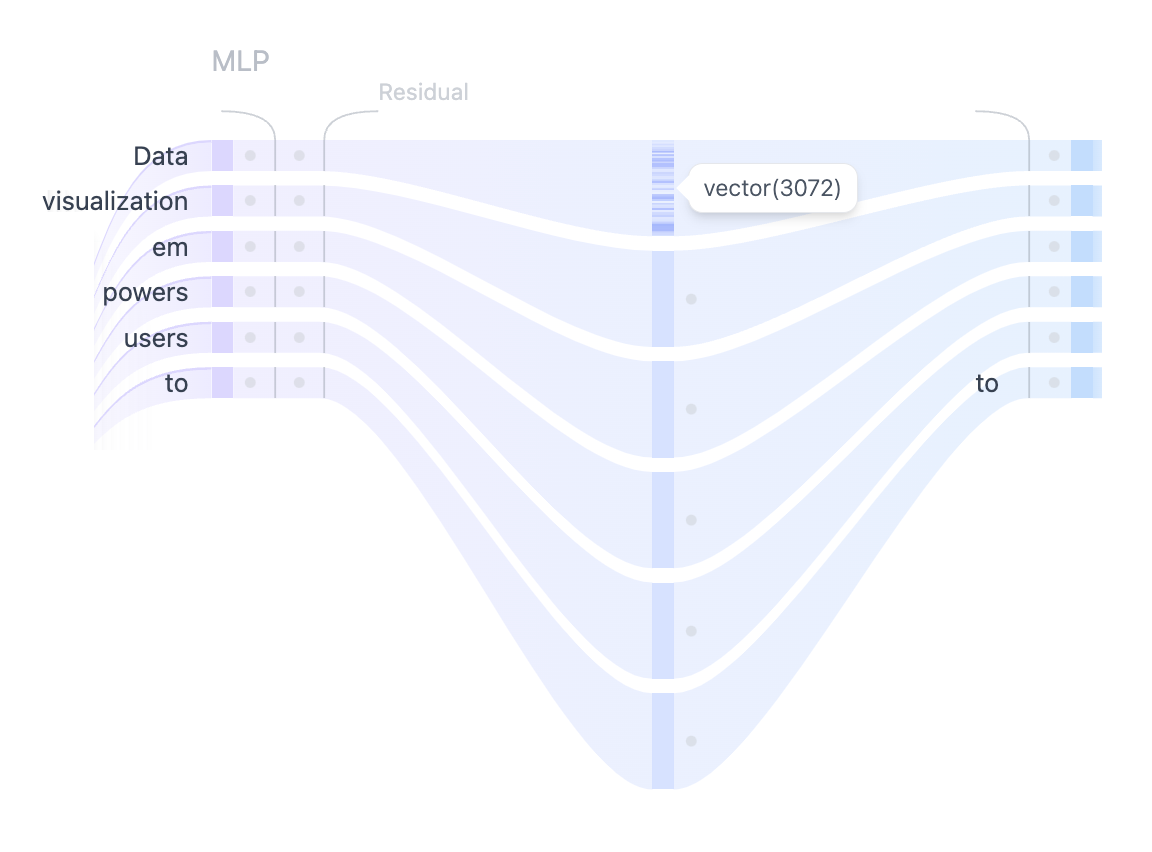

Figure 9: Using the MLP layer to project the self-attention representations into higher dimensions to enhance the model's representational capacity.

After the multi-head self-attention mechanism, the outputs for each token are passed through a feed-forward neural network or multi-layer perceptron (MLP). The MLP consists of two linear transformations with a non-linear activation function between them. Mathematically, given an input vector $X$, the feed-forward operation in a Transformer is defined as:

$$\text{MLP}(X) = \text{GELU}(X W_1 + b_1) W_2 + b_2$$

In this formulation, $W_1 \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times 4d}$ and $W_2 \in \mathbb{R}^{4d \times d}$ are learned weight matrices, where $d$ is the dimensionality of the input representation, and $4d$ is the expanded dimensionality in the hidden layer. The biases $b_1$ and $b_2$ are vectors of appropriate sizes. The activation function GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) introduces non-linearity, allowing the model to capture more complex relationships in the data.

The two linear transformations and the GELU activation function work together to introduce flexibility in learning. The first linear transformation projects the input from dimension $d$ to a higher dimensional space $4d$, providing a richer, more expressive intermediate representation. The non-linearity introduced by GELU allows the network to model non-trivial mappings between input and output. Finally, the second linear transformation maps the expanded representation back to the original dimensionality $d$, ensuring consistency with the inputs to other parts of the model.

More formally, the feed-forward network can be viewed as a composition of two affine transformations and an activation function:

$$\text{FFN}(X) = W_2 (\sigma(W_1 X + b_1)) + b_2$$

Here, $X \in \mathbb{R}^{d}$ is the input vector, $W_1 \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times 4d}$ and $W_2 \in \mathbb{R}^{4d \times d}$ are the weight matrices, and $b_1 \in \mathbb{R}^{4d}$ and $b_2 \in \mathbb{R}^{d}$ are the bias terms. The function $\sigma$ represents a non-linear activation function, such as ReLU or GELU. This non-linearity is critical for the network's ability to approximate complex functions and learn hierarchical features.

The function GELU, which has become a common choice in Transformer-based models, such as BERT, is smoother than the more commonly used ReLU. Mathematically, the GELU function is defined as:

$$\text{GELU}(x) = 0.5x \left(1 + \text{erf}\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right)$$

where $\text{erf}(x)$ is the error function. Unlike ReLU, which is a piecewise linear function, GELU introduces smoothness into the activation, which improves the gradient flow and enhances learning, especially for large-scale models.

While the self-attention mechanism captures global relationships across tokens in a sequence, the feed-forward network operates independently on each token's representation. It acts element-wise across the sequence, meaning that every token’s representation is passed through the same feed-forward layers without interacting with other tokens at this stage. This independence allows the network to refine each token’s representation individually, adding depth to the model and enabling it to learn hierarchical and more abstract features. This ability to process each token independently complements the attention mechanism’s global context, allowing the Transformer to capture both fine-grained and high-level patterns.

The increase in dimensionality from $d$ to $4d$ in the first layer and the subsequent reduction back to $d$ in the second layer enables the model to learn richer intermediate representations, making the Transformer highly effective for a variety of tasks. Without the feed-forward networks, the model's capacity to learn complex, non-linear relationships would be severely limited, as self-attention alone does not introduce sufficient non-linearity.

In deep Transformer architectures, stabilizing the training process is essential, as the model is prone to issues such as vanishing or exploding gradients. Layer normalization is introduced to address these problems and to ensure that the model can train efficiently, even with many layers.

Layer normalization normalizes the input across the feature dimensions for each token in the sequence. Given an input $X$, layer normalization transforms it as follows:

$$\hat{X} = \frac{X - \mu}{\sqrt{\sigma^2 + \epsilon}} \cdot \gamma + \beta$$

Here, $\mu$ and $\sigma^2$ are the mean and variance of the input computed across the features, $\gamma$ and $\beta$ are learned scale and shift parameters, and $\epsilon$ is a small constant added for numerical stability. The purpose of layer normalization is to ensure that the inputs to each layer have a mean of zero and a variance of one, which prevents instability in the gradient updates and improves the model’s convergence.